Taxing the Tech Giants – Why Canada Should Not Follow the French Example

Research Paper showing that the tech giants pay substantial taxes, and that a tax on revenues will likely be paid by Canadian consumers and businesses

During the last federal election campaign, all parties promised to raise taxes on the digital giants. Although this is on ice awaiting the conclusion of OECD discussions on the matter, the idea is still present in the public debate, and may end up being adopted one way or another. This publication shows, however, that the so-called GAFA companies have been taxed at a level similar to or higher than large Canadian corporations, and that it will be consumers and the Canadian economy in general that would pay for such a measure.

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| Why overtaxing Big Tech is such a bad idea (National Post, January 22, 2020)

Le piège de la taxation numérique (Le Devoir, January 22, 2020) |

Interview (in French) with Gaël Campan (Dutrizac, QUB Radio, January 22, 2020)

Interview with Peter St. Onge (Danielle Smith Show, Global, January 22, 2020) |

Interview with Peter St. Onge (Bloomberg Markets, BNN, January 22, 2020) |

This Research Paper was prepared by Nicolas Marques and Peter St. Onge, with the collaboration of Gaël Campan. Mr. Marques is an Associate Researcher at the MEI, Mr. St. Onge and Mr. Campan are Senior Economists at the MEI.

Highlights

During the 2019 election campaign, the Liberal Party had promised to introduce a 3% tax on the revenues of the Web giants earned in Canada. The revenues concerned are those from targeted advertising and digital intermediation (market place) services, earned by companies with annual global revenues of over $1 billion, and over $40 million in Canada, including Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Apple (the “GAFA”). Even if Ottawa recently said it wanted to wait for the completion of the OECD’s work, the approach considered by the federal government deserves to be examined in depth.

Our detailed analysis shows that these tech giants already pay taxes at rates equal or higher than the average large Canadian company. Moreover, the French experience confirms that this tax will likely be paid by Canadian consumers and Canadian businesses, which poses risks to competition and consumer choice.

Chapter 1 – France’s Bad Example

- In France, the introduction of a specific tax on Big Tech companies has been presented to the public as “a matter of justice.” Unable to determine exact profits in a given country, the solution consisted of taxing these companies’ revenues in each country.

- Adopted in July 2019, the French tax applies to revenues from advertising, revenues from intermediation fees realized by marketplaces, and the resale of users’ personal data for advertising purposes. It affects companies with at least €750 million in worldwide revenues and at least €25 million in revenues in France, and applies at the rate of 3% of the revenues.

Chapter 2 – Tax Treatment of the Tech Giants

- We sometimes hear that the Web giants collective-ly known as the GAFA benefit overall from more

favourable tax treatment than big Canadian companies. - Analysis of the annual results of the GAFA companies rather shows that far from escaping taxation, they are taxed significantly, with a 24% average tax rate on their profits over five-year and ten-year periods.

- The analysis of the effective tax rates on the earnings of large Canadian companies shows that the average GAFA tax rate is similar or higher. The tax advantage supposedly enjoyed by the GAFA companies is not supported by the facts. The figures even show that it is Canadian companies and the Canadian economy that were favoured in comparison to U.S. companies in the recent past.

- Things changed radically, however, following the reforms implemented by the Trump administration. The issue for Canada is not to implement a tax rate offsetting an alleged tax advantage; rather, the issue lies in the ability to preserve the competitiveness of its economy following the tax cuts established by its neighbour.

- Multiple studies have indicated the negative impact that the corporate income tax can have on economic growth.

Chapter 3 – An Additional 3% Tax Is Not Trivial

- An additional tax on revenues is likely to have adverse effects, according to a logical sequence well-documented by economists and tax specialists.

- Unlike the income tax, which is actually collected on their profits, taxes on revenues are calculated on all of a company’s activities, whether or not these are profitable. This type of tax may therefore make a company unprofitable. Taxes on revenues are among those most strongly criticized by economists.

- The gain in public receipts from the application of the tax on revenues is thus likely to be partially offset by the decline in corporate income tax receipts. Even so, the tax burden on companies is increased, and their profitability reduced.

- The gain for public finances may be diminished further if companies abandon a market where revenues are taxed in favour of more profitable markets. Added to this is the impact on employment, wages, and the economy as a whole.

- The global profit margin of a player such as Amazon over the past ten years is 2.5%, less than the planned 3% tax rate.

- If the tax on digital services had been applied to all the activities of the TSX 60 companies over the past ten years, it would have completely wiped out the profits of nearly one-quarter (22%) of them.

Chapter 4 – A Tax That Will Hurt Canadian Businesses and Consumers

- The digital tax is likely to penalize the Canadian digital ecosystem and Canadian business in general, as well as consumers. The Canadian tax cannot target U.S. companies unilaterally. Such an approach would be deemed discriminatory and could expose Canada to sanctions.

- In France, the levying of a 3% tax on revenues could reduce the profit of a company to zero or even push it into the red. This is hardly likely to encourage the development of lower-margin activities, as is often the case for start-ups active in the digital sector.

- The tax will pose the same problems in Canada. A recent federal government report noted that in 2016, thirteen Canadian companies active in the digital sector had annual revenues exceeding $1 billion, while 46 others reported revenues of between $500 million and $1 billion. These companies could potentially be subject to the tax and could see their profitability diminished or wiped out.

- Economic theory and history have shown that taxes are rarely paid by those we believe are being taxed or whom we would like to tax. Usually, it is the party at the end of the chain, namely the consumer, who bears the burden.

- Major global players—notably the GAFA companies—are able to pass on most of the cost of the digital tax to their customers, their business partners, or both. According to a recent estimate, more than half (55%) of the total burden arising from the new French tax will be borne by consumers, 40% by companies using digital platforms, and only 5% by Big Tech firms.

- On October 1st, 2019, Amazon raised its commissions in order to offset the extra cost arising from the French digital tax. American companies can thus be expected to adjust their services and prices in response to the prospective Canadian tax.

- Some digital companies will find it difficult to pass on the impact of the tax to their business partners or consumers. By putting Canadian players that have yet to achieve critical mass in a weaker position, the tax could favour the existing large American companies.

- By complicating the economic equation for traditional companies that seek to turn themselves into digital players, the tax could help maintain the gap between traditional and digital businesses, penalizing our economies once again.

Chapter 5 – International Risks to Trade and Public Finances

- Despite precautions taken by the French authorities, U.S. authorities have initiated proceedings under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974.

- After the World Trade Organization (WTO) authorized the United States to impose sanctions on the European Union, the country targeted France and French wine in particular. The United States also threatened the imposition of tariffs of up to 100% on French imports like champagne, cheese, yogurt, and cosmetics.

- The French experience is likely to speed up and add credibility to the rewriting of international tax rules under OECD leadership. This possibility should not be taken lightly. For example, in France, the gains from taxing digital companies will probably be partially offset by a decrease in tax receipts from large French groups that have a foreign presence.

- Canada’s federal government would do well to come up with a precise assessment of whether the additional receipts from taxing the revenues of foreign companies operating in Canada will offset the reduction in receipts from Canadian companies operating in the rest of the world.

Despite the phenomenal success of the GAFA companies, we should keep in mind that they have followed the tax rules that apply to all businesses, including the rule that taxes on corporate profits are generally paid in the country of origin. The main difference between the GAFA and other multinationals is that their growth has been more explosive and their success more disruptive to established business models.

The GAFA are in a better position than less mature companies to pass the bill on to consumers. Increasing the tax burden of digital firms could deter both the arrival and growth of new players, and prove to be a strong barrier to competition.

Introduction

During the fall 2019 election campaign, the Liberal Party promised to introduce a 3% tax on the revenues of the Web giants earned in Canada. The revenues targeted are those from targeted advertising and digital intermediation (marketplace) services, earned by companies with annual global revenues of over $1 billion, and over $40 million in Canada. This notably includes Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Apple, collectively referred to by the acronym “GAFA.”(1)

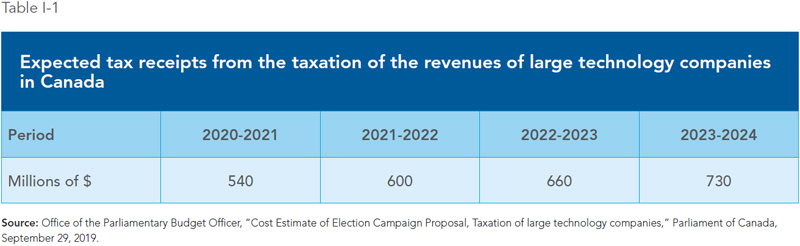

According to the Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO), such a tax would bring in $540 million for the federal government the first year it was in effect. Tax revenue could climb to $730 million by the fourth year (see Table I-1), and eventually exceed the $1-billion mark. However, the PBO itself admits that this estimate “has high uncertainty.”(2)

As in France, this tax would be in effect until the OECD member countries agree upon a form of taxation of the revenues of the tech giants, the main principle being that they would pay taxes on their profits in the countries where they generate their revenues.(3)

In Quebec, Premier François Legault has expressed his reluctance regarding the implementation of a form of taxation on the Canadian activities of these companies before the OECD unveils its final proposal, saying he would prefer to see a new regime adopted by all the OECD countries at the same time.(4) In mid-December, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said he too wants to wait until the OECD has completed its work, with this organization aiming to reach a global agreement by June 2020.(5)

Despite the recent restraint displayed by Ottawa, the approach planned by the federal government, similar to the one that has just been adopted in France, deserves to be analyzed in detail. Indeed, the French experience shows that while taxing foreign companies can be politically tempting, this kind of tax causes more problems than it resolves, and even risks being counterproductive for the Canadian economy.

References

- Philippe-Vincent Foisy, “Les libéraux veulent imposer les géants du web, dont Netflix,” Radio-Canada, September 29, 2019; Liberal Party of Canada, Forward – A Real Plan for the Middle Class, September 29, 2019, p. 79.

- Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer, “Cost Estimate of Election Campaign Proposal, Taxation of large technology companies,” Parliament of Canada, September 29, 2019.

- Joël-Denis Bellavance, “Trudeau entend taxer les géants du web… et augmenter la dette,” La Presse+, September 30, 2019; L’Express, “Taxe Gafa : l’accord France-États-Unis a-t-il sauvé le vin français?” August 27, 2019.

- Tommy Chouinard, “Taxer Google : François Legault appelle à la prudence,“ La Presse, 10 décembre 2019.

- Rania Massoud, “Taxation des géants du web : Trudeau repousse l’échéance,” Radio-Canada, December 13, 2019; Agence France-Presse, “Taxation des géants du numérique : l’OCDE vise un accord mondial d’ici juin,” Radio-Canada, October 18, 2019.