Impeding Natural Resource Development Undermines Economic Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples

Economic Note on the federal government’s obstruction of projects that would contribute significantly to the economic progress of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples

Economic reconciliation with Canada’s First Nations goes hand in hand with natural resource development, but such development is too often blocked by the federal government, according to this study published by the MEI.

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| MEI says Ottawa’s anti-energy policies killing the Canadian economy and indigenous prosperity (Western Standard, August 20, 2023)

Natural resource development is economic reconciliation (Calgary Herald, August 26, 2023) |

Interview (in French) with Gabriel Giguère (Alexandre Dubé, QUB Radio, August 17, 2023) |

This Economic Note was prepared by Krystle Wittevrongel, Senior Policy Analyst and Alberta Project Lead at the MEI, in collaboration with Gabriel Giguère, Public Policy Analyst at the MEI. The MEI’s Energy Series aims to examine the economic impact of the development of various energy sources and to challenge the myths and unrealistic proposals related to this important field of activity.

Reconciliation with Indigenous peoples has been a prominent theme in the Canadian federal government’s policy agenda for years, as has a renewed relationship between the government and First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples. The specific concept of economic reconciliation, however, has only recently established a leading position in Canadian political discourse.

The federal government’s Budget 2023 allocated $5 million “to support the co-development of an Economic Reconciliation Framework with Indigenous partners that will increase economic opportunities for Indigenous Peoples, communities, and businesses.”(1) This Framework builds on various commitments from 2022 to invest in partnerships with Indigenous communities for the development of natural resource projects.

While the concept is gaining in prominence, the federal government has yet to define what “economic reconciliation” is. According to Dale Swampy of the National Coalition of Chiefs, reconciliation—economic or otherwise—boils down to a proper strategy for solving on-reserve poverty. To many First Nations, economic reconciliation means a way to reaffirm their autonomy and self-reliance.

However, this has been undermined by the federal government’s obstruction of the growth of the natural resource industry, and especially the oil and gas sector.(2)

Economic Reconciliation Requires Natural Resource Development

For many Canadians, natural resource development projects and related work offer substantial economic and social benefits. For Indigenous Canadians who live on a reserve, these are often among the few, if not the only, economic opportunities available. According to the most recent Census, in 2021, approximately 40% of Canada’s Indigenous people lived on a reserve.(3)

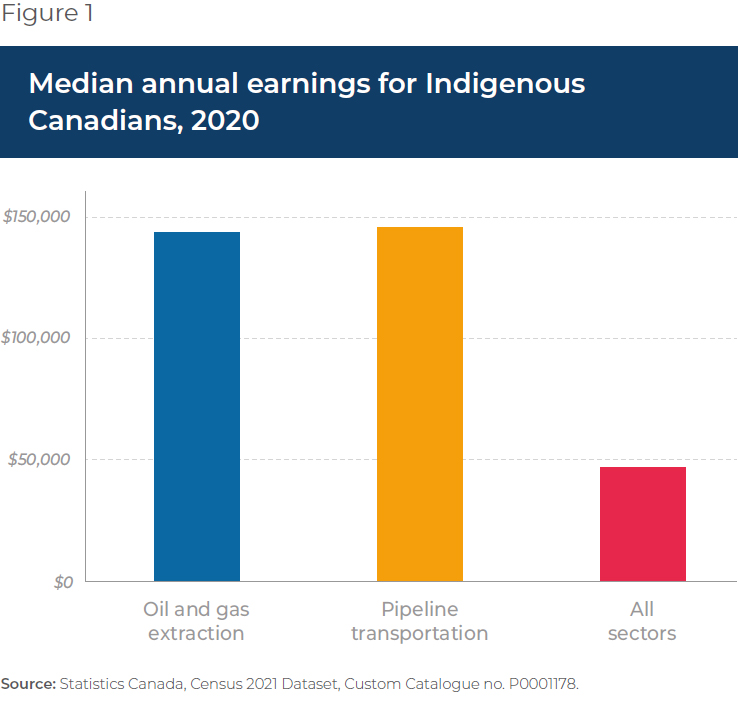

The Census also shows that for Indigenous people in Canada, oil and gas extraction and pipeline transportation were the highest paying sectors, with a median employment income of $144,000 and $146,000, respectively—over three times higher than the median income of $46,800 across all sectors(4) (see Figure 1). In addition, income growth in these sectors for Indigenous workers outpaced overall growth in all industries. In the oil and gas sector specifically, between 2019 and 2021, average earnings increased by 16.6%, compared with 8.5% for all industries.(5)

Critics of natural resource development projects often assert that Indigenous peoples are mostly opposed to them. But what they are against are projects in which they are not included or for which they bear the risk without the reward, not the principle of resource development itself. In fact, public opinion polls indicate that most Indigenous people in Canada favour natural resource development. A 2021 Environics Research poll of self-identified Indigenous people living in rural areas or on reserves found that nearly two-thirds (65%) were in support of natural resource development, while less than a quarter (23%) were opposed.(6) Indeed, in recent years, many First Nations have not only been vocal supporters of resource development, but have sought to become large-scale investors in projects.(7)

Economic reconciliation has been undermined by the federal government’s obstruction of the growth of the natural resource industry.

The obstruction of major energy projects that First Nations are supportive of, or have invested in, has actively impeded the realization of not only the associated economic benefits and opportunities, but also further community development tied to additional project benefits. Accordingly, the federal government’s stance toward these projects is at odds with its pledges to advance economic reconciliation with Indigenous peoples.

Impeded Natural Resource Development Projects: Impact Case Studies

The Northern Gateway Pipeline, Frontier Oil Sands Project, and Energy East Project are three prime examples of natural resource development projects with varying levels of Indigenous support that would have resulted in significant economic benefits for Indigenous people, and for Canadians in general, for decades to come.

Northern Gateway

The Northern Gateway Pipeline was proposed to transport synthetic crude oil and diluted bitumen from Alberta’s oil sands to a marine terminal in British Columbia, ultimately providing access to new Asian markets for Canadian oil sands production. It was estimated that at full capacity, 525,000 barrels per day could have been transported, starting in late 2018 and operating to 2048.(8) This amount could have supplied the daily electrical needs of 29.3 million dwellings, nearly twice as many as Canada had in 2021.(9) If all shipped abroad, this would have increased Canada’s crude oil exports by 14% in 2019.(10)

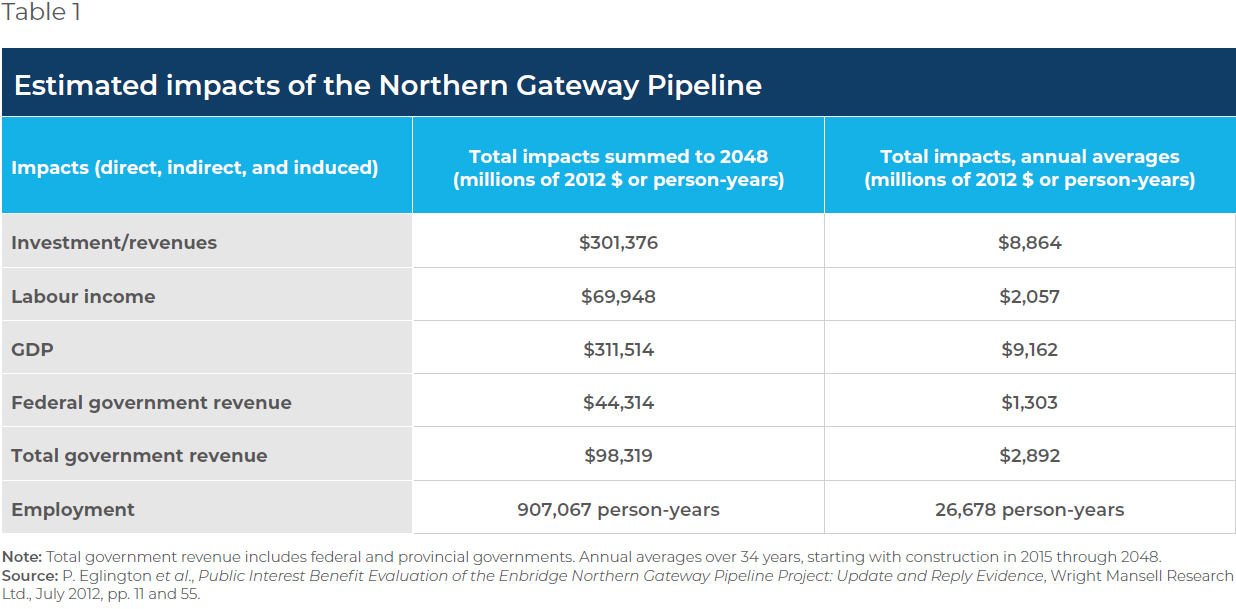

Cost-benefit analyses of the project were positive, with high estimated net economic benefits in all scenarios, even when unfavourable-to-project sensitivity cases were considered that included higher social discount rates, lower oil prices, and greater possible negative environmental impacts. One conservative estimate arrived at a $312-billion GDP gain, 907,000 person-years of employment, and a $98-billion increase in government revenue(11) (see Table 1).

For context, a $312-billion GDP gain is around $9.2 billion per year on average annually, which is just under the combined total that Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba will receive in 2023-2024 through Canada Health Transfer funding from the federal government.(12) A $98-billion total increase in government revenue over the operating period is $2.9 billion annually, which is about the total amount the federal government has spent on infrastructure projects to expand access to clean drinking water on reserves.(13) In terms of employment, annually, the project would have supported 26,678 full-time jobs, which is just under the total workforce of Air Canada, one of Canada’s largest employers.(14)

The project was supported by 26 Indigenous equity partners (nearly 60% of the identified Indigenous communities along the pipeline’s right-of-way) which had agreed to a 10% equity stake expected to generate around $280 million in net income over the first 30 years.(15) There were also reported promises of $2 billion set aside for business and employment opportunities for Indigenous communities.(16)

A 2021 poll of Indigenous people living in rural areas or on reserves found that 65% support natural resource development.

Despite these favourable forecasts and Indigenous support, the project was rejected by the federal government in 2016.(17) Leaders of a number of affected First Nations were disappointed in the decision which, according to them, was made without their input and was merely political in nature.(18)

Frontier

The Frontier Oil Sands Project was to include the construction, operation, and reclamation of an oil sands surface mine in northeast Alberta, which at full capacity would have produced 260,000 barrels per day of bitumen for 41 years, starting in 2026.(19) The project was to be one of the largest in the history of Canadian oil development and was expected to yield substantial benefits, including $19.1 billion in GDP during construction alone, and $2.2 billion annually while in operation.(20) The project would have employed significant numbers of Canadians, notably local Indigenous labour that may not have alternative employment in the absence of the mine.(21)

The project team engaged extensively with Indigenous peoples and reached agreements with all 14 Indigenous communities in the project region after more than a decade of negotiations with them.(22) Overall, the Indigenous communities in the project region were supportive of the project, although the precise economic benefits directed to these communities remain undisclosed.(23)

Despite all this, the week that Cabinet was set to decide whether to approve, delay, or reject the project, Teck Resources withdrew its regulatory application from the federal environmental assessment process and abandoned the project due to ongoing climate politics and lack of a framework that reconciles resource development and climate change, despite “unprecedented support from Indigenous communities.”(24) So, while the federal government technically didn’t cancel this project, its ambiguous policies were a formidable hurdle to development and played a lead role in making the project unprofitable.

Energy East

The Energy East Project was to construct over 1,500 km of new pipeline and also convert and utilize about 3,000 km of existing natural gas pipeline.(25) Once completed, it would have transported 1.1 million barrels of crude oil per day from Alberta and Saskatchewan to coastal refineries and marine terminals in Eastern Canada during its estimated 40 years of operation. It would have displaced foreign oil and created another channel for producers to ship overseas and diversify markets.(26)

The project proponent, TransCanada, had consulted with 166 First Nations and Métis communities along the pipeline and had developed a number of economic, educational and training, and partnership opportunities linked to the project, as well as ample community investment initiatives.(27) Cost-benefit analysis modelling showed significant economic benefits, as well as the addition of 321,000 one-year full-time equivalent jobs in the construction and operation phases of the project.(28) However, in 2017, the company cancelled the project after new emission criteria were put in place by the National Energy Board, on top of already costly regulatory delays.(29) Again, while the government didn’t actively cancel this project, it clearly obstructed it to the point where it was no longer deemed profitable.

Conclusion

Economic reconciliation with Indigenous peoples will not get far with the government actively impeding natural resource development projects that would contribute significantly to their economic progress. In fact, according to Karen Ogen-Toews, former chief of the Wet’suwet’en First Nation and the CEO of the First Nations LNG Alliance, the oil and gas sector is critical to economic reconciliation, and through consultation, community investments, and real partnership opportunities, can “ensure our people are taken care of, and all the wrongs are made right.”(30) According to Dale Swampy, “Proper economic reconciliation was hurt by the federal government moving to stop industries like the oil and gas industry. We think that’s a step backwards for us.”

The federal government must give more weight to the economic and community development outcomes of natural resource projects.

Fort McKay First Nation in Alberta provides an example of how partnership building with industry and natural resource development can advance economic reconciliation. It has lower unemployment than other First Nations in Canada, and also has the highest median household income of any First Nation in North America.(31) But this didn’t happen overnight; it took decades of partnerships—both official and unofficial—with the companies in the area. The federal government, in order to fulfill its stated commitment to reconciliation, must give more weight to the economic and community development outcomes of natural resource projects, for the benefit of Indigenous peoples across the country.

References

- Government of Canada, Budget 2023: A Made in Canada Plan, 2023, pp. 127 and 129.

- Personal communication between the author and Dale Swampy of the National Coalition of Chiefs, May 19, 2023. The author thanks Mr. Swampy for his time.

- Idem.; Dale Swampy, “Indigenous Canadians want natural resources development – why aren’t we being heard?” Financial Post, November 1st, 2019; Statistics Canada, Table: 98-10-0267-01: Membership in a First Nation or Indian band by residence on or off reserve: Canada, provinces and territories, 2023.

- Catalogue no. P0001178 custom dataset Census 2021 dataset from Statistics Canada, calendar year 2020. NAICS code 211 = oil and gas extraction; 486 = pipeline transportation. “Indigenous” includes all self- identified First Nations, Métis, and Inuit people. The author thanks Heather Exner-Pirot for sharing this custom dataset.

- Catalogue no. 71C0003, custom Labour Force Survey dataset from Statistics Canada for the years 2019-2021. The author thanks Heather Exner-Pirot for sharing this custom dataset.

- Heather Exner-Pirot and John Desjarlais, “Majority of Indigenous peoples support natural resource development,” Commentary, MacDonald-Laurier Institute, September 2022, pp. 1-4.

- Ibid., pp. 3-7; J.P. Gladu and Ken Coates, “Buying back Canada: Indigenous investors are no longer small-time players,” Toronto Star, April 15, 2023.

- P. Eglington et al., Public Interest Benefit Evaluation of the Enbridge Northern Gateway Pipeline Project: Update and Reply Evidence, Wright Mansell Research Ltd., July 2012, pp. 6 and 11.

- Author’s calculations. The average Canadian home uses 11,135 kWh of electricity per year and, assuming that oil is used to generate electricity, one barrel of oil equivalent contains 1,700 kWh. According to the 2021 census there were 16,284,235 private dwellings in Canada. Energyrates.ca, Residential Electricity and Natural Gas Plans, consulted July 5, 2023; US Department of Energy, “Chapter 3: Biomass to biofuels: glossary of terms and conversion factors,” Bioenergy (Second Edition): Biomass to Biofuels and Waste to Energy, Academic Press, 2020, p. 52; Statistics Canada, Type of Dwelling Reference Guide, Census of Population, 2021, April 27, 2022.

- Canada Energy Regulator, “Market snapshot: Canadian crude oil is mainly exported to two regions in the United States,” June 30, 2022.

- P. Eglington et al., op. cit., endnote 8, pp. 11 and 95.

- Government of Canada, Federal transfers to provinces and territories, Federal transfers to Provinces and Territories – 2014-15 to 2023-24, Canada, Major federal transfers, December 2022, consulted July 6, 2023.

- Government of Canada, Investing in Indigenous community infrastructure, Waste and wastewater, March 24, 2023.

- Mediacorp Canada Inc., Air Canada, February 27, 2023.

- Kennedy A. Bear Robe and Robin A. Dean, “Case Commentary: Gitxaala Nation V. Canada, 2016 FC! 187,” Miller Thompson Lawyers, July 14, 2016; CBC News, “Majority of aboriginal communities sign on to Northern Gateway,” June 5, 2012.

- Claudia Cattaneo, “‘We are very disappointed’: Loss of Northern Gateway devastating for many First Nations, chiefs say,” Financial Post, April 10, 2017.

- The project was rejected after a judicial decision determined that a number of First Nations were not adequately consulted. Federal Court of Appeal Decision, Gitxaala Nation v. Canada, June 23, 2016; Andrew Reeves and Nathan Baker, “Northern Gateway Pipeline Proposal,” Canadian Encyclopedia, January 30, 2020.

- Claudia Cattaneo, op. cit., endnote 16.

- Teck Resources Ltd., “The Frontier Project: Building a leader in responsible energy production,” assessed June 21, 2023, p. 2; Chris Joseph, Thomas I. Gunton, and James Hoffele, “Assessing the public interest in environmental assessment: lessons from cost-benefit analysis of an energy megaproject,” Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, Vol. 38, No. 5, 2020, pp. 397 and 409.

- In addition to $72.2 billion in government revenue. All dollars in 2017 CDN. Chris Joseph, Thomas I. Gunton, and James Hoffele, idem.

- Estimated 278,000 person-years of total employment, including 7,000 construction jobs and 2,500 operating jobs. Ibid., pp. 397 and 399; Teck Resources Ltd., op. cit., endnote 19, p. 5.

- Teck Resources Ltd., Ibid., p. 8; David Thurnton, “Fort McMurray region’s Indigenous groups support oilsands mine, company tells review panel,” CBC News, September 25, 2018; Rod Nickel, “Teck oil sands project splits Canada’s Indigenous peoples, poses challenge for Trudeau,” Reuters, January 21, 2020.

- Jeff Labine, “Indigenous communities in northeastern Alberta show support for Teck Frontier oilsands mine,” Edmonton Journal, January 6, 2020; Rod Nickel, idem.

- Teck Resources Ltd, “Teck Withdraws Regulatory Application for Frontier Project,” News Release, February 23, 2020.

- National Energy Board, TransCanada Pipelines Limited and Energy East Pipeline Ltd., Energy East Project and Asset Transfer Applications, May 2016, p. 5.

- Government of Canada, Energy East Project, October 10, 2017; Canada Energy Regulator, Energy East and Energy Mainline Projects, September 29, 2020; CBC News, “Energy East pipeline may create 10,000 jobs, study says,” September 10, 2013.

- Elizabeth Harrison, “An Analysis of the Adequacy of Crown Consultation with Indigenous Peoples on the Energy East Pipeline and an Overview of the Relevant Law of the Duty to Consult,” Nature Canada, August 2017, p. 12; Canada Energy Regulator, A76905 Energy East Pipeline Ltd. – Consolidated Project and Asset Transfer Applications-Volume 1-Application and Project Overview; Energy East Pipeline Ltd., Consolidated Application, Volume 10: Aboriginal Engagement, May 2016, pp. 1-14.

- Peaking at almost 48,700 during the construction phase and then levelling out at around 7,900 jobs during the operations phase. Estimated to add $33.9 billion to Canadian GDP and $7.6 billion in total tax revenue to Canada during the first 28 years of construction and operation. Zoey Walden and Julie Dalzell, An Economic Analysis of TransCanada’s Energy East Pipeline Project, Canada Energy Research Institute, Study No. 140, May 2014, pp. 16-23.

- Ethan Lou, “Canada to consider indirect emissions for TransCanada Energy East pipe,” Reuters, August 23, 2017; Deborah C. Sawyer and Nathan Baker, “TC Energy (formerly TransCanada),” Canadian Encyclopedia, June 10, 2021.

- Statement made June 12, 2023 at the National Coalition of Chiefs Natural Resources Summit in Calgary.

- Statistics Canada, Aboriginal Population Profile, 2016 Census, June 19, 2019; Statistics Canada, Indigenous Peoples Thematic Series, A snapshot: Status First Nations people in Canada, Chart 4, Employment rate among individuals aged 25-64, Canada, 2006 and 2016, April 10, 2021; Personal communication with Dale Swampy, May 19, 2023 as well as statement made publicly June 12, 2023 at the National Coalition of Chiefs Natural Resources Summit in Calgary; see also Tom Flanagan, The Community Capitalism of the Fort McKay First Nation: A Case Study, Fraser Institute, 2018.