Emergency Rooms: When Patients Leave Untreated

Viewpoint showing that more than one in ten Quebec patients who goes to an ER leaves without being treated

Last year, nearly 380,000 Quebecers—or over 1,000 patients a day—ended up leaving a hospital emergency room without having been attended to by a doctor, shows this publication.

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| 1,000 patients a day left Quebec emergency rooms last year without being treated: study (CTV News, January 29, 2020)

1000 patients quittent l’urgence quotidiennement sans se faire soigner (TVA Nouvelles, January 29, 2020) Des milliers de Québécois quittent les urgences sans avoir vu un médecin (La Presse, January 29, 2020) Mille personnes par jour repartiraient de l’urgence sans avoir été vues au Québec (Ici Radio-Canada, January 29, 2020) Quebec’s overflowing emergency rooms are a symptom of a deeper problem (National Post, January 31, 2020) |

Interview (in French) with Patrick Déry (Facteur matinal, Ici Radio-Canada, January 29, 2020)

Interview (in French) with Patrick Déry (Que l’Outaouais se lève, 104.7 FM, January 30, 2020) |

Interview (in French) with Patrick Déry (Mario Dumont, LCN-TV, January 29, 2020)

Commentary (in French) by Mario Dumont (Mario Dumont, LCN-TV, January 29, 2020) Interview with Patrick Déry (CTV News at 5, CFCF-TV, January 31, 2020) |

This Viewpoint was prepared by Patrick Déry, Senior Associate Analyst at the MEI. The MEI’s Health Policy Series aims to examine the extent to which freedom of choice and entrepreneurship lead to improvements in the quality and efficiency of health care services for all patients.

Once again, the holiday period was a difficult one in Quebec hospitals. Shortly after New Year’s, the occupation rate of many emergency rooms exceeded 150%. Some reached 200%, and one Montreal hospital even registered a rate of 250%.(1) This means that there were five patients for every two available stretchers. The seasonal flu undoubtedly added to the difficulties in the system, but it’s hard to blame a predictable annual phenomenon for problems that have endured for decades.(2)

Overflowing ERs are a symptom of a deeper problem. Despite the addition of ever more public funds, central planning by the department and a multitude of barriers prevent a better allocation of resources and their optimal use. Thus, one in five Quebecers still doesn’t have a family doctor, and in Montreal it’s nearly one in three.(3) Those who are looking for one can wait years, even for priority cases,(4) and their number just keeps rising.(5)

Emergency rooms therefore become the health care system entry point for many patients. Over half (55%) of Quebecers visiting emergency rooms are assigned a priority level of 4 or 5, which generally corresponds to a condition that can be treated in a clinic.(6)

Despite all the political and media attention our health care system has received, and despite the considerable—and growing—sums of money injected into the health care system each year, wait times are stagnating or getting worse: The median length of stay for patients on stretchers is the same as it was fifteen years ago, while it has increased 50% for ambulatory patients.(7)

Patients Who Leave

Each year, Quebec emergency rooms receive some 3.7 million visitors. Of this number, around 3.2 million are attended to and treated on site. A portion of these patients are redirected within the health care system. The rest leave without having been seen by a doctor.(8)

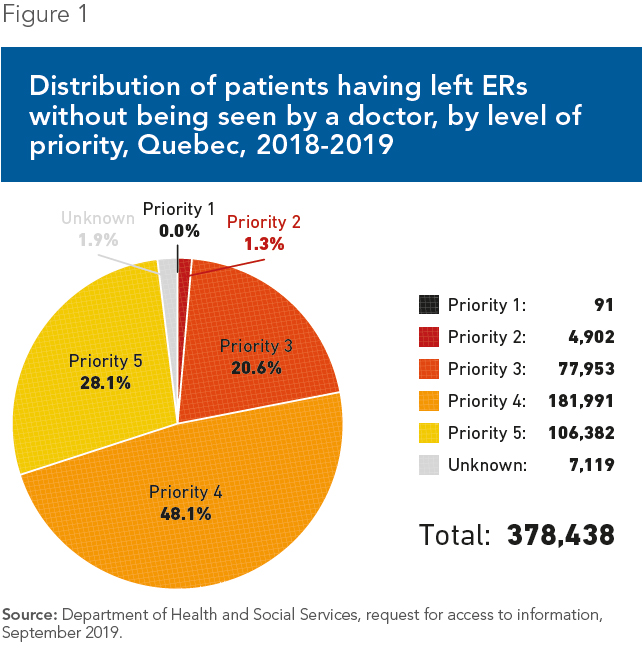

Last year, nearly 380,000 Quebecers—or over 1,000 patients a day—went to a hospital emergency room and ended up leaving without having been attended to by a doctor, and without having been redirected, according to the data from Quebec’s Department of Health (see Figure 1). That means more than one in ten patients gave up on receiving care. Yet over one fifth of these patients had been classified as “very urgent” or “urgent” during triage (Priority 2 or 3), which indicates that their condition “is potentially life-threatening” or “could put [the patient’s] life in danger.”(9)

For the second year in a row, the Department of Health has tried to reduce emergency room overcrowding with winter clinics. However, the 29,000 patients treated by these clinics between January and March 2019(10) represented just a drop in the bucket among the millions of consultations demanded by Quebecers last year, in ERs and otherwise. The Minister herself recognized that the contribution of the winter clinics “is insufficient” and “much more is needed.”(11) In sum, our health care system is unable to meet the demand, while the effects of the aging of the population are just starting to be felt.(12)

Doing More with Less

Despite health care spending that is on par with that of the top OECD group, Quebec and Canada as a whole are below the average for these same countries in terms of resources available for patients.(13) No public policy will be able to change this state of affairs overnight. If the government wants to see an improvement, it has no choice but to use its limited resources in the most efficient possible way and do everything it can to lower the barriers that prevent patients from accessing care, even at the cost of upsetting certain interest groups.

Expanding the scope of practice of health professionals, notably that of nurse practitioners and pharmacists, could make a difference in the short term. Despite some recent progress, their autonomy is still needlessly restricted when compared to what is done elsewhere in Canada and in other similar countries.(14) The skills of other, non-practitioner nurses could also be put to better use, as has been done for several years now in Northern Quebec.(15)

Other measures will only have a longer term impact, but can nonetheless be started now. Along with the reform of fee-for-service payments for doctors (a method of remuneration that discourages delegation and innovation in their practices),(16) the government should put an end to medical school admissions quotas. A surplus of doctors would be a happy problem, and one that Quebec is far from having.(17)

Finally, the government must take advantage of the upcoming introduction of activity-based funding in hospitals(18) to entrust the administration of some of these to entrepreneurs, all while maintaining the universal character of our health care system, as is done in most industrialized countries.(19) This combination has led to better results with equal resources, or to equally good results using fewer public resources, as illustrated by the performance of entrepreneurial hospitals in Europe, and by the superior quality of private funded CHSLDs here in Quebec.(20)

References

- La Presse, “Les urgences débordent à travers le Québec,” January 4, 2020.

- See for example Nicole Beauchamp, “Hôpitaux : Québec met de l’ordre dans les urgences,” La Presse, March 11, 1980; Martha Gagnon, “Les omnipraticiens lancent un nouvel appel pour décongestionner les urgences,” La Presse, December 7, 1988, p. A3.

- Department of Health and Social Services, Accès aux services médicaux de première ligne, Données sur l’accès aux services de première ligne, September 30, 2019 (preliminary data), Table 1. Author’s calculations.

- Davide Gentile, “Guichet d’accès à un médecin de famille : plus de patients, plus d’attente,” Radio-Canada, May 10, 2019; Radio-Canada, “Accès à un médecin : des délais qui s’allongent à mesure que le temps passe,” July 31, 2018; La Presse, “Dans l’attente d’un médecin de famille,” July 23, 2019.

- Between January and July 2019, the number of Quebecers waiting for a family doctor grew from 500,497 to 577,509, a 15% increase in just six months. Régie de l’assurance maladie, “Évolution du nombre de personnes inscrites au Guichet d’accès à un médecin de famille (GAMF) selon leur statut en 2019,” Government of Quebec.

- Department of Health and Social Services, op. cit., endnote 3, Table 4. Author’s calculations.

- Patrick Déry, “Emergency Rooms: Fewer Patients, Longer Waits,” Viewpoint, MEI, August 21, 2019.

- Department of Health and Social Services, request for access to information, September 2019.

- CHU de Québec, Triage aux urgences, Niveaux de priorité selon de l’Échelle canadienne de triage et de gravité, page updated July 11, 2019.

- Department of Health and Social Services, “Première année des cliniques d’hiver – La ministre McCann souligne les retombées positives de cette nouvelle initiative,” Press release, April 23, 2019.

- Tommy Chouinard, “Urgences: ‘On a besoin de faire beaucoup plus’, dit McCann,” La Presse, January 14, 2020.

- Institut de la statistique du Québec, Perspectives démographiques du Québec et des régions, 2011-2061, Édition 2014, September 9, 2014, p. 111.

- Notably for the number of hospital beds, the number of nurses, and the number of doctors, the latter being especially low here. Canadian Institute for Health Information, OECD Interactive Tool: International Comparisons — Peer countries, Quebec, page consulted on January 14, 2020; OECD, Health at a Glance 2019, OECD Indicators, 151, 153, 173, 179, and 195; Institut de la statistique du Québec, Québec Handy Numbers, 2019 Edition, May 10, 2019, p. 20.

- Patrick Déry, “Should Super Nurses Be Allowed to Make Diagnoses?” Viewpoint, MEI, February 28, 2019; Canadian Pharmacists Association, Pharmacy in Canada, Pharmacists’ Expanded Scope of Practice.

- Jean Tremblay, “Des infirmières avec plus de responsabilités dans le Nord,” Le Journal de Montréal, May 18, 2015.

- Patrick Déry, Health Care Entrepreneurship – How to Encourage the Deployment of Telemedicine in Canada, Research Paper, MEI, September 19, 2019, pp. 32 and 44.

- Patrick Déry, “It’s Time to End Med School Quotas,” Viewpoint, MEI, March 15, 2018.

- Patricia Cloutier, “Pour que l’argent suive le patient,” Le Soleil, July 23, 2019.

- Yanick Labrie, For a Universal and Efficient Health Care System: Six Reform Proposals, Research Paper, MEI, March 13, 2015, p. 20.

- Patrick Déry, “Does Entrepreneurship Make a Difference in Health Care? The Case of Private Funded CHSLDs,” Viewpoint, MEI, October 3, 2019.