Viewpoint – Food-Truck Freedom for Montreal

Since 2013, there has been a loosening of the decades-long ban on mobile food vending in Montreal. Such steps place Montreal squarely within a wider movement throughout North America to allow greater entrepreneurship at the municipal level. In spite of this positive step, however, the large potential benefits to both consumers and workers are being undermined by heavy regulation. This Viewpoint highlights those benefits and explains how the regulatory framework surrounding mobile food vendors in Montreal remains much too constraining.

Media release: Food trucks in Montreal face too many regulatory roadblocks

Links of interest

Links of interest

|

|

|

|

Le rêve brisé d'exploiter un camion-restaurant (Le Huffington Post Québec, May 16, 2016)

Montreal should let food trucks satisfy consumer appetites (Montreal Gazette, May 18, 2016) |

Interview (in French) with Vincent Geloso (Martineau, CHOI FM, May 13, 2016) |

Interview (in French) with Vincent Geloso (Mario Dumont, LCN, May 13, 2016)

Interview with Vincent Geloso (CTV News Montreal, CFCF-TV, May 18, 2016) |

Viewpoint – Food-Truck Freedom for Montreal

Since 2013, there has been a loosening of the decades-long ban on mobile food vending in Montreal. Such steps place Montreal squarely within a wider movement throughout North America to allow greater entrepreneurship at the municipal level. In spite of this positive step, however, the large potential benefits to both consumers and workers are being undermined by heavy regulation. This Viewpoint highlights those benefits and explains how the regulatory framework surrounding mobile food vendors in Montreal remains much too constraining.

The Economics of Mobile Food Vending

In North American cities where this industry is liberalized, mobile food vending is a low-cost entrepreneurial opportunity with limited personal risk. Since the start-up costs are much lower than those associated with a brick-and-mortar restaurant, it is ideally suited for those with less capital to invest. Exit costs are also very small, so in the eventuality of failure, vendors can more easily exit the industry. As a result of these factors, mobile food vending is a very appealing opportunity for low-income households seeking to raise their living standards.(1)

The owners of fixed venues also benefit from the presence of food trucks. Although restaurateurs may have to work a little harder, there are important incentive effects that flow from competition.(2) Moreover, there are cases in which, thanks to the ability of mobile vendors to attract consumers to a particular area, revenues for fixed venue owners actually increase.(3)

For consumers, the gains are substantial. For one thing, not all areas are well-served by restaurants. Mobile food vendors thrive in such conditions, offering food services where none had existed before.(4) There are also side benefits from mobile food vendors making streets safer.(5) With regard to quality, complaints against mobile food vendors tend to be made by competitors, and in 80% of cases are unsubstantiated.(6) A study surveying statistics from a sample of seven major American cities found that mobile food vendors are just as safe and sanitary as restaurants, and often more so.(7)

Costs of Burdensome Regulation

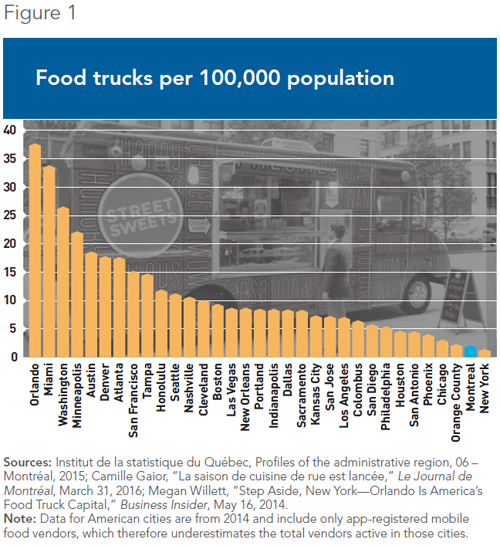

The food truck industry that the City of Montreal has recently allowed to emerge, after decades of simply banning street vending, is unfortunately heavily regulated. A prospective vendor must acquire a permit of operation, only 41 of which were issued this year(8) (see Figure 1). In order to do so, a request must be submitted along with a business plan to a committee of five individuals—three of whom are associated with the restaurant industry—which will assess the viability of the project. The number of permits that can be issued is limited to 1.5 times the number of food truck spots designated by the city. Each site can only have a maximum of three vendors on it at a time, and vendors are prohibited from selling except at designated sites.(9) Permits will not be issued to prospective vendors who do not already own a restaurant.(10) Finally, the price of an annual permit stands at $2,075—or $1,215 for a seasonal permit(11)—on top of all of the other costs associated with regulatory compliance.

Montreal’s heavy burden of regulation is actually quite similar to those found in the city of Chicago. In essence, both cities have adopted regulations to restrict mobile food vendors in order to avoid disturbing restaurant owners.(12) The burden of municipal ordinances restricting mobile vending in Chicago falls disproportionately on poorer individuals, a lot of whom are immigrants.(13) Many of these individuals work anyway, but do so illegally. The removal of burdensome regulations would see 2,145 jobs legalized and an additional 6,435 jobs created. There would be an increase of from $40 million to $160 million in total annual sales, and a corresponding increase of from $2.1 million to $8.5 million in new local sales tax revenues.(14)

It is clear that there would be tremendous benefits to the loosening of regulations in Montreal as well. Opting for a single and reasonable flat-fee permit, basic health standards, and regular inspections instead of the tight restrictions that exist now would allow these benefits to materialize all while continuing to protect consumers.(15)

To avoid resistance to such beneficial reform, the city should consider including, as part of a broader plan, measures to alleviate the burdensome regulations and taxes it imposes on restaurants, too. According to one study of business regulations, based on opening a restaurant in different cities in Quebec, Montreal ranked 74th out of 100 in terms of ease of doing business. A large part of that poor performance is explained by a heavy regulatory and fiscal burden.(16) By loosening the regulatory framework for everyone, the benefits mentioned above would be greatly amplified, since the competitiveness of the food vending sector as a whole would improve.

This Viewpoint was prepared by Vincent Geloso, Associate Researcher at the Montreal Economic Institute, and Jasmin Guénette, Vice President of the MEI. The MEI’s Regulation Series seeks to examine the often unintended consequences for individuals and businesses of various laws and rules, in contrast with their stated goals.

References

1. Erin Norman et al., Streets of Dreams: How Cities Can Create Economic Opportunity by Knocking Down Protectionist Barriers to Street Vending, Institute for Justice, July 2011, pp. 9-14.

2. H.G. Parsa et al., “Why Restaurants Fail,” Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, Vol. 46, No. 3, August 2005, pp. 304-322.

3. Gregg Kettles, “Regulating Vending in the Sidewalk Commons,” Temple Law Review, Vol. 77, No. 1, 2004, pp. 31-32.

4. See Erin Norman et al., op. cit., endnote 1.

5. Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Vintage Books, 1992 [1961], p. 34.

6. Deanne Petersen, Food Truck Fever: A Spatio-Political Analysis of Food Truck Activity in Kansas City, Missouri, Department of Landscape Architecture/Regional & Community Planning, College of Architecture, Planning and Design, Kansas State University, p. 24.

7. Angela C. Erickson, Street Eats, Safe Eats: How Food Trucks and Carts Stack Up to Restaurants on Sanitation, Institute for Justice, June 2014.

8. Camille Gaior, “La saison de cuisine de rue est lancée,” Le Journal de Montréal, March 31, 2016.

9. Private venues, like the Olympic Stadium, are allowed to invite food trucks onto their premises.

10. Ville de Montréal, By-law 15-039 Governing Street Food, March 2015.

11. Ville de Montréal, By-law 15-091 Concerning Fees (Fiscal 2016), article 17, April 2016.

12. Elan Shpigel, “Chicago’s Over-Burdensome Regulation of Mobile Food Vending,” Northwestern Journal of Law and Social Policy, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2015, pp. 354-388. Note the only exception is that Chicago does not limit the operation of food trucks to restaurant owners, but it does establish other restrictive rules to protect restaurant owners, notably a distance-to-restaurant rule which basically prohibits competition for most of Chicago.

13. Nina Martin, “Food Fight! Immigrant Street Vendors, Gourmet Food Trucks and the Differential Valuation of Creative Producers in Chicago,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Vol. 38, No. 5, August 2014, pp. 1867-1883.

14. Michael Lucci and Hilary Gowins, Chicago’s Food-Cart Ban Costs Revenue, Jobs, Special Report, Illinois Policy Institute, August 2015, p. 2.

15. Robert Frommer and Bert Gall, Food Truck Freedom: How to Build Better Food-Truck Laws in Your City, Institute for Justice, November 2012.

16. Thomas Tellanger and Simon Gaudreault, Le casse-tête municipal des entrepreneurs : Analyse de la réglementation imposée aux PME dans les 100 plus grandes villes du Québec, Canadian Federation of Independent Business, January 2016, p. 13.