The Dangers of a Pan-Canadian Drug Insurance Program

Economic Note examining how a countrywide public drug insurance monopoly would reduce coverage quality for a large number of Canadians and considerably increase public spending

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| 21.5 million Canadians to have insurance coverage jeopardized by pharmacare: research (True North, February 27, 2024)

Think tank warns federal pharmacare bill represents overreach that could worsen coverage (Western Standard, February 29, 2024) Federal pharmacare is a bomb waiting to detonate your coverage (National Post, March 2, 2024) National pharmacare program could put majority of Canadians at risk – MEI report (Benefits and Pensions Monitor, May 4, 2024) |

Interview with Emmanuelle B. Faubert (The Shift with Patty Handysides, AM 800, February 29, 2024)

Interview (in French) with Emmanuelle B. Faubert (Mario Dumont, QUB Radio, March 4, 2024) Interview with Emmanuelle B. Faubert (Shaye Ganam, Global Radio, March 5, 2024) |

This Economic Note was prepared by Emmanuelle B. Faubert, Economist at the MEI. The MEI’s Health Policy Series aims to examine the extent to which freedom of choice and entrepreneurship lead to improvements in the quality and efficiency of health care services for all patients.

The issue of drug insurance, or pharmacare, resurfaces regularly in political debates. In June 2023, the New Democratic Party (NDP) tabled Bill C-340, the Canada Pharmacare Act,(1) aiming to standardize the criteria that provincial drug insurance programs will have to meet in order to receive federal funds. Following the initial failure of this initiative, the NDP and the Liberal Party agreed that the government would table a new bill by March 1st, 2024.(2) However, it is not known what precise form this insurance program will take, or what the extent of its coverage will be.

The arguments generally put forward in favour of adopting a pan-Canadian drug insurance program are many, but the one that is at the centre of the debate concerns the non-negligible number of Canadians who do not have coverage. It is also argued that having a single payer would provide greater negotiating power, which would help reduce the prices of medication across Canada.

This study examines the public costs of implementing this kind of program, as well as the adverse effects of such a centralized approach.

Reducing Coverage and Choices for Canadians

As health care is a provincial jurisdiction, drug coverage varies widely from coast to coast. Each province nonetheless offers at least one form or another of drug insurance. Certain programs aim to cover the general population, while others are more targeted.(3)

Moreover, several provinces provide what is known as a “catastrophic” drug insurance plan, which covers only drugs considered expensive, in order to help citizens cover the costs of certain medication when these exceed a given percentage of their income.(4) While this coverage is minimal, it nonetheless acts as a safety net for Canadians normally ineligible for regular forms of insurance, even if this safety net is not used in the end because they were in good health.

Changing the list of insured medications following the adoption of a pan-Canadian drug insurance program would certainly have an immediate impact on Canadian patients, especially those currently covered by private insurance.

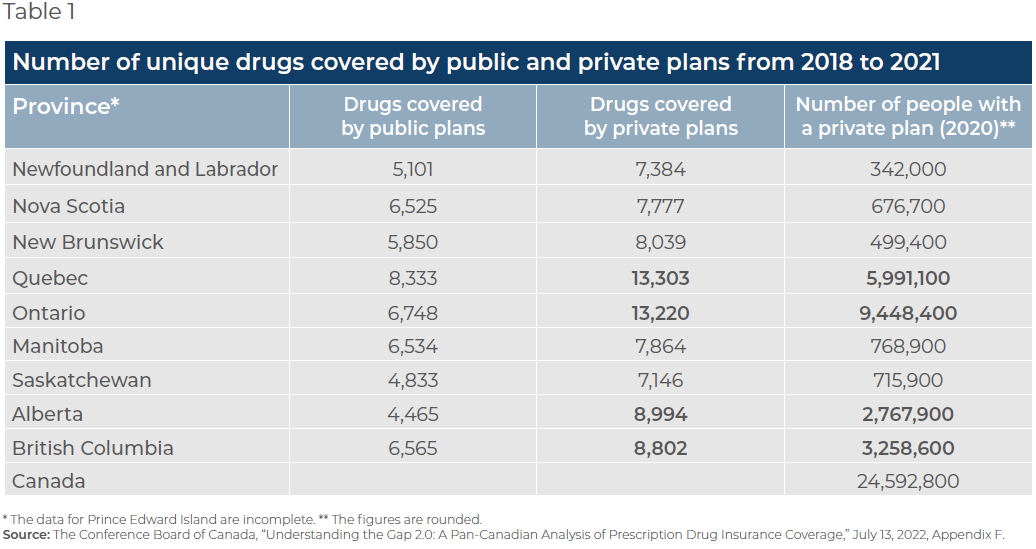

Overall, private insurance covers more drugs than the public insurance plans of provincial governments (see Table 1). Between 2018 and 2021, private plans on average reimbursed 51% more unique medications(5) than the public plans.(6)

For example, in Quebec, the province with the longest list of drugs covered by a public insurance plan, the difference was 59.6%, private insurers in Quebec also being among the most generous in Canada.

Even if the list adopted under the new federal pharmacare act were identical to that of the Régie de l’assurance maladie du Québec (RAMQ), it would reduce the number of insured drugs for a large number of Canadians. The four most populous provinces in the country (Ontario, Quebec, British Columbia, and Alberta) have private coverage that is more extensive than that of the RAMQ. In 2020, 24.6 million Canadians had private drug insurance, representing 64.9% of the Canadian population.(7) Of this number, 21.5 million were living in these four provinces. This means that up to 21.5 million Canadians would experience a reduction in the quality of their drug coverage with the adoption of pharmacare.(8)

According to the criteria put forward by the NDP, the new law would probably prohibit purchasing complementary insurance that provides additional coverage for drugs that are not covered, or only partially so. Patients would then have two choices: pay out-of-pocket for their usual drugs, or go without.

However, as some pharmacists are already pointing out, if certain drugs are no longer covered by an insurance plan, it is very likely that pharmaceutical companies will stop distributing them in Canada. The variety of medications in circulation in this country is therefore at risk of shrinking, preventing previously covered patients from having access to these drugs, even if they were disposed to pay for them out of their own pocket.(9)

It must be noted that at root, medicine has to take into account the distinctive features of individuals, as the effectiveness of a given treatment varies greatly from one patient to another. Preserving access to a wide variety of treatments is therefore crucial, yet a new pharmacare program may well pose a threat to such access.

21.5 million Canadians would experience a reduction in the quality of their drug coverage with the adoption of pharmacare.

To this is added the risk—should this program succeed in lowering drug prices substantially—of undermining pharmaceutical innovation and Canadians’ future access to those innovations.

The process that allows a drug to be offered to Canadians in a health facility is very complex and takes several years.(10) A drug must first be approved by Health Canada, following a rigorous battery of tests.(11) The Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) then determines its maximum price, after which the price is negotiated through the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance. It must then be approved by the provincial health authorities to be added to the list of drugs covered by a province’s public plan.(12)

If pharmaceutical companies find themselves in a power struggle that drags prices down considerably, they will prefer to launch and supply their new drugs in markets where they will be able to earn a return on their research investments. Canadians will thus have to wait longer before a new drug is submitted by a pharmaceutical company and approved by Health Canada, and even longer before it is covered by the new universal pan-Canadian insurance plan.

Furthermore, the pharmaceutical sector is not immune to the slowness of the governmental apparatus.(13) Consequently, Canadians with private insurance obtain access to new drugs an average of 226 days, or a little over seven months, after approval by Health Canada, versus 732 days,(14) or two years, for those on a public plan. Canadians covered by public insurance must therefore wait on average a year and five months more than those with a private insurance policy before being able to be reimbursed for a new drug on the market.

While 44% of new drugs launched on the global market between 2012 and 2021 are distributed in Canada, only 20% are covered by the public plans.(15)

In a context in which the upstream approval process already takes over a year,(16) we run the risk of delaying even further the treatment of patients who depend on the results of pharmaceutical research.

Explosion of Public Costs

Even if we focus on costs, the financial advantage of a universal drug insurance program is not clear, notably from a public finances perspective.

First, moving all Canadians to a public drug insurance system will exert an enormous amount of upward pressure on public drug spending, especially as private insurance spending gets transferred to the public accounts. As mentioned above, a substantial proportion of the Canadian population is currently privately insured.

Canadians with private insurance obtain access to new drugs an average of seven months after approval by Health Canada, versus two years for those on a public plan.

A second important aspect concerns the list of drugs that will be covered. It is not known which list will be adopted in the context of the new law, but for provinces with less generous lists at the moment, the program will entail increased public costs. In contrast, public costs will fall if there are provinces whose current list is longer.

A third dynamic is related to changes in bargaining power. If we analyze this argument solely from the angle of drug prices, a single payer should, in theory, have more negotiating power, and so this should lead to a reduction in the bill for all medications in circulation in Canada. In practice, though, this bargaining power could be illusory, since a pan-Canadian mechanism already exists through the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance, which represents all the public provincial plans, and which already has considerable negotiating power, similar to that envisioned under a new universal public drug insurance plan.(17)

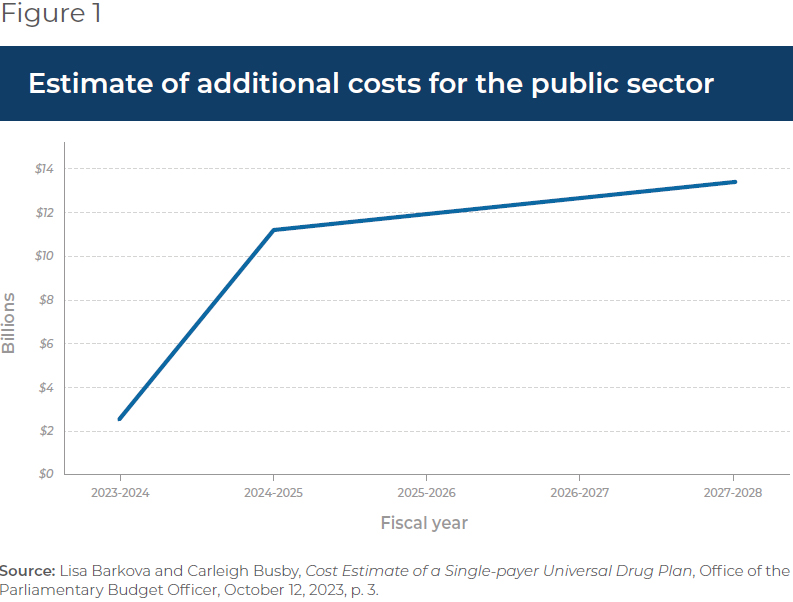

According to the calculations of the Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) in 2023, pharmacare would cost the Treasury (all levels of government combined) billions of dollars more. The PBO’s simulation, based on the hypothesis that the RAMQ’s list of drugs is adopted across Canada, and with a start date of January 1st, 2024, estimated growing additional costs in the years following program deployment, reaching over $10 billion as of the second year(18) (see Figure 1).

These additional costs will necessarily fall on taxpayers’ shoulders, in the form of taxes devoted to paying this new bill.(19)

Addressing Canadians’ Unequal Coverage

Rather than the federal government imposing the uniform transition of all insurance programs toward public programs as the NDP is suggesting, it would instead be preferable to safeguard the diversity of public and private insurance that exists at the provincial level.

If a non-negligible number of Canadians are not actively covered by a drug insurance plan, in reality, only 2.8% of Canadians, or 1.1 million people, are not eligible for any kind of drug insurance.(20) It is worth noting that this proportion has not risen; it is in fact very near to what it was at the start of the millennium.(21)

There are nonetheless 3.8 million Canadians who are not signed up(22) yet are in fact eligible for some form of public or private drug insurance.(23) In these cases, it is better to plug the gaps in the different provincial systems so that everyone has access to one form or another of insurance and is properly informed about it, rather than overturn current public and private coverage and risk adversely affecting a large proportion of Canadians.

Such a model would allow otherwise uninsurable Canadians to enjoy drug coverage, without withdrawing from the majority of Canadians their current private coverage.

In this regard, in Prince Edward Island, the provincial government came to an agreement with the federal government in 2021 for the purpose of improving drug access and affordability in the province. A variety of drugs were targeted by the program, from migraine medications to cancer treatments.(24) This is an example of a program targeting the specific needs of the province.

Another example is that of Quebec’s mixed public and private system, offering default coverage to all Quebecers, which could serve as a model for the other provinces if they so wish. The door remains open to a market for private insurance, often more generous than the public plans. In this way, market competition allows Canadians to continue to enjoy relatively more generous drug insurance, but also to be insured by the public plan in case of loss of employment.

Such a model would allow otherwise uninsurable Canadians to enjoy drug coverage, without withdrawing from the majority of Canadians their current private coverage, which is on the whole more generous. Moreover, such a solution would be less demanding fiscally, as it would have a much smaller impact on public finances than a pan-Canadian public monopoly.

Conclusion

The disastrous state of the health care systems across Canada illustrates just how bureaucratic they are. There is real paralysis when it comes to innovating and increasing efficiency.

By developing a uniform, 100% public, pan-Canadian drug insurance plan, we risk considerably reducing coverage quality for a large number of Canadians and reproducing what is happening elsewhere in the health care system, namely abusive bureaucratization where the needs of patients are of secondary importance.

References

- House of Commons of Canada, Bill C-340: An Act to enact the Canada Pharmacare Act, June 13, 2023.

- This is a condition for maintaining the March 2022 Supply and Confidence Agreement, according to which the two parties unite for key votes. Laura Osman, “Le NPD convient d’une échéance du 1er mars,” La Presse, December 14, 2023; Government of Canada, “Delivering for Canadians Now,” Press release, March 22, 2022.

- The Conference Board of Canada, “Understanding the Gap 2.0: A Pan- Canadian Analysis of Prescription Drug Insurance Coverage,” July 13, 2022, Appendix C.

- Idem.

- Each single medication is associated with a Drug Identification Number (DIN). A DIN is assigned to each brand and specific dosage of drug. Therefore, drugs of the same brand of the same compound, but of different dosages, will each have their own DIN. A generic version of the same basic compound and of the same dosage will have a different DIN from the innovative drug.

- Author’s calculations. The Conference Board of Canada, op. cit., endnote 3, Appendix F.

- Ibid., p. 4.

- This statement is based on the PBO’s hypothesis that the list of covered medications would be the same as the RAMQ’s. It also assumes that all private insurers cover a greater variety of drugs than the public insurers. Author’s calculations. The Conference Board of Canada, op. cit., endnote 3, Appendix F. Lisa Barkova and Carleigh Busby, Cost Estimate of a Single- payer Universal Drug Plan, Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer, October 12, 2023, p. 3.

- Personal correspondence with Alan Low, pharmacist and executive director of Medicines Access Coalition, January 9, 2024. Medicines Access Coalition is an advocacy group comprised of pharmacists from British Columbia who want to improve access to drugs.

- The process outlined in this Note is substantially simplified, and is meant simply to illustrate its complexity and length.

- Government of Canada, Departments and agencies, Health Canada, Drugs and health products, Drug products, February 22, 2023.

- Innovative Medicines Canada, “Increasing Access to Innovative Medicines: Pre-Budget Consultations in Advance of the 2023 Budget,” October 7, 2022, p. 3.

- Idem.

- Ibid., p. 7.

- Innovative Medicines Canada, “Addendum to Innovative Medicines Canada Submission on National Pharmacare,” June 1st, 2023, p. 1.

- Yanick Labrie, Laura Lasio, and Roxane Borgès Da Silva, Réduction des délais de négociation des nouveaux médicaments dans les provinces canadiennes : effets sur la santé et sur les dépenses publiques, CIRANO, décembre 2020, p. 6.

- Innovative Medicines Canada, op. cit., endnote 12, p. 7; Canada’s Premiers, The pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance, consulted February 13, 2024.

- As the form which the drug insurance will take remains unknown, the PBO’s projections are based on a previous plan proposed in 2016. Lisa Barkova and Carleigh Busby, op. cit., endnote 8, p. 3.

- Despite these increases in public spending, the PBO projects a general savings in total spending on drugs (private and public combined) compared to the status quo, amounting to $2.2 billion in 2027-2028, due among other things to the projected drop in existing drug prices.

- In Ontario and Newfoundland and Labrador. The Conference Board of Canada, op. cit., endnote 3, p. 4.

- Yanick Labrie, “Do We Need a Public Drug Insurance Monopoly in Canada?” MEI, Economic Note, August 2015.

- The Conference Board of Canada, op. cit., endnote 3, p. 7.

- Several factors can explain this phenomenon. People can be inadequately informed about their program eligibility, or they can be informed but not have the financial means to pay the fees associated with participation in the insurance program for which they are eligible. It is also possible for healthy people to not feel the need to enrol in an insurance plan and prefer to save the associated fees. A poll carried out in 2021 by Statistics Canada found that nearly one in ten Canadians did not fill their drug prescriptions for financial reasons. Kassandra Cortes and Leah Smith, Pharmaceutical access and use during the pandemic, Statistics Canada, November 2, 2022.

- Prince Edward Island, “Governments of Canada and Prince Edward Island continue work to improve access to medications for Island residents,” News, January 17, 2023.