Nudge: A New Way of Governing That Needs Oversight

Economic Note on the need to restrict the use of manipulative techniques in order to preserve each person’s ability to make informed decisions based on their own values and interests

There should be oversight of the government’s use of “nudges,” according to this study released by the MEI. “At the moment, Canada has no structure in place for the oversight of the use of behavioural science by governments to direct the choices of citizens,” explains Nathalie Elgrably-Lévy, senior economist at the MEI and author of the study.

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| Think tank calls for oversight on Canadian government paternalism (Western Standard, September 30, 2023)

We need to know when government is trying to alter our behaviour (Financial Post, October 6, 2023) |

Interview (in French) with Nathalie Elgrably-Lévy (Le café show, ICI Radio-Canada, October 6, 2023) |

This Economic Note was prepared by Nathalie Elgrably-Lévy, Senior Economist at the MEI. The MEI’s Regulation Series aims to examine the often unintended consequences for individuals and businesses of various laws and rules, in contrast with their stated goals.

Governments have always intervened in economic and social life. Regulation, financial incentives, information, and awareness-raising, as well as training and education, are the measures traditionally used in the deployment of public policies. Since the Second World War, and up until recently, psychological techniques were not usually part of the government toolkit, or were only anecdotally so. But the advent of behavioural science and neuroscience has offered leaders a new way to intervene.

This Economic Note explains the way in which politics can mobilize psychology and proposes a number of recommendations designed to protect fundamental rights and democracy.

A New Paradigm

In 2008, Richard Thaler, a behavioural economist, and Cass Sunstein, a legal scholar, published Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness.(1) The authors introduce the concept of the “nudge,” an innovative way to make use of the knowledge emerging from behavioural science to better understand economic decisions. They focus in particular on the way cognitive biases(2) can furtively influence individuals’ decisions and choices.

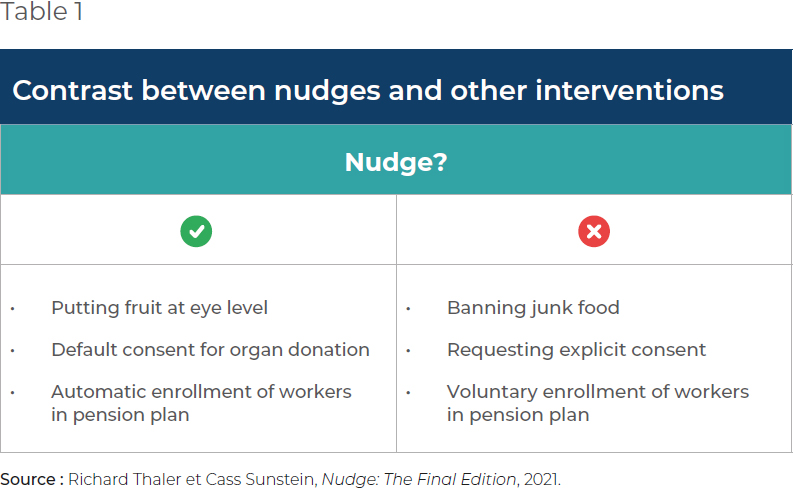

More precisely, Thaler and Sunstein define a nudge as “any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives. To count as a mere nudge, the intervention must be easy and cheap to avoid. Nudges are not taxes, fines, subsidies, bans, or mandates. Putting the fruit at eye level counts as a nudge. Banning junk food does not.”(3)

A nudge is therefore a way to instrumentalize the unconscious and emotional part of the human mind in order to guide the behaviour of individuals without their knowledge all while giving them the impression of having freedom of choice. Qualified as “libertarian paternalism” by Thaler and Sunstein, this new approach aims to increase the scope of public policy, and ultimately, to alter the configuration and functioning of society (see Table 1).

An Institutionalized Concept

The excitement surrounding the book was immediate, both in scientific circles and in the political sphere. By reinventing the way in which public policies are designed, “libertarian paternalism” was a turning point in the art of governance.

The American government, under the presidency of Barack Obama, was the first to institutionalize this new political doctrine. It recruited Cass Sunstein as of 2009 and made him Administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs.(4) In 2015, the president signed an executive order entitled “Using Behavioral Science Insights To Better Serve the American People.”(5)

A nudge is a way to guide the behaviour of individuals without their knowledge all while giving them the impression of having freedom of choice.

On the British side, Richard Thaler acted as advisor to Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron who, in 2010, inaugurated an administrative unit called the “Behavioural Insights Team”(6) (BIT) in order to introduce the teachings of behavioural science into the design of government policies.(7)

Today, a large number of countries as well as institutions like the OECD,(8) the World Bank,(9) UNICEF,(10) and the United Nations(11) have their own teams of “nudge” experts. Indeed, former UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon stated that “[i]n order to succeed, Agenda 2030 must account for behavioural insights research.”(12) Note that many international consulting firms like McKinsey & Company are also articulating their strategies around nudge principles.(13)

Canada Follows Suit

In 2015, Policy Horizons, an entity of the government of Canada, saw its mandate expanded to include the study and analysis of behavioural science.(14) And in 2017, the federal government created Impact Canada through the Privy Council Office.(15) This unit, essentially made up of behavioural science experts,(16) is dedicated to experimenting with new approaches, including the use of nudges.(17)

Among other things, Impact Canada was an important player in the orchestration of the government’s response to the pandemic. In March 2020, the unit “launched a program of applied research grounded in Behavioural Science (BeSci) to help support the Govern-ment’s response effort in accurately and effectively promoting the behaviours recommended by public health experts to reduce the spread of COVID-19 in Canada.”(18)

The Privy Council Office’s Departmental Plan 2022-23 also highlighted a reliance on behavioural science.(19) It states: “PCO will expand its use of behavioural science and advanced policy research to support the Government response to climate change, leading a large, multi-year program of work on climate action that applies insights and methods from behavioural science to promote mitigation and adaptation behaviours at both the individual and systems level.” The Departmental Plan 2023-24 states, “In addition, the behavioural science program of research will continue to be expanded and applied to address additional government priorities.”(20)

A large number of countries as well as institutions like the OECD, the World Bank, UNICEF, and the United Nations have their own teams of “nudge” experts.

In parallel to the federal initiative, the Behavioural Insights Team opened an office in Toronto in 2019.(21) It collaborates with all levels of government, municipal, provincial, and federal, as well as with non-profit organizations and foundations across Canada.

The reliance on behavioural science in general, and behavioural economics in particular, is therefore very much institutionalized throughout the government apparatus. Today, even though the administrative units that use these new technologies to reinvent public policy are not well known to the public, they are nonetheless the instigators of a new method of governance that allows government to be the architect of individuals’ behaviour.

Therefore, instead of using its traditional tools, governments strategically mobilize the unconscious and emotional processes of our cognitive systems to influence our behaviour in subtle ways without resorting to explicit restrictions. In this way, they try to elicit certain actions on the part of citizens that appear voluntary, but that can nonetheless differ from those they would otherwise have spontaneously taken. Let us call this way of governing through nudges “behavioural politics.”

Preserving Democracy

Under the rule of law, it is essential to restrict the use of manipulative techniques that influence the thoughts, emotions, and behaviours of individuals, and so to preserve each person’s individual freedom, integrity, dignity, and ability to make informed decisions based on their own values and interests. The nudges used by governments to carry out their policies should not be exempt from this imperative.

It is essential to restrict the use of manipulative techniques that influence the thoughts, emotions, and behaviours of individuals.

To be sure, it is the responsibility of governments and public bodies to act in the public interest and protect the rights and well-being of citizens. Despite the undoubtedly laudable motives behind government policies, the establishment of safeguards in their design and implementation is necessary to ensure democratic governance that respects the freedom and aspirations of all individuals.

Indeed, behavioural politics has some particularities that require regulation adapted to the issues it raises. Here are a few of these.

- Nudges exploit cognitive biases to guide the choices of individuals in the direction the government desires. Yet decision makers are themselves equally vulnerable to cognitive biases, which influence their own choices in terms of public policies.(22) They could therefore very well favour and encourage measures not aligned with the interests of the population.

- Decision makers, even setting aside their own cognitive biases, cannot be neutral. As they have a limited understanding of the values and preferences of citizens, they will tend to substitute their personal conceptions of the interests of individuals for those of the people targeted by their nudges.(23)

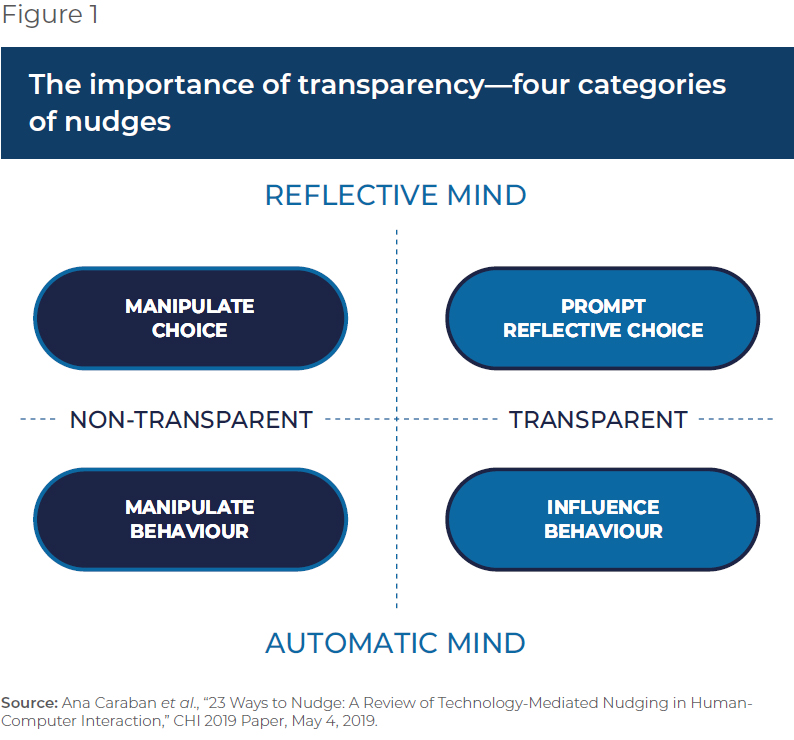

- Nudges are inconspicuous. The individuals targeted by them are generally unaware that others are taking advantage of their cognitive biases in the pursuit of some goal. This characteristic raises the issue of transparency and poses a challenge to the basic right of individuals to make free and informed decisions, and therefore with full knowledge, free from coercion or manipulation (see Figure 1).

- Nudges evade the traditional political process. As they usually consist of a subtle, if not sneaky, shifting of the target audience, they do not stem from a bill detailing the motives and provisions of the proposed policy and they are subject to no form of parliamentary debate.

- The use of nudges for political purposes raises fundamental ethical questions. There is currently no guarantee that it will never be used to manipulate public opinion for partisan purposes, to promote specific interests, or to move into areas where the government does not belong.

The adequate oversight of nudges, notably guaranteeing transparency and the political process, is essential in order to mitigate the risks of abuse and preserve democratic integrity.

Limiting the Dangers of Nudges

In order to favour the responsible use of behavioural politics in a way that is respectful of citizens, several measures can be envisioned.

– Extend the political process to nudges. Like any other law or policy, nudge measures should be subject to the traditional political process and debated before being implemented. On the one hand, this would force its instigators to publicly defend their initiative. On the other, it would allow citizens to be informed of the existence of nudges, to understand how they are used to influence their choices, and potentially, to participate in the decision-making process, including through public consultations.

– Limit, if not prohibit outright, default choices.(24) It is crucial to require an active choice between accepting or refusing the default option, in order to counteract the status quo bias, which can distort individuals’ decisions. By offering clear alternatives and not taking advantage of passivity, individuals are allowed to exercise their autonomy in a fully informed manner.

– Create an independent ombudsman position. The ombudsman would be responsible not only for overseeing the use, legality, legitimacy, and morality of nudges, but also for ensuring the respect of individuals’ fundamental rights. This measure would reinforce responsibility and accountability in the use of behavioural politics. The ombudsman’s conclusions should in turn be made public on a regular basis.

– Establish redress mechanisms. Such mechanisms would welcome citizen complaints and mandate examination committees or independent mediators to investigate concerns and propose appropriate remedial action.

– Set up an official public registry of nudges. A registry would be an effective means of reporting on the use of these behavioural policies. It would allow for the identification and documentation of each nudge put in place by detailing its objective, its modalities, and its expected effect.

– Give each nudge an expiration date. This measure would ensure that nudges are not used in permanence or for an undefined period, but that their legitimacy is regularly debated and re-evaluated. In this way, practices that could violate democratic and ethical principles would not persist.

Decision makers, even setting aside their own cognitive biases, have a limited understanding of the values and preferences of citizens.

Conclusion

Behavioural politics proposes an innovative and seductive governance paradigm. Guided by an almost surgical understanding of the human psyche, nudges allow individual choices to be directed, for good or for ill. In this context, it is essential for there to be oversight of behavioural politics so that it respects individual freedom and democracy, and does not simply offer up the illusion of freedom and democracy. The above recommendations provide a starting point to open a discussion about the use of behavioural politics, and hopefully, to inspire the construction of a solid framework to restrict nudges to uses that are responsible, ethical, and respectful of our fundamental rights.

References

- Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein, Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness, 2008.

- A cognitive bias is a way of thinking that can sometimes deceive us or lead us to make decisions based on an erroneous view of reality.

- Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein, Nudge: The Final Edition, 2021, p. 8.

- Benjamin Wallace-Wells, “Cass Sunstein Wants to Nudge Us,” The New York Times, May 13, 2010.

- U.S. Government, Executive Order 13707-Using Behavioural Science Insights To Better Serve the American People, September 15, 2015.

- The Behavioural Insights Team – BIT, “Who we are,” consulted September 10, 2023.

- Idem. The unit has offices in seven countries, including Canada.

- Observatory of Public Sector Innovation, About us, Empowering governments to achieve new possibilities, consulted September 10, 2023.

- World Bank, Mind, Behavior and Development Unit, eMBeD uses behavioral sciences to fight global poverty and reduce inequality, consulted September 10, 2023.

- UNICEF, BirdLab, Behavioural Insights, Research and Design Laboratory, consulted September 10, 2023.

- United Nations Development Program, “Behavioural Insights at the United Nations – Achieving Agenda 2030,” December 20, 2016.

- Idem.

- McKinsey & Company, “Behavioral science in business: Nudging, debiasing, and managing the irrational mind,” February 18, 2018.

- Government of Canada, Policy Horizons Canada, About Us, consulted September 10, 2023.

- Government of Canada, Building a Strong Middle Class, #Budget2017, March 22, 2017, p. 81.

- Government of Canada, Impact Canada, Our people, consulted September 10, 2023.

- Impact Canada, “Experimentation direction for Deputy Heads – December 2016,” Government of Canada, June 8, 2017.

- Government of Canada, Impact Canada, Applying BeSci to the COVID-19 Response, consulted September 10, 2023.

- Government of Canada, “Departmental Plan 2022-23,” March 3, 2022.

- Government of Canada, “Departmental Plan 2023-24,” March 9, 2023.

- The Behavioural Insights Team, Canada, consulted September 10, 2023.

- Among others, there is the blind spot bias, which is the tendency of individuals to recognize the existence of cognitive biases in others, but to underestimate or ignore their own propensity to be influenced by such biases.

- For example, Thaler and Sunstein suggested modifying the architecture of choice in order to trick workers into saving for retirement without taking into account that some people might have more urgent, and no less important, needs to satisfy. Along the same lines, it would be possible to trick individuals into consuming more when it was in their interests to save or invest.

- For example, in the field of health care, the default choice can be to automatically sign everyone up for organ donation, unless a person actively decides to deregister.