Increase Productivity to Respond to the Labour Shortage

Economic Note proposing effective ways to circumvent the labour scarcity problem and ensure economic prosperity

In order to alleviate the lack of labour, the Quebec government should lower corporate taxes, which would stimulate investment in productivity, according to this study published by the Montreal Economic Institute.

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| Pénurie de main-d’œuvre: augmenter la productivité comme piste de solution (Le Journal de Québec, January 31, 2023)

To alleviate Quebec’s labour shortage, boost productivity (Montreal Gazette, February 1st, 2023) MEI economist says lower taxes would raise productivity and aid labour shortage (The Suburban, February 4, 2023) |

This Economic Note was prepared by Nathalie Elgrably-Lévy, Senior Economist at the MEI, in collaboration with Renaud Brossard, Senior Director, Communications at the MEI. The MEI’s Taxation Series aims to shine a light on the fiscal policies of governments and to study their effect on economic growth and the standard of living of citizens.

The labour shortage is undoubtedly among the biggest challenges currently facing Quebec businesses. Every sector of economic activity must now contend with labour scarcity, and employers are having to redouble their effort and imagination in order to attract and retain employees. This Economic Note exhorts the reader to transcend the usual solutions revolving around recruitment and to look instead at productivity increases and tax relief as effective ways to circumvent the labour shortage problem and, ultimately, ensure economic prosperity.

Job Vacancies Have Doubled Since the Start of the Pandemic

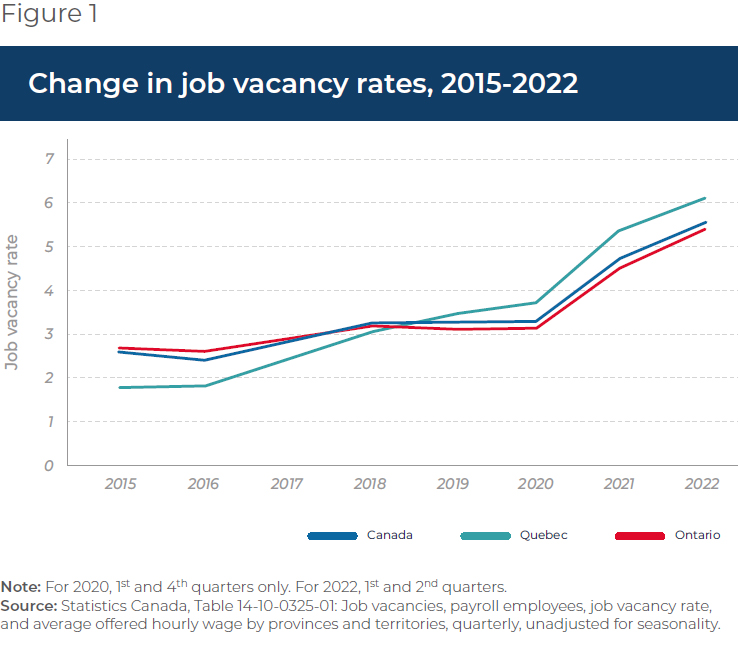

Labour scarcity is not just a recent phenomenon, as the job vacancy rate in Quebec almost doubled between 2015 and 2019, increasing from 1.8% to 3.45% (see Figure 1). However, in the wake of the pandemic, it has swollen to unexpected and troublesome proportions.

The most recent data from Statistics Canada indicate that in the third quarter of 2022, there were nearly one million job vacancies in Canada, including 246,230 in Quebec. This corresponds to a provincial job vacancy rate of 6.41%, which is double that of the first quarter of 2019. The Department of Labour, Employment, and Social Solidarity had estimated that the province would need to fill 1.4 million positions from 2017 to 2026.(1) Moreover, due to ongoing demographic aging, it is legitimate to expect labour scarcity to continue to worsen over the next decade and beyond.

Labour shortages cause a considerable loss of earnings for companies and, in turn, for society as a whole. Among other things, in 2021-2022 the lack of personnel cost Quebec SMEs to lose sales contracts worth approximately $11 billion.(2) The manufacturing sector also reports having been forced to forego nearly $18 billion in revenue over the past two years,(3) for the same reasons. Sacrificing business opportunities means slowing economic growth, therefore limiting potential increases in standard of living for all Quebecers.

Labour shortages cause a considerable loss of earnings for companies and, in turn, for society as a whole.

The solutions proposed are numerous: increasing immigration thresholds, facilitating the hiring of temporary foreign workers, encouraging the return of retirees to the labour market, raising the retirement age, adding childcare spots, offering subsidies to companies to help them improve wages, etc.

Finding ways to fill jobs was a central issue in the last provincial election campaign. For example, to encourage retirees to return to the workforce, the Quebec Liberal Party proposed increasing the tax exemption for workers over 65 from $15,000 to $30,000.(4) For its part, the Parti Québécois promised tax rebates for those aged 60 and over and committed to suspending contributions to the Quebec Pension Plan for those aged 65 and over.(5)

The above solutions may have some merit. If applied correctly and precisely, they have the potential to help provide jobs and boost production. On the other hand, history has shown that the enrichment of societies does not depend solely on the expansion of their labour pool. If this were the case, the most populous countries would also be the most prosperous. But this is not what we observe. To take advantage of every opportunity for economic development, we must therefore stop depending solely on recruitment. There are other means of overcoming labour shortages and ensuring economic prosperity.

The Determinants of Economic Growth

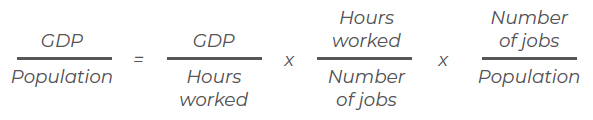

In order to prioritize the policies that promote the growth of our standard of living, we must first identify what determines living standards. The equation below presents the three variables used to calculate the level of wealth per person:

Thus, the standard of living (GDP/population) depends on the productivity of workers (GDP/hours worked), the work intensity (hours worked/number of jobs) and the employment rate (proportion of the population that is employed). In theory, an increase in any of these three variables, all else being equal, will enrich society. But in practice, not all levers of growth are equivalent.

For example, work intensity has been declining for over a century, and it is unlikely to increase significantly in the future. Moreover, it is a so-called “bounded” variable, because even if it does increase, it will quickly reach an upper limit that is difficult, if not impossible, to exceed.

As for the employment rate, although it has increased over the past fifty years, it too represents a “bounded” variable, as there will always be a fraction of the population unavailable for employment.

To ensure economic growth that is stable and sustainable, and therefore relatively resistant to labour shortages, it is necessary to rely on an unbounded variable whose effectiveness has been confirmed: the ratio of GDP to hours worked, i.e., worker productivity. This is an important variable because it measures how efficiently a worker uses their time to produce goods and services. As one might expect, a worker who produces three units per hour contributes more to a society’s standard of living than two workers who each produce only one unit per hour.

The value of productivity is therefore based on a simple principle: fewer workers who produce a lot are better than many workers who produce relatively less. The efficiency of workers is more important than the number.

If workers are scarce, then we must increase the productivity of the workers who are available.

Furthermore, in contrast with other levers of growth, productivity has no insurmountable upper limit. As long as certain conditions are met, it can increase indefinitely, as its evolution since the Industrial Revolution has demonstrated.

Thus, since increases in productivity are recognized as the main vehicle for long-term wealth creation, they should be considered a powerful solution to the current labour shortage. In other words, if workers are scarce and there is not enough labour, then we must increase the productivity of the workers who are available.

Quebec’s Productivity Is Lagging

In terms of productivity, Quebec is not doing well. Since 1997, it has trailed significantly behind Ontario, Alberta, and the Canadian average (see Figure 2). Note that the gap with Alberta has narrowed very modestly, while with Ontario and Canada as a whole it has widened. The reader will remark a substantial drop in 2020 due to the pandemic and the attendant lockdown measures.

Today, Quebec’s productivity sits at 88.6% of that of Canada as a whole, 91.8% that of Ontario, and just 67.2% that of Alberta. If the current average annual growth rate of Canadian productivity (1.19%) were to persist, Quebec’s productivity would have to increase at an average annual rate of 2.42% to catch up to the national level in a decade. This is more than double the province’s current rate of 1.1%.

It should be emphasized that this productivity gap is not unique to the last quarter century. On the contrary, Quebec has been bringing up the rear since Canadian Confederation began.(6)

According to one study,(7) the productivity gap between Quebec and the average of 19 OECD countries(8) has widened considerably since 1981. The researchers state that “the entire gap in living standards between Quebec and the OECD19 average is now explained by the relative weakness of the province’s productivity. […] Productivity will therefore be the only lever available to the province to support the growth of its economy.”

Closing the productivity gap is not an impossible challenge. But it does require public policies that provide the right incentives.

Labour Shortage: Tax Policy to the Rescue

For many years, public administrations, policymakers and companies were all operating in a context of high unemployment. Measures and programs aimed at job creation were thus proposed. However, the current scarcity of labour requires a paradigm shift. In order to sustain production activities in the context of a labour shortage, it has now become imperative to direct public policy toward productivity gains rather than toward recruitment.

Since productivity gains result from the modernization of production techniques, they require effort on two levels. They clearly need sustained investment in cutting-edge technologies, machinery, manufacturing and processing equipment, infrastructure, and intellectual property. But they also rely on process and product innovations. Since such initiatives obviously come with a price tag, the question of financing becomes a matter for consideration.

Tackling the labour shortage therefore requires the creation of an environment favourable to investment and research and development activities. With this in mind, it is important for the government to re-evaluate its support system to align it with the realities of the economic situation and the needs of business. In order to increase companies’ financial room for manoeuvre, consideration should be given to reducing the tax burden, in particular through reductions in corporate taxes.

Consideration should be given to reducing the tax burden, in particular through reductions in corporate taxes.

Empirical research has established the existence of an inverse relationship between corporate taxation and levels of investment and entrepreneurship. In particular, a study of 85 countries, including developing countries, found a “consistent and large adverse effect of corporate taxes on both investment and entrepreneurship.”(9) A 2019 study also confirmed the depressive impact of corporate taxes on investment and productivity and, ultimately, on economic growth.(10) Another study published in 2022 concluded that corporate tax cuts lead to sustained increases in GDP and productivity, with a maximum effect after five to eight years.(11)

For the sake of intellectual integrity, it must also be noted that there exist studies that do not support the positive impact of corporate tax cuts. As it happens, one 2021 study concluded that making changes to corporate taxes has no statistically significant effect on economic growth. However, such results remain marginal in the literature.(12)

This is the logic behind an effort to reduce the tax burden, as the funds not taken by the state would provide companies with the flexibility to acquire productive capital. The resulting increases in productivity would then allow companies to offer workers higher wages or better working conditions, without relying on government subsidies. It should also be noted that this reduction in the tax burden will have the collateral benefit of allowing companies to improve their competitiveness in external markets, which will further contribute to the growth in standard of living.

In order to overcome the constraints imposed by labour shortages, the government should be exploring options for increasing the efficiency of public spending, particularly via targeting of growth-generating activities rather than by hiring workers. While the Quebec government claims that it wants to encourage businesses to focus on productivity gains, one study found that fiscal policy “has remained firmly focused on employment even as pressure on the labour market has been increasing.”(13) In the current context, therefore, it has become appropriate to transform payroll-based tax credits into tax credits that promote investment and innovation.

Conclusion

The labour market is under considerable pressure. In addition to measures that promote expansion of the labour pool, it is now more important than ever to focus on achieving gains in productivity as well. This approach is all the more crucial given that Quebec is lagging badly in productivity, which is undermining growth in its citizens’ standard of living. Since these productivity gains necessarily involve investment and innovation, public policies must be designed and implemented with a view to promoting these variables. However, the policies currently in force date from a period when unemployment dominated the economy. Now that the situation has changed so completely, public policy needs to be redesigned to ease the tax burden on businesses, for instance, by lowering corporate income taxes. And the sooner the better!

References

- Department of Labour, Employment, and Social Solidarity, “En action pour la main-d’œuvre,” Government of Quebec, 2019.

- Laure-Anna Bomal, “Financial Impact of Labour Shortages in Quebec: Estimated revenue losses incurred by small businesses in the last year,” Canadian Federation of Independent Business, August 2022, p. 3.

- Véronique Proulx, “Les manufacturiers sous pression,” Manufacturiers et Exportateurs du Québec, June 29, 2022.

- Nicolas Lachance, “Pénurie de main-d’œuvre: le PLQ promet 500 M$ pour convaincre les personnes plus âgées à retourner sur le marché du travail,” Le Journal de Québec, September 3, 2022.

- Fanny Lévesque, “Le PQ veut ramener 150 000 travailleurs expérimentés à l’emploi,” La Presse, September 7, 2022.

- Vincent Geloso, Une perspective historique sur la productivité et le niveau de vie des Québécois : de 1870 à nos jours, Centre for Productivity and Prosperity, HEC Montréal, September 2013, p. 3.

- Jonathan Deslauriers, Robert Gagné and Jonathan Paré, Productivity and Prosperity in Quebec – 2021 Overview, Centre for Productivity and Prosperity – Walter J. Somers Foundation, HEC Montréal, March 2022, p. 13. Author’s translation.

- Given the exceptional performance of the Irish economy, researchers at the Centre for Productivity and Prosperity chose to exclude Ireland from the 20 OECD countries they evaluated previously.

- Simeon Djankov et al., “The Effect of Corporate Taxes on Investment and Entrepreneurship,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, Vol. 2, No. 3, July 2010, p. 33.

- Ergete Ferede and Bev Dahlby, The Effect of Corporate Income Tax on the Economic Growth Rates of the Canadian Provinces, The School of Public Policy, University of Calgary, September 2019, p. 4.

- James Cloyne et al., Short Term Tax Cuts, Long Term Stimulus, NBER, Working Paper 30246, July 2022. p. 1.

- Sebastian Gechert and Philipp Heimberger, Do Corporate Tax Cuts Boost Economic Growth? The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, Working Paper 201, June 2021, p. 30.

- Jonathan Deslauriers, Robert Gagné and Jonathan Paré, op. cit., endnote 8, p. 5. Author’s translation.