Improving Schooling Outcomes: It’s about Choice, Not Spending More

Economic Note showing that policies that expand parental choice and school autonomy can lead to improved cognitive and non-cognitive outcomes for students

With students across Canada preparing to go back to school, the MEI released this study on how to improve educational outcomes. Vincent Geloso, Senior Economist at the MEI, concludes that it is an illusion to think that the quality of education will be improved merely by increasing government spending.

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| Amélioration des résultats en éducation au Québec: il faut plus de choix et d’autonomie (Le Journal de Montréal, August 18, 2022)

Canada needs school choice (Financial Post, August 23, 2022) Less spending, better choices needed to help students: MEI study (The Suburban, August 24, 2022) |

Interview (in French) with Vincent Geloso (Midi Pile, 95,7 KYK, August 18, 2022) |

This Economic Note was prepared by Vincent Geloso, assistant professor of economics at George Mason University and Senior Economist at the MEI. The MEI’s Education Series aims to explore the extent to which greater institutional autonomy and freedom of choice for students and parents lead to improvements in the quality of educational services.

In the latest provincial budget, we learned that six in ten schools in Quebec are in poor physical condition. This prompted the government to announce a new round of investments to remedy the situation.(1) However, similar “crises” have erupted on multiple occasions in recent decades: disappointing performance on standardized tests, low completion rates, violence in schools, lack of preparedness for post-secondary studies, etc. Each of these crises prompted political actors to request further rounds of investments, reinvestment, new investments, refinancing, or improved financing. In other words, the conversation always revolves around securing improvements in educational outcomes by increasing the quantity of inputs used.

Increasing the resources devoted to the provision of education, however, sidesteps the crucial issue of how resources are used in the first place. The reality is that Quebec could gain immensely by downsizing the activities of the department of education (notably by reducing administrative staff), reallocating school funding so that parental choices determine where taxpayer funds go, and introducing greater school autonomy. This will likely lead to reduced government expenditures, as well as improved cognitive and non-cognitive outcomes for students.

Spending Levels Are Poor Predictors of Performance

There exists a large empirical literature, looking at both historical and contemporary cases, documenting the weak relationship between input levels and educational performance.(2) At best, the relationship shows a weak positive impact such that only very large sums per pupil produce additional benefits.(3) That small effect is also highly conditional on the type of spending (for example, buildings and staff vs. child-oriented materials).(4) At worst, the effect can actually be counterproductive under certain conditions.(5) This finding, which is widespread in American and international studies, is borne out by Quebec data showing that performance on PISA tests for mathematics appears to have been quite stable (-1.5%) since 2006 even though spending per pupil has increased substantially (+18%) (see Figure 1).

This is consistent with standard economic theory, which holds that it is not only the quantity of inputs thrown at the provision of a good or service that matters; the way in which the service is provided matters just as much, if not more. In other words, the organizational structure of the system is very important. Moreover, as the literature clearly shows, systems that decentralize management to the local level, introduce choice and exit options for parents, and create local voicing mechanisms (such as participating in schooling associations) heighten the efficiency of any given spending level.(6) Generally, such systems work by having the state disengage from producing the service and concentrate solely on financing, which is also tied to parental choices.

There are three key reasons that explain these results. First, there are wide variations in the socio-economic characteristics of children even at the local level. As a rule, “one-size-fits-all” policies tend to yield disappointing outcomes for such heterogenous populations. Greater decentralization and school autonomy, on the other hand, allow for customization such that schools can organize the resources they obtain in ways that are most productive given the specific populations they serve. Second, parental involvement tends to be higher in decentralized systems, and this creates a positive feedback loop between school administrators and local populations, which helps improve customization. Third, tying funding to parental choices gives parents an exit option, which in turn generates strong incentives for schools to provide higher-quality customization.

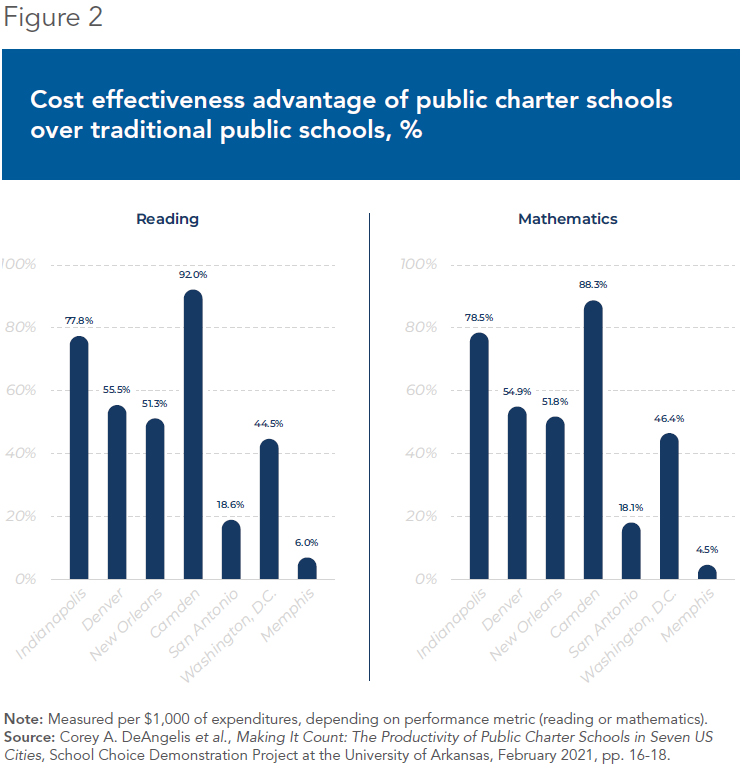

In other words, it is possible to reduce educational spending while still improving outcomes by changing the organizational structure of the educational system. The American literature on the cost-effectiveness of charter schools provides a good empirical illustration of this. While US charter schools are publicly funded, they are given greater autonomy than traditional public schools in exchange for meeting certain performance criteria. One recent study compared cost-effectiveness across seven major American cities and found that $1,000 of public spending secured schooling performance that was from 4.5% to 92.0% higher in charter schools than in traditional public schools (see Figure 2). This cost-effectiveness advantage, echoing the findings of many peer-reviewed articles,(7) is attributable to the flexibility afforded by greater autonomy, which allows methods to be adjusted to local communities.

Cognitive and Non-Cognitive Outcomes

The benefits of this customization, which go beyond mere cost-effectiveness, are quite considerable, and fall into two categories: cognitive outcomes (namely, performance on test scores) and non-cognitive outcomes.

With regard to cognitive outcomes, the literature is quite robust, as it relies on randomized control trials (RCTs). RCTs are well regarded in the economics profession because they recreate experimental conditions so as to directly assess the causal effect of a given treatment—in our case, the introduction of parental choice and school autonomy. The “randomized” part refers in this case to the fact that parents get to exercise choice if they participate in a lottery system that allows some of them to send their children to other publicly-funded schools or receive school-vouchers. Because the lottery is random, we can compare the effect on children who were selected and those who were not in a manner that allows statements about the causal effects of parental choice and school autonomy.

The majority of RCTs testing increases in parental choice find a clear positive effect on cognitive outcomes. Indeed, 10 of the 17 RCTs found statistically significant gains on mathematical and reading scores, 4 found no effects, 1 found mixed effects, and 2 found adverse effects.(8) Moreover, the two studies that found adverse effects concerned cases where the gains in school autonomy and parental choice were small compared to other cases studied in the literature.(9) As such, it is quite clear that meaningful increases in parental choice and school autonomy tend to yield positive outcomes in terms of performance.

Yet cognitive benefits do not constitute the lion’s share of the benefits of parental choice and school autonomy. For parents, schooling is not only about scores on standardized tests for reading and mathematical abilities. They also consider the social environment in which their children will learn and whether it will be beneficial to their mental well-being. When parents exhibit strong preferences for mental health components of schooling, offering a greater space for school choice allows them to find a more balanced service. And indeed, the literature on parental choice in schooling shows a strong association with improvements in students’ mental health.

One recent study compared differences in trends of mental health outcomes before and after the introduction of school choice in some American states relative to differences in trends for states that did not introduce school choice.(10) This methodology, widely used in economic analysis, allows researchers to assign a causal weight to the effects they find.(11) Concentrating on teenagers between 15 and 19 years of age, the authors found a 10% reduction in suicide rates following the introduction of school choice.(12)

When they extended their analysis to other data, such as the percentage of children reporting mental health problems (for example, anorexia or bulimia), they found similar beneficial effects. The likelihood of suffering from emotional problems was reduced by between 1.9 and 2.9 percentage points(13)—a substantial proportion given that 3% of the population studied reported such problems.(14) This key result complements earlier but less robust studies connecting school choice to mental health.(15) According to the authors, this was due to the fact that schools became more sensitive to the topics of bullying, extra-curricular activities, and civic engagement. As a result, they adjusted their services to suit their local communities and create a more favourable school culture.

While most people appreciate the benefits of cognitive improvements, whose implications are intuitive, the benefits of non-cognitive improvements are harder to grasp. However, this does not mean that non-cognitive improvements have minimal value. In fact, they probably rival cognitive development in importance, as mental health in early adolescence is known to be a strong predictor of later life abilities in work environments as well as later life incomes.(16)

The problem of bullying is probably the best example of the importance of these benefits. Being bullied between the ages of 13 and 16 reduces educational achievements and earnings by age 25 by significant margins.(17) As school choice appears to create incentives for schools to reduce bullying, the benefits of this policy will only appear with some latency, but will nonetheless be considerable in the long run.

Conclusion

All sides agree that improving cognitive and non-cognitive outcomes for children is important, and that educational policy plays a significant role. However, the idea that increasing government expenditures on education will secure those improvements is misleading. The manner in which money is spent weighs more heavily than the level of spending. The bulk of the empirical literature in the economics of education suggests that policies that improve parental choice and school autonomy provide better ways to spend. The only question is how to adapt school choice and autonomy to Quebec’s particular circumstances, for the benefit of parents and students across the province.

References

- Marie-Eve Morasse, “L’état des écoles se détériore,” La Presse, March 22, 2022.

- Eric A. Hanushek, “The failure of input-based schooling policies,” The Economic Journal, Vol. 113, No. 485, February 2003, pp. F64-F98; Eric A. Hanushek, “Assessing the effects of school resources on student performance: An update,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, Vol. 19, No. 2, June 1997, pp. 141-164; Eric A. Hanushek, “The impact of differential expenditures on school performance,” Educational Researcher, Vol. 18, No. 4, May 1989, pp. 45-62; Eric A. Hanushek, Making Schools Work: Improving Performance and Controlling Costs, Brookings Institution Press, 1994; E. G. West, Education and the Industrial Revolution, Liberty Fund, 1975; E. G. West, Education & The State: A Study in Political Economy, Liberty Fund, 1994.

- C. Kirabo Jackson and Claire Mackevicius, The distribution of school spending impacts (No. w28517), National Bureau of Economic Research, July 2021.

- E. Jason Baron, “School spending and student outcomes: Evidence from revenue limit elections in Wisconsin,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, Vol. 14, No. 1, February 2022, pp. 1-39.

- Desire Kedagni et al., “Does class size matter? How, and at what cost?” European Economic Review, Vol. 133, April 2021, p. 19; Eric A. Hanushek, “Education production functions,” The Economics of Education, 2020, pp. 161-170.

- Laura López-Torres et al. “The effects of competition and collaboration on efficiency in the UK independent school sector,” Economic Modelling, Vol. 96, March 2021, pp. 40-53; Luis Gonzalez and Brandon C. Koford, “Impact of Parental Resources on Student Outcomes Using Elementary School Data,” International Advances in Economic Research, Vol. 25, No. 4, December 2019, pp. 417-427; Levon Barseghyan, Damon Clark, and Stephen Coate, “Peer preferences, school competition, and the effects of public-school choice,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, Vol. 11, No. 4, November 2019, pp. 124-58; Eric A. Hanushek and Steven G. Rivkin, Does Public School Competition Affect Teacher Quality? National Bureau of Economic Research, 2003, pp. 23-48; Steve Bradley, Geraint Johnes, and Jim Millington, “The effect of competition on the efficiency of secondary schools in England,” European Journal of Operational Research, Vol. 135, No.3, December 2001, pp. 545-568; Patrick J. Wolf and Michael McShane, “Is the juice worth the squeeze? A benefit/cost analysis of the District of Columbia opportunity scholarship program,” Education Finance and Policy, Vol. 8, No. 1, January 2013, pp. 74-99; Daniel L. Millimet and Trevor Collier, “Efficiency in public schools: Does competition matter?” Journal of Econometrics, Vol. 145, Nos. 1-2, May 2008, pp. 134-157.

- Corey A. DeAngelis, “The cost-effectiveness of public and private schools of choice in Wisconsin,” Journal of School Choice, Vol. 15, No. 2, 2021, pp. 225-247; Martin F. Lueken, “The fiscal effects of tax-credit scholarship programs in the United States,” Journal of School Choice, Vol. 12, No. 2, April 2018, pp. 181-215; Patrick J. Wolf and Michael McShane, op. cit., endnote 6; Michael R. Ford and Fredrik O. Andersson, “Determinants of organizational performance in a reinventing government setting: evidence from the Milwaukee school voucher programme,” Public Management Review, Vol. 19, No. 10, March 2017, pp. 1519-1537.

- Andrew D. Catt et al., The New 123s of School Choice: What the Research Says about Private School Choice Programs in America, EdChoice, April 2021, p. 12; see also Corey A. DeAngelis and Heidi Holmes Erickson, “What leads to successful school choice programs: A review of the theories and evidence,” Cato Journal, Vol. 38, No. 1, December 2018, pp. 247-263.

- Yuije Sude, Corey A. DeAngelis, and Patrick J. Wolf, “Supplying choice: An analysis of school participation decisions in voucher programs in Washington, DC, Indiana, and Louisiana,” Journal of School Choice, Vol. 12, No. 1, 2018, pp. 8-33; Corey A. DeAngelis, Lindsey M. Burke, and Patrick J. Wolf, “The effects of regulations on private school choice program participation: Experimental evidence from Florida,” Social Science Quarterly, Vol. 100, No. 6, July 2019, pp. 2316-2336.

- Corey A. DeAngelis and Angela K. Dills, “The effects of school choice on mental health,” School Effectiveness and School Improvement, Vol. 32, No. 2, December 2020, pp. 326-344.

- Michael A. Bailey, Real Econometrics: The right tools to answer important questions, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017; Joshua Angrist and Jörn-Steffen Pischke, Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion, Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009, pp. 221-247.

- Corey A. DeAngelis and Angela K. Dills, op. cit., endnote 10, p. 334.

- Ibid., p. 339.

- Ibid., p. 336.

- Corey A. DeAngelis and Martin F. Lueken, “School sector and climate: An analysis of K–12 safety policies and school climates in Indiana,” Social Science Quarterly, Vol. 101, No. 1, October 2019, pp. 376-405; Corey A. DeAngelis, “Does Private Schooling Affect Noncognitive Skills? International Evidence Based on Test and Survey Effort on PISA,” Social Science Quarterly, Vol. 100, No. 6, July 2019, pp. 2256-2276; Jude Schwalbach and Corey A. DeAngelis, “School sector and school safety: a review of the evidence,” Educational Review, Vol. 74, No. 4, September 2020, pp. 1-17.

- Jessica Kansky, Joseph Allen, and Ed Diener, “Early adolescent affect predicts later life outcomes,” Applied Psychology: Health & Well-Being, Vol. 8, No. 2, April 2016, pp. 192-212; David Fergusson, Joseph Boden, and John Horwood, “Recurrence of major depression in adolescence and early adulthood, and later mental health, educational and economic outcomes,” British Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 191, No. 4, October 2007, pp. 335-342; Alissa Goodman, Robert Joyce, and James Smith, “The long shadow cast by childhood physical and mental problems on adult life,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, Vol. 108, No. 15, March 2011, pp. 6032-6037.

- Emma Gorman et al., The Causal Effects of Adolescent School Bullying Victimisation on Later-Life Outcomes, Bonn, Germany: IZA-Institute of Labor Economics, May 2019, p. 41.