Improving Access to Health Data in Quebec

Economic Note showing that Quebec needs to bring its health data system into the 21st century, both to better serve patients today and to facilitate research that will benefit them tomorrow

It is hard to believe that in 2022, health data is still being communicated between institutions and departments via fax in Quebec. According to this MEI publication, Quebec’s current system does not allow for an efficient flow of information that would benefit patients, and existing electronic health records lack vital information physicians need to make a proper treatment plan.

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| Les données doivent suivre le patient (Le Soleil, June 9, 2022)

To improve Quebec’s outdated health records systems, the data must follow the patient (The Hub, June 15, 2022) |

Interview with Maria Lily Shaw (The Elias Makos Show, CJAD-AM, June 10, 2022) |

This Economic Note was prepared by Maria Lily Shaw, Economist at the MEI, and Krystle Wittevrongel, Public Policy Analyst at the MEI. The MEI’s Health Policy Series aims to examine the extent to which freedom of choice and entrepreneurship lead to improvements in the quality and efficiency of health care services for all patients.

The weaknesses in Quebec’s health care system have been laid bare by the COVID-19 pandemic. Structural problems that have existed for decades, such as the meagre number of ICU beds and other limited health care resources, were exacerbated, while issues that had been lurking under the surface, like the disjointed and inconstant technological state of the system, were exposed.

In fact, when health authorities urgently needed real-time data on the number of COVID cases in their facilities, or in the population, that information was still being communicated between institutions and departments via fax.(1) This resulted in delayed contact tracing and undoubtedly increased pressure on an already overheating system. Yet this episode has finally led to the fast-tracking of a plan to implement a long-discussed electronic system.(2) Indeed, substantial efforts have now been deployed, although an immense amount of improvement is still needed. More precisely, reforms of the collection, storage, and accessibility of health data are required, both to better serve patients today and to facilitate research that will benefit them tomorrow.

The Current Situation Is Messy

The first Quebec government initiative to introduce electronic health records (EHRs) was the 2006 Dossier Santé Québec (DSQ) project.(3) The objective of the DSQ initiative was to institute an EHR through which laboratory results, diagnostic imaging, and the list of medications already prescribed would be accessible, at the point of contact, to both doctor and patient.(4) The project had an initial budget of $563 million, but as of 2021 had actually cost Quebecers nearly $2 billion.(5) In addition, while it was meant to be completed by 2010, it has never been fully implemented.(6)

While Quebec’s current EHR system does, in theory, store test results, laboratory results, medication history, and radiology scans, patients at times still have to bring test results themselves to a doctor or repeat their entire medical history to a new physician due to a lack of interoperability between systems.(7) Interoperable EHRs are a valuable tool for health system functioning, serving as a longitudinal summary of key health events,(8) which is to say, one that follows the patient over time.

In Quebec, it is sometimes impossible for a hospital-based doctor to gain access to the medical file of a patient who previously received care in a different health care setting, such as a family medicine clinic, a long-term care centre, or another hospital. As a result, doctors are forced to waste valuable (and expensive) time following a paper trail to try and glean any information they can on their patient, playing detective to uncover pieces of what is generally a mountain of information.(9)

This has a considerable impact on the patient. Due to the fact that health care in Quebec is organized into first, second, third, and fourth lines of care and services, it is common for a patient to be monitored on the front line in one region, undergo surgery in another, and receive specialized treatments in yet a third region over an extended period of time.(10) The lack of communication between the systems used in these different facilities increases the chances that vital information will be lost in the treatment process. This can result in the patient undergoing unnecessary repeat testing, for instance, an enervating event for the patient and an expensive one for the system. This is not uncommon, especially in oncology and pediatrics.(11) Moreover, in cases of prior trauma, the repetition of medical information can lead to a re-traumatization of the patient.(12)

Interoperable EHRs can avoid such financial and psychological costs. They have also been shown to reduce hospital admissions, and the cost of emergency care.(13) Thus, the current state of affairs has a negative impact on the quality and continuity of care, both from a patient perspective and a system perspective.

Far from enhancing data accessibility, the DSQ project resulted in a fragmented system of health data collection, now scattered across 9,000 different electronic platforms, most of which are unable to communicate with one another.(14) In fact, a whole range of information is still shared by fax or CD,(15) or is only available on paper.(16) The systems in place exist solely to collect data, but do not seem to be designed to contribute to the flow of information required to carry out the primary mission of EHRs, namely to enhance the quality of patient care.

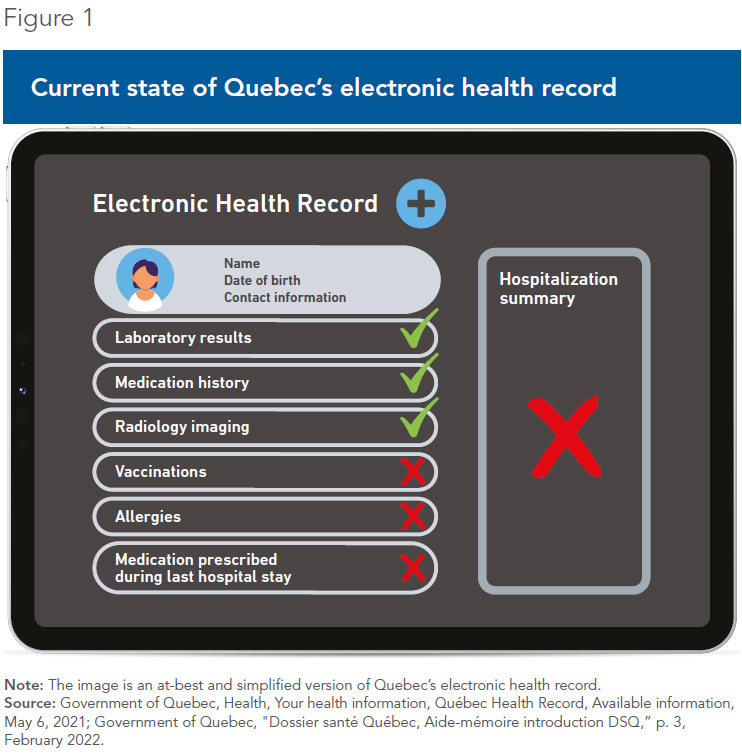

Aside from laboratory results and medications, Quebec’s existing electronic health records still lack vital information such as past or recent vaccinations, allergies, and the hospitalization summary sheet written by the attending physician after a hospital stay(17) (see Figure 1). All of these pieces of data are key elements of a patient’s health record and are vital for determining the best treatment options available. In addition to these missing elements, there are few public facilities that input medications delivered during a hospital stay into the EHR.(18) This lack of communication increases the risk of miscommunication and puts patients at risk of a negative drug reaction or interaction, or other adverse drug event.(19)

Further development of the DSQ project has since been suspended and will be replaced by the Dossier Santé Numérique (DSN) initiative, which is still in the early stages of development and comes with an estimated price tag of approximately $3 billion.(20) The DSN project is somewhat more ambitious than its predecessor, with one of its main objectives being to introduce a single platform through which patients across the province can book an appointment with a medical professional.(21) This is a functionality that has existed for several years in countries that have adopted and optimized the use of EHRs, such as Denmark, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.(22)

In essence, health data in Quebec is incomplete, fragmented, and does not follow the patient. Quebec health officials should look for inspiration to other provinces that have excelled in the area of health data collection, such as Alberta, which has become an international reference for electronic health records.

Alberta Netcare Portal (ANP)

Alberta was the first province in Canada to develop an interoperable EHR, the Alberta Netcare Portal (ANP), in 1999.(23) The ANP contains key information related to prescription drugs and drug alerts (including medications prescribed and filled as well as notifications of potential interactions of a new drug with current or recent medications), publicly-funded laboratory results, diagnostic imaging results and reports (including x-rays, CT scans, MRIs, and ultrasounds), hospital visits, surgeries, allergies and intolerances, and a record of immunizations.(24)

Prior to Netcare, a patient visiting a medical facility would require the gathering of records from other health sites by phone, fax, and mail(25)—similar to the situation that still prevails in Quebec. Since the implementation of Netcare, instead of contacting each site to obtain copies of records, a simple login to ANP will provide a health professional with all the key information needed to make decisions and determine the best course of treatment.(26) In one survey, 76% of ANP users found that it aided in the provision of quality patient care.(27)

Alberta Netcare is not a single database. According to the Government of Alberta, clinical data is collected in hospitals, laboratories, testing facilities, pharmacies, and clinics. It is then securely sent to over 50 provincial repositories and information systems. When a health professional logs on to Alberta Netcare to search for a patient record, the portal retrieves all the available information from the different systems and presents it as a single unified patient record.(28)

There is also an online tool called MyHealth Records which provides Alberta residents with access to select information from Netcare including medications dispensed, immunizations, and results of laboratory tests, as well as allowing users to enter and track their own health information such as blood pressure, blood glucose levels, and other metrics.(29) Providing patients with access to their own health data has resulted in improved patient-provider interactions, and increased patients’ knowledge of their own health and the impact of treatments and preventive care.(30)

Canadian survey data shows that interoperable EHRs are perceived as positively impacting quality of care and productivity.(31) Ultimately, the ANP increases the efficiency of the health system by presenting health care providers with immediate access to unified and comprehensive electronic health records for individual patients.(32)

Making Health Data Accessible to Researchers

Beyond the obvious utility of an accessible medical history for patients and clinicians, routinely collected and detailed health data is also needed to conduct research. A common type of health research is clinical trials, where patients volunteer to participate in studies that generate data designed to evaluate the efficacy of a new medication or procedure. Many studies, however, rely on health information that already exists and that has been collected in a more natural setting. Indeed, data from real-world experience are commonly used in research in the fields of epidemiology, health services research, and public health research.(33) Studies in these areas attempt to identify patterns of occurrences, evaluate the efficacy of health care interventions and services, or assess drug performance, for instance.

Allowing private research institutes to access health information has led to important changes in health policy and the overall practice of medicine. For example, information-based studies have demonstrated that having fewer registered nurses in acute care hospitals leads to a longer hospital stay and a higher likelihood of complications such as urinary tract infections, among others.(34) Studies have also led to significant discoveries and the development of new therapies that can provide a sense of hope for people with rare or chronic conditions.(35) To cite yet another example, research using medical records has established that preventive screenings, such as mammograms, can substantially lower the chances of mortality at reasonable costs.(36)

Clearly, health-related research provides valuable insight for policy-makers and medical professionals alike. Poor data collection and impediments to researchers accessing health information act as a drag on innovation and also prevent policy-makers from detecting possible gaps in the health care system.

In December 2021, the government of Quebec introduced Bill 19, a mammoth piece of proposed legislation that aims to change how health information is managed. Its introduction signals the government’s intention to modernize the health system through the adoption of more efficient practices for sharing health data, starting with an explicit definition of health information.(37)

Importantly, Bill 19 outlines special rules for researchers in the use of health information, and overrides existing obligations under privacy legislation.(38) It aims to stimulate health research by simplifying the process of accessing data for researchers.(39) It calls for a consolidation of health data in a central repository, or access centre, which could then be shared more easily with researchers associated with either public or private organizations in need of anonymized(40) health data.(41) A single request for access to data would be needed to obtain the desired information, greatly simplifying the process. Today, researchers seeking to access health information to conduct research must deposit requests for access to a multitude of organizations.(42)

Important aspects of the reform, however, remain unclear, such as the identity of the body that will act as the access centre for research, as well as the deadline applicable to the processing of requests for access.(43) To help close these gaps, Quebec should learn from other Canadian jurisdictions that have made advances in this regard.

Ontario currently has an interesting model when it comes to sharing health data for research purposes. ICES, formerly the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, is an independent non-profit research institute that secures and analyzes Ontarians’ health information and provides access to health-related data for research purposes to affiliated scientists and trainees, and also to third-party researchers.(44) Founded in 1992, ICES is a leading centre of health services research in Canada.(45) The institute collaborates with data custodians, government, policy-makers, and health system stakeholders to analyze anonymous administrative health data,(46) including visits to doctors’ offices and emergency departments, hospitalizations, and prescription drug use, in addition to home care and long-term care.(47) With this data, multiple aspects of health care in Ontario can be studied, from specific health conditions or medical procedures to metrics of health system performance and patient outcomes.(48)

Data is consolidated in a single repository consisting of around 90 datasets that are linked anonymously, and ICES serves as the steward.(49) As a “Prescribed Entity” under Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act, ICES does not need to obtain patient consent to collect personal health information; however, there is a strict regulatory framework in place that governs its privacy and security policies.(50)

The Time Is Right for Quebec to Act

In addition to the logistical and financial hurdles to the development and adoption of an efficient health data collection system, there is also the matter of social acceptability. Indeed, fears of inadequate privacy protection, and more specifically of information being identifiable and traceable back to the patient, was once an important deterrent to patients consenting to share their health data with research institutions.(51) Yet the type of information sought by researchers is not identifiable data, but rather anonymized data—that is, datasets that have been stripped of any indicators that could lead back to a specific individual. Thankfully, popular opinion in Quebec has shifted on this question, and now nearly 80% of the population would accept that researchers have access to their health data, as long as the information provided does not allow them to be identified(52) (see Figure 2).

The time is therefore right for the Quebec government to catch up on this important issue. Quebec’s health information resources are and have been deficient for some time, lagging what other jurisdictions in Canada have managed to accomplish. The collection, storage, and accessibility of health data need to be reformed, using the systems in place in Alberta and Ontario as guides.

Specifically, Quebec should take the following steps:

- First, health data must be systematically, carefully, and accurately collected.

- Next, the cataloging and storing of handwritten information must become a thing of the past.

- Third, the electronic systems used to gather health information must communicate.

- Finally, the safe and secure sharing of anonymized health data must be streamlined for research purposes.

Ideally, any data necessary for a research project would be obtained via a request to a single entity, much like in Ontario with ICES, though the body responsible for gathering and distributing the health data need not be government-run. Quebec could instead form partnerships with some of the existing organizations in the province that have developed an expertise in the field of data organization.

Quebec needs to bring its health data system into the 21st century, both to maximize patient health today and to encourage innovation for even better care tomorrow.

References

- Pierre-Alexandre Bolduc, “Deux ans de pandémie : des médecins demandent de ‘sortir de l’ère du fax’,” Radio-Canada, March 8, 2022.

- Linda Gyulai, “Fax machine is a vital weapon in Montreal contract tracers’ war against COVID-19,” Montreal Gazette, May 5, 2020.

- The Commonwealth Fund, Electronic Health Records Rollout Begins in Quebec, 2010.

- Claude Gaudet, “Les tours de Babel informatiques,” La Presse, February 7, 2021.

- Jean-Nicolas Blanchet, “Dossier Santé Québec : 450 M$ de plus qu’annoncé,” Le Journal de Montréal, January 13, 2016; Nicholas Lachance, “Nouveau projet monstre après 2G$ et 20 ans d’échecs,” TVA Nouvelles, February 1st, 2021.

- Nicholas Lachance, ibid.; The Commonwealth Fund, op. cit., endnote 3.

- Patrick Bellerose, “Partage des données en santé : Québec veut arriver au 21e siècle,” Le Journal de Québec, December 3, 2021; Government of Quebec, Health, Your health information, Québec Health Record, Available information, consulted March 31, 2022.

- Timothy A.D. Graham et al., “Emergency Physician Use of the Alberta Netcare Portal, a Province-Wide Interoperable Electronic Health Record: Multi-Method Observational Study,” JMIR Medical Informatics, Vol. 6, No. 3, 2018, p. 2.

- Pierre-Alexandre Bolduc, op. cit., endnote 1.

- Government of Quebec, Le Dossier santé numérique et son écosystème – Résultats et recommandations du comité de travail multidisciplinaire du Dossier santé numérique, Department of Health and Social Services, October 18, 2019, p. 18,

- Idem.

- Online MSW Programs, Supporting Survivors of Trauma: How to Avoid Re-Traumatization, consulted March 24, 2022.

- William R. Hersh et al., “Outcomes from Health Information Exchange: Systematic Review and Future Research Needs,” JMIR Medical Informatics, Vol. 3, No. 4, 2015, p. 5.

- Canadian Healthcare Technology, “Quebec aims to ease access to health data,” December 22, 2021; Daniel J. Caron, L’utilisation des systèmes informationnels comme levier à l’amélioration de la performance dans les trajectoires usagers, Chaire de recherche en exploitation des ressources informationnelles, May 2021, p. 17.

- Pierre-Alexandre Bolduc, op. cit., endnote 1.

- Patrick Bellerose, op. cit., endnote 7.

- Government of Quebec, op. cit., endnote 7.

- Government of Quebec, “Dossier santé Québec, Aide-mémoire introduction DSQ,” p. 3, February 2022.

- Kathryn Mercer et al., “Physician and Pharmacist Medication Decision-Making in the Time of Electronic Health Records: Mixed Methods Study,” JMIR Human Factors, Vol. 5, No. 3, 2018, p. 2.

- Daniel J. Caron, op. cit., endnote 14, p. 7; Katia Gagnon and Ariane Lacoursière, “Les six travaux de Christian Dubé,” La Presse, March 20, 2022.

- Government of Quebec, Projet de loi no 19, Loi sur les renseignements de santé et de services sociaux et modifiant diverses dispositions législatives, National Assembly of Quebec, 2021, p. 4.

- Christian Nøhr et al., “Nationwide citizen access to their health data: analysing and comparing experiences in Denmark, Estonia and Australia,” BMC Health Services Research, 2017, p. 3; Roosa Tikkanen et al., 2020 International Profiles of Health Care Systems, The Commonwealth Fund, December 2020, p. 67.

- Timothy AD Graham et al., op. cit., endnote 8, p. 2.

- Government of Alberta, Health, Alberta Netcare, Information for Albertans, Information Included in Alberta Netcare, consulted March 24, 2022.

- Government of Alberta, Health, Alberta Netcare, Information for Albertans, What is Alberta Netcare? consulted March 24, 2022.

- Idem.

- Timothy AD Graham et al., op. cit., endnote 8, p. 9.

- Government of Alberta, Health, Alberta Netcare, For Health Professionals, consulted March 24, 2022; Alberta Health and Alberta Health Services, An Overview of Alberta’s Electronic Health Record Information System, April 2015, p. 9.

- Government of Alberta, ibid.

- Idem.

- In six provinces. Sukirtha Tharmalingam, Simon Hagens, and Jennifer Zelme, “The value of connected health information: perceptions of electronic health record users in Canada,” BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 2016, pp. 6-7.

- Alberta Health and Alberta Health Services, op. cit., endnote 28, p. 7.

- Lawrence Gostin, Laura Levit, and Sharyl Nass, Beyond the HIPAA Privacy Rule: Enhancing Privacy, Improving Health Through Research, 2009, pp. 19-20.

- Jack Needleman et al., “Nurse-staffing levels and the quality of care in hospitals,” New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 346, No. 22, p. 1.

- Lawrence Gostin, Laura Levit, and Sharyl Nass, op. cit., endnote 33, p. 21.

- Jeanne Mandeblatt et al., “The cost-effectiveness of screening mammography beyond age 65 years: A systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force,” Annals of Internal Medicine, Vol. 139, No. 10, 2003, p. 1.

- Fasken, Knowledge, A Quebec law regulating personal information in the health sector, Privacy and Cybersecurity, consulted March 31, 2022.

- Idem.

- Borden Ladner Gervais, Dépôt du projet de loi n° 19 : vers un nouveau cadre juridique en matière de protection des renseignements de santé au Québec, Lexology, December 10, 2021.

- Anonymized data is a set of information that does not contain identifying information. Further details are provided below.

- Borden Ladner Gervais, op. cit., endnote 39.

- Quebec Department of Health and Social Services, Professionnels, Éthique, Éthique de la recherche, Recherche multicentrique, consulted March 31, 2022.

- Borden Ladner Gervais, op. cit., endnote 39.

- ICES, About ICES, consulted March 30, 2022; Michael Schull et al., “ICES: Data, Discovery, Better Health,” International Journal of Population Data Science, Vol. 4, No. 2, 2020, pp. 1 and 4.

- Michael Schull et al., ibid., p. 1; ICES, About ICES, Mission, Vision and Values, consulted March 25, 2022.

- Administrative health data are routinely collected to administer health services under Ontario’s public health care plan. ICES, op. cit., endnote 44, consulted March 30, 2022.

- ICES, “The value of Ontario’s electronic health data infrastructure, A brief report from the perspective of the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences,” October 2016, p. 2.

- ICES, Data & Privacy, ICES Data, consulted March 30, 2022.

- ICES, op. cit., endnote 47, p. 10.

- Michael Schull et al., op. cit., endnote 45, p. 2.

- Marie-Claude Malboeuf, “Le partage des données médicales des Québécois sauverait des vies,” La Presse, April 26, 2018.

- Marie-Claude Malboeuf, “Les Québécois prêts à partager leurs données de santé,” La Presse, December 5, 2021.