Greater Flexibility in Hiring and Firing Teachers Improves Quality of Education

Economic Note showing that students perform better when schools are able to organize their activities as they see fit, including making their own staffing decisions

Greater flexibility in the hiring and firing of teachers would substantially improve the quality of education in Quebec, notes this MEI study. Out of 111,000 Quebec teachers, four were fired for incompetence over the past five years.

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| Interview (in French) with Vincent Geloso (Alexandre Dubé, QUB Radio, August 24, 2023) | Interview with Vincent Geloso (CTV News Montreal at Noon, CFCF-TV, September 6, 2023) |

This Economic Note was prepared by Emmanuelle B. Faubert, Economist at the MEI, and Vincent Geloso, Senior Economist at the MEI. The MEI’s Education Series aims to explore the extent to which greater institutional autonomy and freedom of choice for students and parents lead to improvements in the quality of educational services.

There is a large empirical literature in economics connecting ease of hiring and firing to greater productivity, higher income levels, and higher quality of services.(1) The main reason for this empirical finding is that firms can get rid of workers who prove to be ill-suited for their needs and more easily try again with new workers who might be a better fit.

Few dispute the importance of this mechanism. Yet there is a steadfast refusal to rely on this principle for one particular group of workers in Quebec: teachers. Over the past decade, the provincial government has considered numerous schemes to try to improve the quality of teaching in Quebec’s primary and secondary schools. Widely discussed were smaller class sizes, teacher evaluations, a professional order of teachers, stricter qualification rules, and performance bonuses. But rarely was the possibility of decentralizing school administration and making it easier to hire and fire teachers even mentioned.

The Importance of Flexibility in Hiring and Firing

Everyone agrees good teachers are important. However, given the range of other relevant variables such as class size, educational resources, and curriculum constraints, exactly how important is less obvious. For instance, one could argue that a teacher with a class of fifty students is unlikely to deliver a satisfying performance regardless of skill level.

A recurrent finding from empirical studies, though, is that class size and spending per pupil have relatively small effects on student performance.(2) The competence of teachers outweighs these variables by large margins.(3) One frequently-cited study(4) finds that the effect on schooling outcomes of improving teacher competence by one standard deviation is far greater than cutting class size by ten students (a 33% reduction in the case of Quebec high schools).(5) It is also a stronger determinant of later-life student outcomes such as adult income and higher education levels.(6)

An underperforming teacher might be endured by a school administrator who prefers to avoid the lengthy process of securing a dismissal.

However, the competence of teachers is not well-measured by formal qualifications such as degrees,(7) nor can most of what constitutes competence—things like motivation, creativity, adaptability—be easily measured at hiring time. Moreover, there tends to be some statistical “noise” in evaluations during the first few years of teachers’ careers as they find their footing. As such, a teacher who stumbles in the first months on the job is hard to distinguish from an incompetent one. It is only after a few years of experience that competence can be assessed more reliably.(8)

These difficulties suggest that it would be best to hire teachers and observe them for a number of years, and then retain the best performers.(9) That is insufficient to ensure competence, however, as retained teachers offered job security might see little incentive to continue to improve or adapt.(10) To ensure teacher competence, then, easier hiring and firing must be allowed.

The Difficulty of Hiring and Firing teachers in Quebec

Several hurdles exist to the hiring and firing of teachers in Quebec. There are numerous restrictions on hiring people with highly specialized degrees who want to become teachers, for instance, while qualified immigrants (except for those from France) also face restrictions regarding the recognition of their skills.(11) This is despite recurrent complaints of a shortage of teachers in the province. Moreover, hiring decisions are not made at the school level, but rather at the more centralized school board level, far from where the repercussions of those decisions are felt.(12)

Even more problematic, though, are the numerous hurdles that exist to getting rid of incompetent or otherwise unsuitable teachers. First and foremost, local collective agreements signed between teachers’ unions and the provincial government specify highly elaborate and complicated procedures for assessing competence, granting job security, and seeking dismissal.(13)

The local agreements specify procedures for evaluating performance before granting job security. However, once this is done, there is little further formal evaluation.(14) Teachers are not evaluated according to improvements in student outcomes or with reference to the difficulty of the content and groups they teach.

From 2018 to 2023, around 0.0036% of teachers were fired for incompetence. This number is implausibly low.

There is a process of “pedagogical supervision” for problematic teachers. However, it is largely ineffectual. First, it offers highly subjective guidelines with no penalties for the teacher.(15) Second, the process of securing a dismissal is long and difficult. The proposal to dismiss must be formally documented. This can then be contested by the teacher’s union, and deliberation ensues. Each step of the process requires further documentation, and cases for dismissals generally drag on for months, often years.

As such, an underperforming teacher who is not grossly incompetent (but who is incompetent enough to seriously undermine educational outcomes) might be endured by a school administrator who prefers to avoid the lengthy process of securing a dismissal. To do so, the bureaucratic grids of analysis produced by the Department of Education may be liberally interpreted. In other instances, an underperforming teacher might simply be shifted into another function.(16)

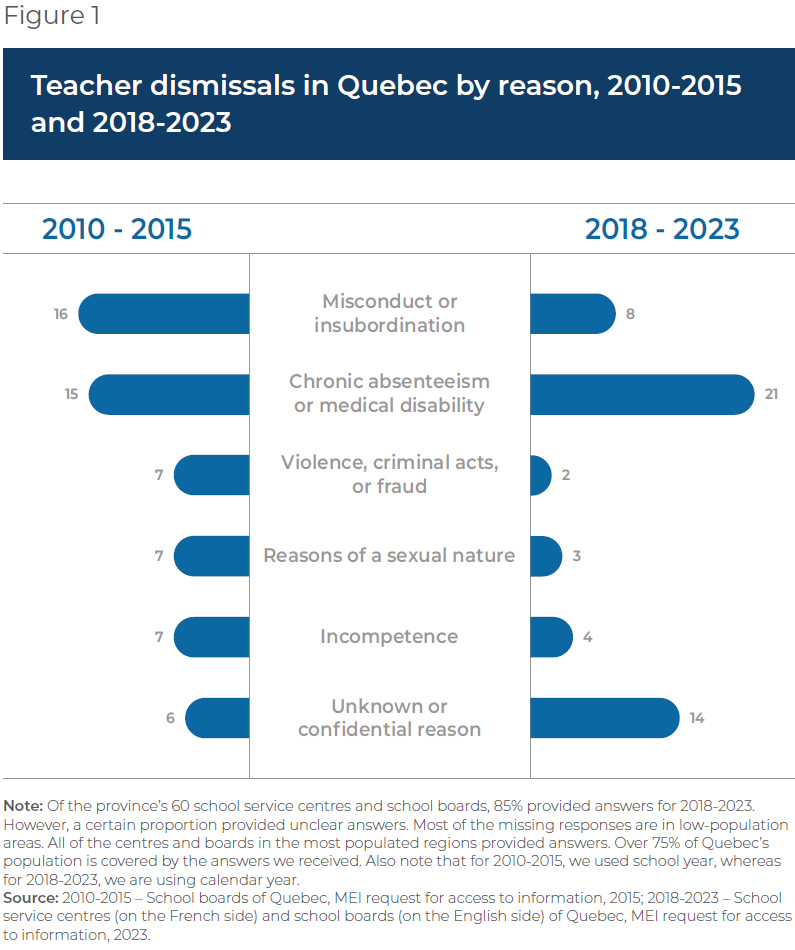

These difficulties are evident when we look at the data. In 2016, the MEI sent requests for access to information on firings to all the school boards in Quebec, the first such province-wide request.(17) The vast majority of the school boards provided answers regarding firings between 2010 and 2015. Over the entire period, just 58 teachers had been fired, and only 7 of these dismissals were for incompetence. As a proportion of all teachers, this means that 0.007% of teachers were fired for incompetence, which suggests that fewer than one in 10,000 teachers is incompetent. This is of course highly implausible, especially given that Quebec has one of the lowest rates of high school completion in Canada.(18)

We have now repeated this exercise for the period from 2018 to 2023 and found that those earlier results were not an anomaly. As can be seen in Figure 1, the total number of dismissals actually fell to 52 over this latter period, while the reported number of teachers fired for incompetence fell to 4. Given that there are more than 111,000 teachers in the province (with more than 60,000 being permanent), this means that around 0.0036% of teachers were fired for incompetence.(19) This number is again implausibly low.

Decentralization and Competition

Removing bureaucratic hurdles to hiring and firing is the best way to improve teaching performance. The only question is how to proceed. Hiring and firing based on province-wide standards is not the best approach. As there are significant differences in the populations being served by different schools, what counts as competence is to some extent relative to the social context.(20) A certain highly competent teacher might be ill-suited to teach in one area, but would excel in another.(21) This suggests the need for a more decentralized system whereby schools retain more powers to organize their activities as they see fit, including making their own staffing decisions.

Students perform better when schools have more autonomy in terms of personnel and day-to-day administration.

The outcomes from decentralization are generally positive, as cross-country analyses show that students perform better when schools have more autonomy in terms of personnel and day-to-day administration.(22) One notable study concerns Norway, where school districts can choose whether to decentralize hiring decisions. Districts that decentralized hiring and firing decisions were found to have exhibited higher levels of efficiency and better student performance.(23) Moreover, since this Scandinavian country has a highly centralized education system in general, its decentralization efforts provide evidence that should be applicable to Quebec’s quite centralized system.

The advantages of school decentralization could be increased even further if school funding were tied to parental choice. This is because parental decisions to send their children to one particular school rather than another provide feedback to school administrators about whether they are doing a good job.(24) This in turn provides additional incentive for them to make the best staffing decisions they can.

The provincial government should do what it can to support high-quality education for Quebec students. Research shows that this means allowing school administrators to make their own hiring and firing decisions, and giving them every reason to choose wisely.

References

- Horst Feldmann, “The effects of hiring and firing regulation on unemployment and employment: evidence based on survey data,” Applied Economics, Vol. 41, No. 19, 2009, pp. 2389-2401; Giuseppe Bertola, “Job security, employment and wages,” European Economic Review, Vol. 34, No. 4, 1990, pp. 851-879; Paolo Sestito and Eliana Viviano, “Firing costs and firm hiring: evidence from an Italian reform,” Economic Policy, Vol. 33, No. 93, January 2018, pp. 101-130; Hernan J. Moscoso Boedo and Toshihiko Mukoyama, “Evaluating the effects of entry regulations and firing costs on international income differences,” Journal of Economic Growth, Vol 17, No. 2, June 2012, pp. 143-170.

- Eric A. Hanushek, “The failure of input‐based schooling policies,” Economic Journal, Vol. 113, No. 485, February 2003, pp. F64-F98; Desire Kedagni et al., “Does class size matter? How, and at what cost?” European Economic Review, Vol. 133, April 2021.

- Steven G. Rivkin, Eric A. Hanushek and John F. Kain, ”Teachers, schools, and academic achievement,” Econometrica, Vol. 73, No. 2, March 2005, pp. 417-458.

- Ibid., p. 417.

- Derek J. Allison, Secondary Class Sizes and Student Performance in Canada, Fraser Institute, September 2019, p. 9.

- Dan Goldhaber, Roddy Theobald, and Danielle Fumia, “The role of teachers and schools in explaining STEM outcome gaps,” Social Science Research, Vol. 105, July 2022; Raj Chetty, John N. Friedman, and Jonah E. Rockoff, “Measuring the impacts of teachers II: Teacher value-added and student outcomes in adulthood,” American Economic Review, Vol. 104, No. 9, September 2014, pp. 2633-2679.

- Jonah E. Rockoff, “The impact of individual teachers on student achievement: Evidence from panel data,” American Economic Review, Vol. 94, No. 2, May 2004, pp. 247-252.

- Douglas O. Staiger and Jonah E. Rockoff, “Searching for effective teachers with imperfect information,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 24, No. 3, 2010, pp. 97-118.

- Ibid., p. 97.

- Randall Reback, Jonah Rockoff, and Heather L. Schwartz., “Under pressure: Job security, resource allocation, and productivity in schools under No Child Left Behind,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, Vol. 6. No. 3, August 2014, pp. 207-241; Matthew A. Kraft et al., “Teacher accountability reforms and the supply and quality of new teachers,” Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 188, August 2020; Nathan Barrett, Katharine O. Strunk, and Jane Lincove, “When tenure ends: the short-run effects of the elimination of Louisiana’s teacher employment protections on teacher exit and retirement,” Education Economics, Vol. 29, No. 6, November 2021, pp. 559-579.

- Marie-Eve Morasse, “Profs sans brevet cherchent voie rapide,” La Presse, December 14, 2022.; Government of Quebec, Diplômes et documents de titularisation reconnus pour les enseignantes et enseignants provenant de France, consulted July 12, 2023.

- Government of Quebec, Entente intervenue entre d’une part, le comité patronal de négociation pour les Centres de services scolaires francophones (CPNCF) et d’autre part, la Centrale des Syndicats du Québec pour le compte des syndicats d’enseignantes et enseignants qu’elle représente, 2021, Article 5-1.02.

- Ibid., Article 5-7.00

- Nathan Béchard and Marthe Hurteau, “Évaluation des enseignants permanents du secondaire au Québec : quelle démarche préconiser selon des enseignants et des directeurs d’école?” Formation et profession, Vol 28, No. 3, 2020, pp. 18-35.

- Ibid.; Quebec Department of Education, La formation à l’enseignement : les orientations, les compétences professionnelles, 2001.

- Daniel Leblanc, “Le congédiement d’un enseignant est extrêmement rare,” Le Droit, June 12, 2023.

- Youri Chassin, “Enhance the Standing of the Teaching Profession by Firing Incompetent Teachers,” Economic Note, MEI, January 2016.

- Nikola Elez and Klarka Zeman, “High School Graduation Rates in Canada, 2016/2017 to 2019/2020,” Education Indicators in Canada: Fact Sheet, Statistics Canada, October 20, 2022.

- Quebec Auditor General, Rapport du Vérificateur général du Québec à l’Assemblée nationale pour l’année 2022-2023, “Chapitre 3 : Personnel enseignant : recrutement, rétention et qualité de l’enseignement,” May 2023, p. 16.

- Huriya Jabbar, “Recruiting ‘talent’: School choice and teacher hiring in New Orleans,” Educational Administration Quarterly, Vol. 54, No. 1, July 2017, pp. 115-151; John Bishop and Ludger Wossmann, “Institutional effects in a simple model of educational production,” Education Economics, Vol. 12, No. 1, 2004, pp. 17-38.

- This is one reason why the empirical literature tends to find that variables like a teacher’s formal education and experience have little predictive power when it comes to schooling outcomes.

- Ludger Wößmann, “Schooling resources, educational institutions and student performance: the international evidence,” Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 65, No. 2, May 2003, pp. 117-170.

- Linn Renée Naper, “Teacher hiring practices and educational efficiency,” Economics of Education Review, Vol. 29, No. 4, August 2010, pp. 658-668.

- Vincent Geloso, “Improving Schooling Outcomes: It’s about Choice, Not Spending More,” Economic Note, MEI, August 2022.