How to Successfully Reduce the Regulatory Burden

In its last Fall Economic Statement, the federal government included a chapter on regulation. It intends to review and remove outdated or duplicative regulatory requirements, keep an eye on our regulatory burden’s effect on our competitiveness, and innovate when it comes to rule-making. While this is a welcome admission that the Canadian regulatory burden is weighing down our competitiveness, with the United States as an easy alternative destination for investment, it still leaves open the question of how exactly to proceed with effectively reducing the regulatory burden.

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| How to reduce the regulatory burden (The Hill Times, February 7, 2019)

Comment réduire le fardeau réglementaire (Le Droit, February 13, 2019) |

This Economic Note was prepared by Mathieu Bédard, Economist at the MEI, and Kevin Falcon, Executive Vice President of Anthem Capital, former Minister of State for Deregulation in British Columbia, and Senior Fellow at the MEI. The MEI’s Regulation Series aims to examine the often unintended consequences for individuals and businesses of various laws and rules, in contrast with their stated goals.

In its last Fall Economic Statement, the federal government included a chapter on regulation. It intends to review and remove outdated or duplicative regulatory requirements, keep an eye on our regulatory burden’s effect on our competitiveness, and innovate when it comes to rule-making. While this is a welcome admission that the Canadian regulatory burden is weighing down our competitiveness, with the United States as an easy alternative destination for investment, it still leaves open the question of how exactly to proceed with effectively reducing the regulatory burden.(1)

The Problem with Regulation

A regulation is a “law” that is created under the authority of a statute or act.(2) It supports the requirements of such legislation, and provides instructions on how to implement, interpret, and enforce it. By its very nature, regulation prevents companies and individuals from making choices that they would have made in the absence of such regulation.

Most regulation serves a seemingly reasonable purpose. Yet, even when it does serve a purpose, it has a cost. Nearly all regulation is a barrier to entry that makes it harder to launch a business—yet entrepreneurs launching businesses is a big part of what makes for a more competitive economy, lowering the price of goods and services and raising standards of living for all. Because regulation protects the market shares of firms that are already established, which are often not the most productive (and are even sometimes unproductive), it also affects productivity throughout the economy and, ultimately, keeps wages from rising.

While lost opportunities from barriers to entry into business are a very important cost, and lost opportunities for investment are another type, others include regulatory agency spending, regulatory agency personnel compensation, business compliance costs, and the costs of demonstrating to officials that businesses are compliant. The last two are borne by private enterprise. This means they are invisible in a government budget, yet they have a very substantial impact on job creation, wage growth, and the progress of living standards.

Canada has plenty of regulation that stifles entrepreneurship and drags our economy down. One way to measure this regulatory burden is to count the total number of requirements that impose an administrative burden on business. These include reporting or submitting information to the regulatory body, seeking authorizations such as permits, and audits, inspections, or meetings that businesses might have to hold because of regulation—whether these are directly spelled out in regulations properly speaking, or in “regulation” made by a Minister or any other authority with regulatory powers.(3)

Federal regulations administered by Health Canada account for 15,875 of these requirements. Federal regulations administered by the Canadian Revenue Agency add another 1,808. At Finance Canada, the count is 4,519. In total, according to the Administrative Burden Baseline that government agencies are required to publish yearly, there were 136,121 such requirements imposed on businesses by the federal government alone.(4)

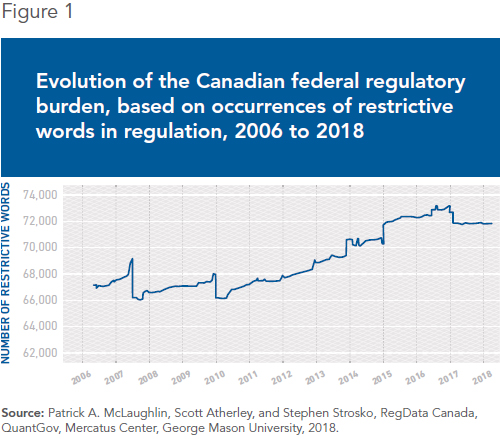

Another way to measure the regulatory burden is to look at the regulations on the books, and count how many restrictive words they include. Figure 1 represents the evolution of how many times the words “shall,” “must,” “may not,” “required,” and “prohibited” are found in the texts of federal regulations, orders, bylaws, and rules. There are close to 72,000 of these restrictive words in Canada’s federal regulations, and their number has gone up over the past twelve years.

Provinces also impose a significant regulatory burden. While each province’s methodology differs, and they are thus not directly comparable, it is nonetheless interesting to learn that recent reports by different provincial governments have found 170,140 requirements in British Columbia,(5) some 230,000 in Saskatchewan,(6) 386,251 in Ontario,(7) and a whopping 924,180 requirements in Manitoba.(8)

A textual analysis, similar to the one carried out for the federal government, however, shows that the regulatory burden for Ontario is the steepest, with 77,000 restrictive words, Quebec being a close second at 59,000. Alberta (33,000), Nova Scotia (32,000), and Saskatchewan (28,000) round out the top five, with the count in the other provinces ranging from 22,000 in Manitoba to 14,000 in Prince Edward Island.(9)

The effect of this regulatory burden, according to recent research from Finance Canada staff published in a peer-reviewed journal, is to significantly hamper foreign direct investment. If our regulatory burden were the same as that of the United States, per capita GDP would be 2% higher after 5 years, and 5.3% higher after 20 years.(10) This is more than enough economic growth to prevent a mild recession, should it come to that.

Ottawa’s Attempts to Reduce the Burden

A certain number of federal government initiatives have tried to limit the growth of the regulatory burden, with only the mitigated success displayed in Figure 1.

One of the initiatives the federal government has put in place is a way to keep track of the cost of regulation. The number of requirements imposed on businesses has been tracked by each federal agency since 2014, and when a new regulation is being considered, officials are required to conduct a regulatory impact analysis, the basis and depth of which is determined by the regulation’s associated costs.

By no means does this analysis provide a complete account. What it does is count the burden imposed on business by regulation, but not the burden imposed by legislation and policies. Before new regulation is approved, it requires regulators to estimate a cost for this “red tape,” both the cost associated with the amount of paperwork required from private business to demonstrate to government officials that they are compliant, and some estimate of the spending that will be associated with the new regulation. These might include buying new material, training employees, etc.(11) The level of precision of these estimates is based on the anticipated costs; a regulation with an annual impact of less than $1 million only requires a qualitative analysis of its costs and benefits, while a regulation with an anticipated annual impact greater than $1 million must have its costs and benefits quantified and “monetized.”(12)

These costs are then used in applying the federal government’s One-for-One Rule, which states that regulators are required to offset new costs within two years of receiving final approval of regulatory changes that impose a new administrative burden on business.(13) Not measured are their indirect impact on government budgets, on competition, on trade, on innovation, on market openness, on specific regional areas, on non-profit organizations, on the public sector, or on poverty. In theory, the regulatory burden defined in this narrow way, at least, should remain relatively stable in Canada thanks to the One-for-One Rule—as long as you turn a blind eye to new regulations that are exempted from these requirements each year.

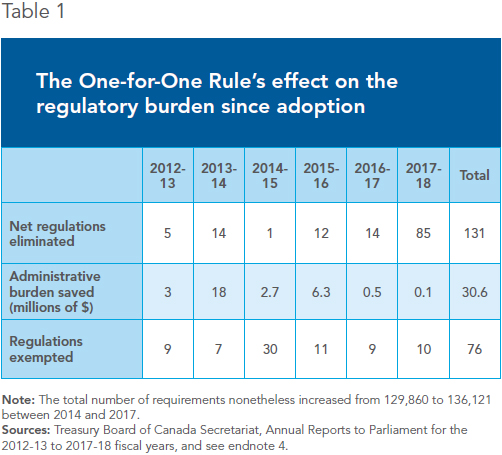

From 2012-2013 to 2017-2018, there were 131 individual regulations eliminated by the federal government through its One-for-One Rule (see Table 1). The net effect on the administrative burden was to decrease it by $30.6 million. There were, however, 76 new regulations added during this time which were exempted from One-for-One Rule considerations, and whose costs were not calculated by the government. Such exemptions have to do with tax administration, regulations where government has no discretion (because of international treaties for example), or for reasons of emergency that would threaten the economy, health, or safety. While it is reasonable that some regulations should be exempted from such administrative burden accounting and constraints (as long as emergency reasons are not used merely as an excuse to circumvent the rule), they nevertheless do add to the regulatory burden.

Furthermore, because it is impossible to predict all of the ramifications of new regulations and their impact on industry, even for businesses themselves, these exercises are bound to underestimate compliance costs. The reason this impact is so hard to predict is that when the rules change, the behaviours of the people facing the new rules also change. A new restrictive regulation may lead an entrepreneur to reduce business investment, to hire fewer additional staff members, to postpone plans to expand into new markets, and so on.

Moreover, these estimates are not subject to much public scrutiny; they are currently only prospective, largely based on comments received in public consultations, and not reviewed once the rule is implemented; and they are conducted by the agencies themselves, which have goals of their own that are often in conflict with the goal of reducing the regulatory burden.(14)

Clearly, this approach, while based on international standards promoted by organizations like the OECD, has not reined in the growth of the regulatory burden, much less reduced that burden, since coming into effect in 2012.

Recent initiatives, outlined in the 2018 Fall Economic Statement, promise a yearly review, intended to further reduce the regulatory burden.(15) While it is early, and details about this policy change are scarce, it does seem like it will still be guided by the same method that has produced very mixed results so far. Moreover, recent legislation, some of which already figures in the Government’s Forward Regulatory Plan, undermines, and sometimes openly contradicts, the commitment to streamlining the regulatory burden.(16)

Inspiration from Canadian Successes

While it is perfectly reasonable to want reforms to be grounded in an algorithm, and some form of cost-benefit analysis such as the method used by the federal government, it would be helpful to look at a past Canadian success at reducing the regulatory burden. A great example is the reduction of the regulatory burden in British Columbia after 2001, which one of us took part in. The British Columbia Liberal Party had been elected on a platform promising a 33% reduction in the regulatory burden. After three years, it had exceeded its target and eliminated 37% of the regulatory burden.(17) How the province did it has been extensively documented and commented on.(18) There were, essentially, three key elements:

1. A method of account for the regulatory burden

2. A clear regulatory burden reduction target

3. Political leadership buying into this goal

The B.C. government developed the initial administrative burden method of account that inspired (and was improved upon by) the federal government.

But perhaps more importantly, along with the clear reduction target, there was political will to shrink the regulatory burden. Premier Gordon Campbell and one of us, Kevin Falcon, then Cabinet minister responsible for deregulation, made sure all Cabinet ministers were held accountable, through a process that could be described as Cabinet peer pressure.(19)

Such Cabinet peer pressure was also employed with great success at the federal level by the Jean Chrétien government, with Paul Martin as its Minister of Finance, to reduce the Canadian deficit through its Program Review, launched in 1994. While this episode concerns public finances rather than the regulatory burden, this political leadership process likewise involved a strong political commitment and personal involvement from the top executive of the government and one of his key ministers, holding other ministers and their departments accountable, and regular discussion and updates of these issues in Cabinet meetings.(20) It is widely recognized at the international level as one of the great Canadian fiscal success stories.

What Is Missing from the Federal Approach?

The federal government already has a method of account for the regulatory burden that is, despite its limitations, in line with international best practices recommended by organizations like the OECD.(21) While this system and methodology are currently used prior to the adoption of new regulations, there are no insurmountable challenges to adapting them into a tool for eliminating cumbersome regulations already in place.

What is missing, though, is a firm government commitment to a clear reduction target, and the political leadership to make reducing the regulatory burden a key objective and hold all of the Cabinet accountable. These are indispensable elements to any successful effort to improve the policy landscape.

References

1. The Canadian regulatory burden is substantially higher than the American one for all years where both countries are evaluated simultaneously (1998, 2003, and 2008). Isabell Koske et al., The 2013 update of the OECD’s database on product market regulation: Policy insights for OECD and non-OECD countries, March 2015, p. 29.

2. Government of Canada, Privy Council Office, Guide to Making Federal Acts and Regulations, Part 3 – Making Regulations.

3. In other words, both Governor in Council regulation and non-Governor in Council regulation are included. Government of Canada, Counting Administrative Burden Regulatory Requirements, Definitions.

4. Government of Canada, Government-wide Administrative Burden Baseline Counts: Update 2017. Note: Despite the website’s name, the figures in-text actually use the 2018 updates, except for a few agencies where the count was not available yet. In those cases, the 2017 count was used.

5. Ministry of Small Business and Red Tape Reduction and Responsible for the Liquor Distribution Branch, 2016/17 Annual Service Plan Report, British Columbia, 2017.

6. Government of Saskatchewan, Annual Regulatory Modernization Progress Report for 2017-18, 2018.

7. Ministry of Economic Development, Job Creation and Trade, “Small business sector: Meeting report,” November 13, 2015.

8. Government of Manitoba Regulatory Accountability Secretariat, Manitoba Regulatory Accountability Report, September 2018.

9. Patrick A. McLaughlin, Scott Atherley, and Stephen Strosko, RegData Canada, QuantGov, Mercatus Center, George Mason University, 2018.

10. Aled ab Iorwerth and Carlos Rosell, “The Gains from More Competitive Regulation Settings in Canada,” International Productivity Monitor, Vol. 34, spring 2018, pp. 3-20.

11. These estimates do not, and should not, include the cost of taxes and permits, however, because these are already accounted for in government budgets. Government of Canada, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, Policy on Limiting Regulatory Burden on Business, The small business lens.

12. Between an annual cost of $1 million and $10 million, the benefits are only quantified and “monetized” if data are readily available. Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, Annual Report to Parliament for the 2017 to 2018 Fiscal Year: Federal Regulatory Management Initiatives, December 2018.

13. Government of Canada, Backgrounder – Legislating the One-for-One Rule, May 22, 2015.

14. Robert W. Hahn and Paul C. Tetlock, “Has Economic Analysis Improved Regulatory Decisions?” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 22, No. 1, 2008, pp. 67-84; Jerry Ellig and Richard Williams, Reforming Regulatory Analysis, Review, and Oversight, Mercatus Center, George Mason University, August 2014.

15. Department of Finance Canada, Investing in Middle Class Jobs: Fall Economic Statement 2018, November 21, 2018, pp. 72-76; Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, Cabinet Directive on Regulation, September 1st, 2018.

16. Such is the case, for example, of Bill C-69, currently being reviewed by the Senate. Government of Canada, Government-Wide Forward Regulatory Plans; Martha Hall Findlay, “Bill C-69 is the antithesis of what the regulatory reform effort hopes to achieve,” The Globe and Mail, December 2, 2018.

17. Laura Jones, Cutting Red Tape in Canada: A Regulatory Reform Model for the United States? Mercatus Center, George Mason University, November 2015, p. 20.

18. Ibid.; Steven Globerman, Strategies for Deregulation: Concepts and Evidence, Fraser Institute, October 23, 2018; Sean Speer, Regulatory Budgeting: Lessons from Canada, R Street Policy Study No. 54, March 2016.

19. Jocelyne Bourgon, The Government of Canada’s Experience Eliminating the Deficit, 1994-1999, The Centre for International Governance Innovation, 2009.

20. Donald J. Savoie, Governing from the Centre: The Concentration of Power in Canadian Politics, University of Toronto Press, 1999, p. 183; Reuters, “Interview with Canada’s former-PM Chretien,” November 21, 2011.

21. Rex Deighton-Smith, Angelo Erbacci, and Céline Kauffmann, Promoting Inclusive Growth through Better Regulation: The Role of Regulatory Impact Assessment, OECD Regulatory Policy Working Papers No. 3, 2016.