What Are the Benefits of Economic Freedom?

A useful and intuitive definition of “economic freedom” is the freedom (absence of coercion) to buy from, or sell to, a willing counterparty. A society based on economic freedom is a free-market society. But is economic freedom economically beneficial? Is it all about money? Is it moral? Aren’t there many exceptions where government intervention is warranted? This Economic Note addresses these questions.

Media release: The fight against poverty depends on economic freedom

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| La liberté économique, à quoi ça sert? (Huffington Post Québec, October 25, 2018)

Why we have it so good (National Post, October 31, 2018) |

This Economic Note was prepared by Pierre Lemieux, an economist affiliated with the Department of Management Sciences of the Université du Québec en Outaouais, and Senior Fellow at the MEI, in collaboration with Alexandre Moreau, Public Policy Analyst at the MEI. This publication is disseminated in Europe thanks to a partnership with the Molinari Economic Institute.

A useful and intuitive definition of “economic freedom” is the freedom (absence of coercion) to buy from, or sell to, a willing counterparty. A society based on economic freedom is a free-market society.(1) But is economic freedom economically beneficial? Is it all about money? Is it moral? Aren’t there many exceptions where government intervention is warranted? This Economic Note addresses these questions.

Freedom Makes Us More Prosperous

The most obvious benefit of economic freedom is that, as a system, it is the most conducive to widespread prosperity, that is, to high or rising income and consumption for the bulk of the population.

History strongly suggests that countries with more economic freedom grow faster—and those with less economic freedom sometimes don’t grow at all. The real GDP per capita of the United Kingdom, the spearhead of the Industrial Revolution, was multiplied by 16 in the three centuries since 1700, according to recent estimates from economic historians. Over the preceding 700 years, it had only doubled. Other Western countries, including Canada and the United States, followed in the U.K.’s footsteps.(2)

Economic growth is a matter of good institutions (including economic freedom), not a matter of natural resources.(3) Hong Kong, a semi-independent territory of the United Kingdom until 1997, provides a good example. The Economic Freedom of the World (EFW) index, compiled by the Fraser Institute since 1970, has generally ranked the tiny, resource-poor country as the economically freest country in the world.(4) This freedom has paid off in terms of economic growth: While Hong Kong’s GDP per capita amounted to 33% of the Canadian level in 1950, it had reached 108% in 1997.(5)

Another telling example of the benefits of economic freedom is provided by the two Koreas, which shared the same culture and were at roughly the same level of development when they separated in 1948. They subsequently followed very different paths: a good measure of economic freedom in the South, and none in the North. GDP per capita in the South is now 20 times higher than in the North.(6)

The recent rise of China does not contradict this theory. Nobel Prize-winning economist Ronald Coase argued that China gradually became (partly) capitalist after the death of Mao Zedong,(7) which explains its high rates of economic growth. (A return to open dirigisme will likely stop this momentum.)(8)

Over the past few decades, the governments of many poor countries have allowed more economic freedom. The result has been a dramatic escape from dire poverty for billions. Between 1981 and 2015, the proportion of the world population living in extreme poverty (on less than $1.90 a day(9)) fell from 42% to 10%.(10)

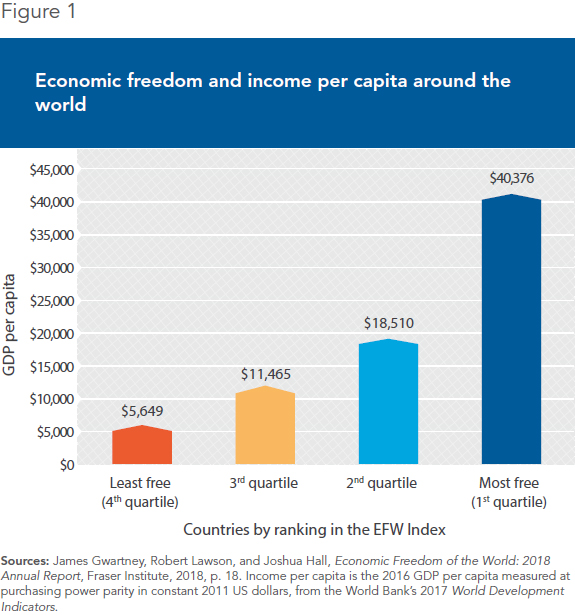

The EFW index combined with World Bank data on economic growth suggest that more economic freedom over the past 25 years is associated with higher incomes today. Figure 1 shows that average GDP per capita increases continuously from the least economically free countries (the bottom quartile of the EFW index) to the freest (the top quartile).

Correlation is not causation, of course, but it helps confirm a theoretical result—in this case, that the quality of social, political, and economic institutions matters for economic growth. These institutions include the rule of law, private property, and economic freedom—which generally go together.(11)

It’s Not Only About Money

There are many benefits to economic growth. It translates into higher absolute levels of income for the poor, even when inequality rises. The level of income of the poorest 10% of individuals is about 8 times higher in the most economically free countries (US$10,660) than in the least free ones (US$1,345). Life expectancy in the most economically free countries (79.4 years) is also 15 years higher than in the least economically free (64.4 years).(12)

More production and income per capita helps individuals pursue the lifestyles they want, each according to their own preferences, more materialistic for some, more spiritual for others. Some individuals may choose to enjoy more leisure and consume less. The point is that high income per capita is indicative of more opportunities for more people.

Moral arguments also support economic freedom. The simplest one is that, to paraphrase philosopher Robert Nozick, economic freedom is the freedom to engage in “capitalist acts between consenting adults.”(13)

Economic freedom and other components of individual liberty generally go hand in hand. Comparing the EFW index with Freedom House’s Freedom in the World index of political freedom (that is, political and civil rights), we observe a close correlation: The less economically free countries are also the ones that enjoy less political freedom.(14)

Economic freedom is not a sufficient condition for individual liberty in general, for we know some authoritarian countries (Singapore, for example(15)) where a large measure of economic freedom exists. However, economic freedom does appear to be a necessary condition of individual liberty: It is difficult to imagine meaningful individual liberty if individuals are told what to buy, what to sell, and where to work.(16) In practice, individual liberty and economic freedom generally go together.

The more government monopolizes both political and economic power, the more it is able, and tempted, to exploit unpopular minorities and to control dissent. Dissent is difficult if the government can prevent dissenters from buying, say, computers or smartphones, or finding gainful employment.(17)

Some Objections to Economic Freedom

Many objections to economic freedom take the form of “Yes, economic freedom is good, but…” There are of course extreme cases when economic freedom cannot be deemed beneficial because large costs are imposed upon third parties who are not or cannot be compensated. For example, hiring a hitman is understandably prohibited.

More generally, exchanges that impose on third parties significant costs that are not compensated by larger benefits—so-called “negative externalities”—do not fall in the domain of economic freedom. Negative externalities include some pollution phenomena that can’t be solved by freely tradable private property rights (although there is a danger of calling “pollution” anything somebody somewhere does not like).(18)

Most objections to economic freedom, however, are unrelated to extreme or genuine externality cases. Instead, they negate the very principle of economic freedom. It is beyond the scope of the present study to review all such objections, but considering some central ones will provide keys to dealing with others.

One common objection to economic freedom is that it increases income inequality. But this is not necessarily true. Many countries (including in South America) are among the least economically free (according to the EFW index) and also the most unequal, as measured by their Gini coefficients.(19) On the contrary, some free countries such as Switzerland (4th rank in economic freedom) and Ireland (5th rank) have relatively low Gini coefficients (32.5 and 33.5 in 2013).(20) Indeed, we would normally expect economic freedom to favour creative destruction and the flattening of class barriers.

In fact, some government restrictions to economic freedom have likely contributed to inequality. Think about anticompetitive privileges (including protectionist barriers and the excessive protection of intellectual property) and subsidies to corporations. Such interventions, often called “crony capitalism,” mainly benefit the rich.(21)

At any rate, the increase in inequality since the 1980s is easy to exaggerate,(22) and furthermore has many legitimate causes. The shock of rapid technological change and the evolution of marital practices (more people marry people with similar levels of income, for example)(23) are two such causes.

Moreover, even if inequality has trended higher, the absolute income levels of the lower income classes have generally increased. And we saw above that the poor are generally much less poor in freer countries.

Finally, inequality has decreased globally, that is, taking into account the economic growth of poor countries. Branko Milanovic, a World Bank economist, suggests that the period from 1988 to 2008 “has witnessed the first decline in inequality between world citizens since the Industrial Revolution.”(24)

Another objection is that economic freedom should be sacrificed to the welfare state. Such a sacrifice is dangerous and ultimately self-defeating. Social programs are less necessary when general prosperity obtains, and often impossible to finance without it. These programs, when they are needed or unavoidable, should aim at helping the poor through general redistribution, not through direct economic interventions (minimum wages, trade union privileges, and other regulations on businesses and consumers) that directly infringe on economic freedom.

Still another major objection is that economic freedom is less valuable if some other places have less of it—if, for example, foreign businesses are “unfairly” assisted or protected by their governments. In an ideal world, of course, all exchange partners (and taxpayers) would enjoy the same level of economic freedom. But there is little we can do to promote foreigners’ economic freedom, except provide a good example of its efficiency and desirability by maintaining it at home. As economist Joan Robinson quipped, protectionist retaliation looks as sensible as “dump[ing] rocks into our harbors because other nations have rocky coasts.”(25)

Moreover, determining who is more subsidized or hampered is generally an impossible task, so numerous are government interventions and so intricate their consequences.

Finally, except in an ideal (and unrealistic) socialist society where the state would equalize all conditions of life, there is no such thing as a “level playing field.” Competing means surmounting all the handicaps imposed by competitors or circumstances, natural or man-made. Protecting equal freedom for all at home is desirable, and is what can be realistically achieved.(26)

The Danger of Expediency

Perhaps the most potent argument for economic freedom is what happens when economic freedom is compromised. The consequences are obvious in extreme cases—say, Soviet Russia, Venezuela, or North Korea—but they are also detrimental, to a lesser extent, in freer societies. It is a matter of degree, but we should not conclude that a government can without danger pile one exception on top of another for reasons of expediency.

Expediency—choosing each new government intervention on its own merits, without looking at the broad systemic danger—can lead to a slide into a socialist (or fascist) society as the government will be continuously called upon to correct with new interventions the negative consequences of its previous interventions, as Friedrich A. Hayek, another Nobel prize-winning economist, pointed out.(27) There is no natural or automatic stopping point.

While some benefits of restricting economic freedom can often be identified in a specific case, the costs in terms of missed opportunities for future entrepreneurship and innovation are invisible. “Since the value of freedom rests on the opportunities it provides for unforeseen and unpredictable actions,” wrote Hayek, “we will rarely know what we lose through a particular restriction of freedom.”(28)

To summarize, a social and political system based on economic freedom is morally defensible and economically beneficial for the vast majority of individuals—probably for all of them in the long run. Public policy should thus be based on a strong presumption in favour of economic freedom, to be overruled only in rare cases where an intervention benefits virtually everybody in society (as evaluated by the individuals themselves), not just a portion or even a majority. In case of doubt, economic freedom should prevail.

References

1. See also Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom: A Leading Economist’s View of the Proper Role of Competitive Capitalism, University of Chicago Press, 1962, especially chapter 1.

2. All historical data and estimates of economic growth rates come from the 2018 database of the Maddison Project. For the data, methodology, and sources, see Groningen Growth and Development Centre (GGDC), Historical Development, Maddison Historical Statistics, Releases, Maddison Project Database 2018. See also Jutta Bolt et al., “Rebasing ‘Maddison’: New Income Comparisons and the Shape of Long-Run Economic Development,” GGDC Research Memorandum 174, January 2018, pp. 13 and passim.

3. On the importance of social, political, and economic institutions, see Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty, Crown Publishers, 2012.

4. James Gwartney, Robert Lawson, Joshua Hall, and Ryan Murphy, Economic Freedom of the World: 2018 Annual Report, Fraser Institute, 2018. See also the accompanying online dataset. The index, which now covers 159 countries, measures economic freedom with a series of quantitative indicators related to the size of government, the rule of law and property rights, sound money, the freedom to trade internationally, and the volume of regulation. See Gwartney et al., pp. 3-5. Indexes and the indicators they are made of are, of course, subject to caution. But the same conclusions can be derived from the other major index of economic freedom: Terry Miller, Anthony B. Kim, and James M. Roberts, 2018 Index of Economic Freedom, Heritage Foundation, 2018.

5. GGDC, op. cit., endnote 2. On Hong Kong, see also “Meet the invisible hand behind Hong Kong’s rise,” The Economist, October 5, 2017.

6. GGDC, op. cit., endnote 2. See also Daron Acemoglu, Introduction to Modern Economic Growth, Princeton University Press, 2009, pp. 125-126.

7. Ronald Coase and Ning Wang, How China Became Capitalist, Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. For a review of the book, see Pierre Lemieux, “Getting Rich Is Glorious,” Regulation, Vol. 35, No. 4, Winter 2012-2013, pp. 58-61.

8. Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, op. cit., endnote 3, pp. 437-446.

9. This corresponds to a subsistence level of about $700 per year in 2011 US dollars. Since the amount is calculated at purchasing power parity, it takes into account lower prices (of non-tradable goods) in poor countries.

10. The World Bank, DataBank, Poverty and Equity, Poverty headcount ratio at $1.90 a day (2011 PPP) (% of population), 1981-2015, All countries.

11. For a summary of the economic research on the effect of social, political, and economic institutions on economic growth, see Daron Acemoglu, op. cit., endnote 3, pp. 123-137.

12. James Gwartney, Robert Lawson, Joshua Hall, and Ryan Murphy, op. cit., endnote 4, pp. 19-20.

13. Robert Nozick, Anarchy, State, and Utopia, Basic Books, 1974, p. 163.

14. James Gwartney, Robert Lawson, Joshua Hall, and Ryan Murphy, op. cit., endnote 4, p. 21.

15. Singapore, which is the second economically freest country in the EFW index, is ranked as only partly free (in the middle of the distribution) for political and civil rights by Freedom House’s Freedom in the World index. See Freedom House, Reports, Freedom in the World, Excel Data, 2018.

16. This is Milton Friedman’s argument; see endnote 1, Chapter 1 and especially p. 10.

17. Ibid.

18. On this, see Ronald Coase, “The Problem of Social Cost,” Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 3, October 1960, pp. 1-44; and James M. Buchanan and William Craig Stubblebine, “Externality,” Economica, Vol. 9, 1962, pp. 371-384.

19. The Gini coefficient measures the equality of the whole distribution of income, from 0 (totally equal) to 1 (one individual gets everything).

20. Data on Gini coefficients (here expressed on a scale from 0 to 100) are from The World Bank, GINI Index (World Bank estimate), 2018.

21. Vito Tanzi, Termites of the State: Why Complexity Leads to Inequality, Cambridge University Press, 2018. See also Pierre Lemieux’s review of this book in the Fall 2018 issue of Regulation (forthcoming).

22. See Gerald Auten and David Splinter, “Income Inequality in the United States: Using Tax Data to Measure Long-term Trends,” November 2017. Philip Magness summarizes the provisional results he has obtained with Vincent Geloso, John Moore, and Phil Schlosser on his personal blog: “Income inequality in the United States: it’s flatter than you probably realize,” May 1st, 2018. The argument that economic freedom has recently increased income inequality is found in Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, translated by Arthur Goldhammer, Harvard University Press, 2014. For a short critique, see David R. Henderson, “An Unintended Case for More Capitalism,” Regulation, Vol. 37, No. 3, pp. 58-61.

23. See, for example, Jeremy Greenwood et al., “Marry Your Like: Assortative Mating and Income Inequality,” American Economic Review, Vol 104, No. 5, 2014, pp. 348-353.

24. Branko Milanovik, “Global Income Inequality in Numbers: in History and Now,” Global Policy, Vol. 4, No. 2, May 2013, pp. 198-208.

25. Joan Robinson, Essays in the Theory of Employment, Basil Blackwell, 1947, p. 158.

26. See Anthony de Jasay, Social Justice and the Indian Rope Trick, Liberty Fund, 2014. For a preview and critique, see Pierre Lemieux, “The Valium of the People,” Regulation, Vol. 39, No. 1, 2016, pp. 53-56.

27. Friedrich A. Hayek, Law, Legislation, and Liberty, Vol. 1: Rules and Order, University of Chicago Press, 1973, notably Chapter 3. From the same author, see also The Road to Serfdom, University of Chicago Press, 1944.

28. Ibid., p. 56.