Wing Heavy: The Fees That Undermine the Competitiveness of the Airline Sector

Economic Note showing that the rents imposed on airport authorities, among other fees and taxes, weigh down the airline sector and raise the prices paid by passengers

The high cost of domestic air travel is largely due to the various fees the federal government charges airlines and airports, according to this MEI study. “Ottawa prefers to treat our airports as cash cows, rather than the essential transportation infrastructure that they are,” explains Gabriel Giguère, public policy analyst and author of the study.

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| Study shows how much more Canadians pay for flights due to tax (Sun Media Papers, December 7, 2023)

Des vols pour l’Europe au tarif de base de 2 $ en janvier (ICI Radio-Canada, December 7, 2023) Flights are more expensive in Canada than the U.S. due to tax: ‘Ottawa prefers to treat our airports as cash cows’ (National Post, December 7, 2023) |

Air travel much costlier due to federal fees (The Hamilton Spectator, December 11, 2023)

The cash grab that drives up airfares (TroyMedia, December 20, 2023) Airport rent raises airfares for Canadians (Skies, January 30, 2024) |

Interview (in French) with Gabriel Giguère (Midi Pile, KYK 95,7 FM, December 7, 2023)

Interview (in French) with Gabriel Giguère (Mario Dumont, QUB Radio, December 7, 2023) Interview (in French) with Gabriel Giguère (Benoit Dutrizac, QUB Radio, December 8, 2023) |

This Economic Note was prepared by Gabriel Giguere, Public Policy Analyst at the MEI. The MEI’s Taxation Series aims to shine a light on the fiscal policies of governments and to study their effect on economic growth and the standard of living of citizens.

The Canadian economy has been seriously affected by the pandemic over the past few years. Many sectors saw their contribution to GDP plummet during this period. Certain sectors like air transport, whose contribution fell by 36%, have yet to return to their pre-pandemic level of activity.(1) In a context in which the airline industry is subject to a heavy fiscal and regulatory burden, the federal government could contribute to the recovery of the sector by reducing airport rents, security fees, and the fuel tax.(2)

Eliminating Airport Rents

According to the current regulatory framework—which dates back to 1992—the federal government delegates the management of Canadian airports(3) to non-profit organizations called airport authorities. The framework stipulates that these authorities will pay rent to the government based on the airport’s gross revenues.(4) In total, 26 airports are managed by these organizations and belong to the National Airports System (NAS).(5) These are the busiest airports in the country, like the Montréal-Trudeau and Toronto Pearson airports.

The annual rent payments represent a heavy burden for NAS airports, which hurts the sector as a whole, starting with the airport authorities but also including airlines and passengers. Indeed, rent can absorb up to 12% of an airport’s revenues, as is the case for the largest of them.(6) This financial pressure due to elevated rents directly limits the ability of airport authorities to invest in their own infrastructure.

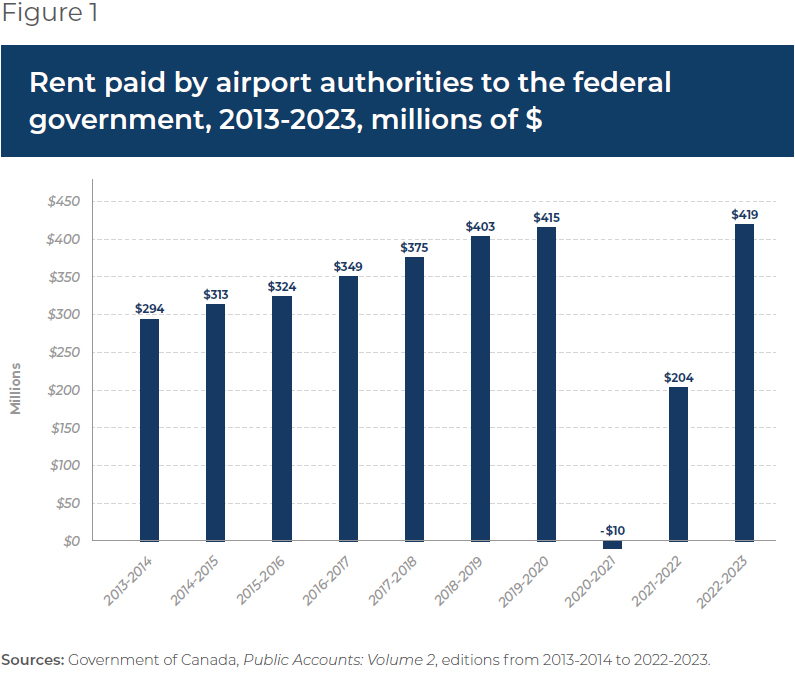

For the 2022-2023 fiscal year, the rents paid to the federal government amounted to $419 million, an increase of 42.5% in just 10 years (see Figure 1).(7) During the decade from 2013 to 2023, NAS airports paid over $3 billion to the government, in spite of the reduction in rental revenues during the two years that were seriously affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, the airline industry as a whole experienced a drastic decline in its activities, which led the government to suspend rent payments for the 2020-2021 fiscal year.(8)

Compared to the billions of dollars it collects in rent, the federal government invests little, if anything, in maintaining airport infrastructure, especially when it comes to the large NAS airports. An annual average of around $32 million was invested from 2013 to 2020 through the federal Airports Capital Assistance Program (ACAP), which represents only around 9% of the average rental revenues collected over the same period.(9) Only a very small portion of ACAP funds are paid to a few small NAS airports, with the majority going to airports that do not pay rent.(10)

Worse still, the busiest airports receive no ACAP funding, while they are the ones that pay the lion’s share of federal rental revenues. For instance, Pearson and Montréal-Trudeau together accounted for over 55% of the total value of rents collected in 2022.

Compared to the billions of dollars it collects in rent, the federal government invests little in maintaining airport infrastructure.

In order to ensure the maintenance of the infrastructure under their management, the non-profit airport authorities—having been deprived of funds paid in rent to the federal government—impose airport improvement fees, which are charged directly to passengers on their plane tickets. These fees notably rose from $25 in December 2017 to $35 in February 2021 at Montréal-Trudeau airport, and will increase to $40 in March 2024,(11) while at Pearson airport, they rose from $5 before the pandemic to $35 in 2023.(12) The rents imposed on the airport authorities in order to increase government revenues therefore act as a tax imposed on travellers.

Decision makers should have taken advantage of the temporary pause in rent collection in 2020-2021 to review their policy and implement a permanent change. The post-pandemic context makes these issues relevant once again. Already in 2013, a senate committee had recommended eliminating rental payments from the airport authorities to the federal government.(13) Its report also highlighted the need to transfer airports to the airport authorities, and even to privatize them, thereby allowing them to invest more in infrastructure. Successive governments have failed to follow up on this recommendation.

Reducing the Air Travellers Security Charge

The air travellers security charge is another fee that weighs down the sector. It was introduced following the September 11, 2001 attacks. In theory, this fee serves to finance the operations of the Canadian Air Transport Security Authority. The amount varies by type of flight: currently, it is $7.48 for a one-way domestic flight and $25.91 for an international flight.(14)

In its 2023-2024 budget, the federal government announced an increase in the air travellers security charge starting May 1st, 2024.(15) According to the Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer, this would be an increase of around 33%, which would add $1.2 billion to federal revenues over the next four fiscal years.(16)

For all types of flights (one-way domestic, round-trip domestic, or international), security charges are lower in the United States.

By comparing Canada’s air travellers security charges to those in effect in the United States, we find that the charges paid by American travellers are lower, especially if Canada’s upcoming increases are taken into account. Indeed, for all types of flights (one-way domestic, round-trip domestic, or international), security charges are lower in the United States.(17) For an international flight, a Canadian traveller will pay a fee of $34.42 as of May 1st, 2024, while an American traveller will pay a maximum of $15.30 (in Canadian dollars).(18) The planned increase in Canada would thus lead to a difference between the two countries of nearly $20 per ticket, undermining the competitiveness of the Canadian airline sector.

The government must start looking at alternatives, and request a detailed study of the needs of the Canadian Air Transport Security Authority in order to consider reducing security charges instead of increasing them.

Reducing the Fuel Tax

In addition to security fees and rents that are too high, there is the federal excise tax on fuel, in effect since 1985, which also increases the prices of plane tickets.(19) Although this tax is only 4 cents per litre of aviation fuel, this represents a little over $900 million paid into federal government coffers by the airline sector over the past decade.(20)

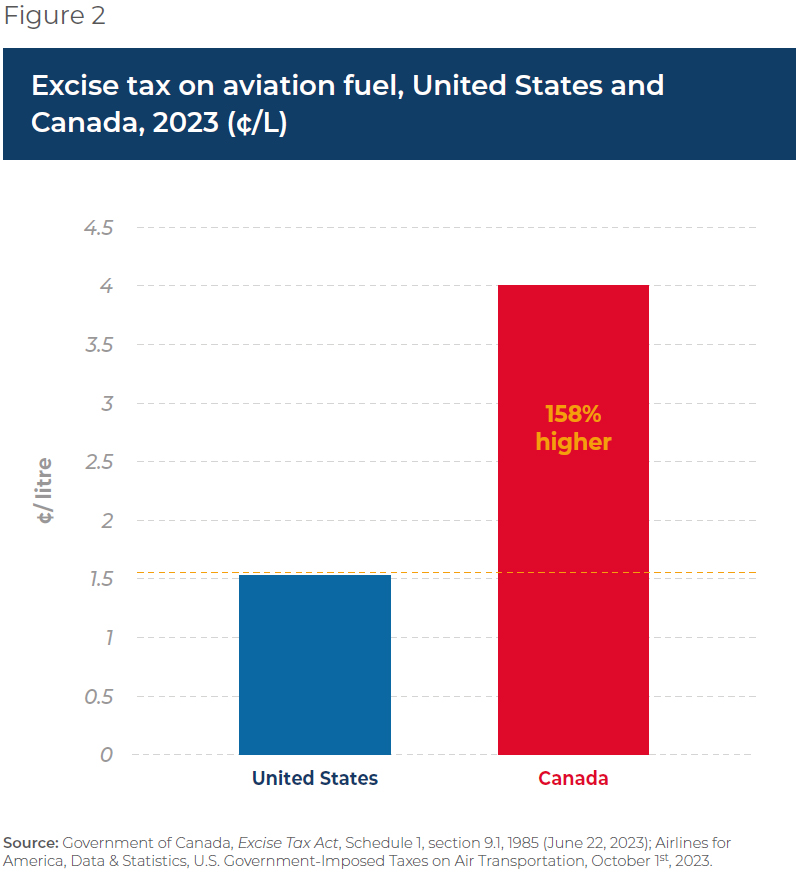

The American government also imposes a tax on aviation fuel.(21) It is just 4.3 cents US per gallon, however, or 1.55 cents CA per litre of fuel.(22) As the Canadian excise tax on fuel is 158% higher than the American tax (see Figure 2), our airline sector is disadvantaged in this regard as well, which favours American airports just south of the border that attract Canadian travellers.

The carbon tax on fuel,(23) or fuel charge, is another aspect to consider. It applies to all types of fuel, including kerosene, used in most commercial airplanes. For the moment, flights between provinces subject to the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act are exempt from this tax.(24) The federal government would do well to maintain this exemption so as not to further undermine the attractiveness of Canadian destinations for domestic flights.

The maintenance of this exemption, combined with a reduction in the fuel tax to bring it down to the level in effect in the United States, would help increase the competitiveness of the Canadian airline sector.

Conclusion

The current fiscal and regulatory framework penalizes Canadian travellers, who pay more for their plane tickets due among other things to airport rents and other elevated fees. This framework also undermines the competitiveness of our airports compared to American airports just south of the border.

Canadian travellers pay more for their plane tickets due among other things to airport rents and other elevated fees.

In order to reduce the burden imposed on travellers and improve the competitiveness of our airline industry, the federal government should look at abolishing the rents imposed on airport authorities and consider all options for reducing the other fees and taxes that weigh down the sector and raise the prices paid by passengers.

Despite a fairly minor loss of revenues for the federal government compared to its total revenues, these changes would lead to increased economic activity that would benefit the sector and the Canadian economy as a whole, which in the long run would offset those reduced tax revenues.(25)

References

- Author’s calculation. Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0434-01: Gross domestic product (GDP) at basic prices, by industry, monthly (x 1,000,000), 2023.

- This analysis will examine these different charges based among other things on the approach adopted in a 2006 MEI publication. See Stéphanie Giaume and Martin Masse, “How to Make the Canadian Airline Industry More Competitive,” Economic Note, MEI, November 2006.

- Library of Parliament, Airport Governance Reform in Canada and Abroad, Publication No. 2017-17-E, May 4, 2017, p. 2.

- Standing Senate Committee on Transport and Communications, One Size Doesn’t Fit All: The Future Growth and Competitiveness of Canadian Air Travel, Canadian Senate, April 2013, p. 15.

- Government of Canada, The Canadian Transportation System – Highway and air infrastructure, May 8, 2018.

- Alexandre Moreau, “The Charges and Taxes That Undermine the Competitiveness of Canadian Airports,” Economic Note, MEI, June 2016, p. 2.

- Author’s calculations. Government of Canada, Public Accounts: Volume 2, editions from 2013-2014 to 2022-2023.

- Lina Dib, “Ottawa ne réclamera pas paiement des loyers aux aéroports,” Le Devoir, March 31, 2020.

- Author’s calculations. Government of Canada, op. cit., endnote 7. The pandemic years were removed, given the particular context that seriously affected the airline sector. However, including the pandemic and post-pandemic years, the ACAP reinvested the equivalent of 16% of the government revenues from rent payments.

- Government of Canada, Airports Capital Assistance Program: Recently funded projects, November 14, 2023.

- Martin Jolicoeur, “Aéroports de Montréal : hausse importante des frais aux passagers,” Le Journal de Montréal, June 18, 2020; Aéroport de Montréal, “Public Notice,” October 23, 2020; La Presse canadienne, “Hausse des frais à l’aéroport Montréal-Trudeau dès le printemps,” La Presse, December 1st, 2023.

- La Presse canadienne, “Pourquoi les frais d’aéroport augmentent à travers le pays?” Les Affaires, March 6, 2023.

- Standing Senate Committee on Transport and Communications, op. cit., endnote 4, p. 12.

- Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer, “Increasing the Air Travellers Security Charge,” May 9, 2023, p. 1.

- Government of Canada, Budget Implementation Act, 2023, No. 1, section 127, June 22, 2023.

- Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer, op. cit., endnote 14, p. 1.

- Transportation Security Administration (USA), Security Fees, consulted October 23, 2023.

- Author’s calculation: $11.20 (US) x 1.3657 = $15.30. Bank of Canada, Daily exchange rates, consulted October 12, 2023.

- Government of Canada, Excise Tax Act, Schedule 1, section 10.1, 1985 (June 22, 2023).

- Government of Canada, op. cit., endnote 7. The pandemic slowdown did entail a reduction in revenues, from $108 million in 2019-2020 to $56 million in 2020-2021. This downward trend was only temporary, though, and 2022 revenues were $117 million.

- Airlines for America, Data & Statistics, U.S. Government-Imposed Taxes on Air Transportation, October 1st, 2023.

- Author’s calculation: (4.3¢ US x 1.3657) / 3.785412 = 1.55¢ / litre. Bank of Canada, Daily exchange rates, consulted October 12, 2023.

- Government of Canada, Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act, Part 1, June 21, 2018 (July 1st, 2023).

- Government of Canada, Definitions related to the fuel charge, Covered air journey and Excluded air journey, August 8, 2023.

- Alexandre Moreau, “Air Transport: High Taxes and Fees Penalize Travellers,” Economic Note, MEI, June 2018, p. 4.