The Winning Conditions for Quebec’s Mini-Hospitals

Research Paper explaining the conditions that need to be met in order to ensure that Quebec’s mini-hospitals improve access to frontline services, reduce emergency room overcrowding, and complement the existing supply of services

The success of the proposed mini-hospitals run by independent entrepreneurs rests largely on activity-based funding and the flexible management of human resources, according to this Montreal Economic Institute study.

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| Il faut aller de l’avant avec les mini-hôpitaux (La Presse, June 20, 2023) | Interview (in French) with Emmanuelle B. Faubert (Marceau le midi, BLVD 102.1, June 15, 2023)

Interview (in French) with Emmanuelle B. Faubert (Billet de retour, CPAM 1410, June 15, 2023) |

Interview with Emmanuelle B. Faubert (CTV News Montreal at Noon, CFCF-TV, June 20, 2023)

Interview with Emmanuelle B. Faubert (Global News, Global TV, June 22, 2023) |

This Research Paper was prepared by Maria Lily Shaw, Associate Researcher at the MEI, and Emmanuelle B. Faubert, Economist with the MEI. The MEI’s Health Policy Series aims to examine the extent to which freedom of choice and entrepreneurship lead to improvements in the quality and efficiency of health care services for all patients.

Highlights

The Quebec health care system’s problems and challenges have persisted for far too long. In order to address these shortcomings, the government plans to soon deliver on one of its electoral promises, namely the addition of two private mini-hospitals operating within the health care system. The ultimate goal of these mini-hospitals is to improve Quebecers’ access to frontline services, to reduce emergency room overcrowding, and to complement the existing supply of services. However, if we want to see the potential benefits of introducing these mini-hospitals, certain conditions will need to be established in order to make the project a success.

Chapter 1 – Create an Opening in the Current System for Competition

- Mixed hospital systems represent the norm in industrialized countries, where universal coverage and the private sector exist side by side.

- The case of Quebec, and by extension that of Canada, is an international anomaly with its near total absence of private, for-profit facilities.

- It is not the mere presence of the private sector that improves access to care and efficiency, but rather the opening up to entrepreneurship, flexibility, and the injection of competition and innovation that ensue.

- It is important to integrate market mechanisms that include rewards for providers, their administrators, and their employees, so as to encourage them to make decisions that improve the services they offer.

- The mini-hospitals should serve as environments that foster innovation, where new techniques and administrative models will be put to the test.

Chapter 2 – Ensure Adequate Funding

- For the moment, each patient treated in a hospital represents a cost for the facility, since the budget is established independently of the number of patients the hospital treats in the current year.

- Activity-based funding mechanisms encourage efficiency and innovation, but also cost control and accountability, since hospitals receive a fixed price per intervention, regardless of the actual amount spent to treat the patient.

- A key element in the funding of mini-hospitals is the budgetary envelope they will be provided with, both in terms of operating expenses and in terms of fixed assets. Without the potential to make sufficient profits, no entrepreneur will be interested in investing.

- Mini-hospitals should be authorized to use their residual or excess capacity in order to serve a clientele that is not covered by the RAMQ, but they will only be able to do so if the prohibition on mixed medical practice is lifted.

Chapter 3 – Allow Flexible Management

- It is indispensable for quality control to be objective and independent, in the spirit of respecting the opening up of the current system to competition. In this way, the risk of excessive rigidity resulting from an improper assessment of the quality of care would be reduced as much as possible.

- Not imposing the public health care sector’s collective agreements on the mini-hospitals would create an environment that is more conducive to efficiency and innovation.

- The administrators of the mini-hospitals should have flexibility in the management of the supply of auxiliary services, such as security, maintenance, and the procurement of food, computer software, medical equipment, etc.

- Another way to ensure greater efficiency is to allow administrators full latitude to limit the paperwork that currently paralyzes health professionals. Doctors in Canada devote nearly 19 million hours a year to administrative activities.

Chapter 4 – Remove the Most Restrictive Regulatory and Legislative Obstacles

- The prohibition against doctors practising in both the public and the private systems when it comes to medical acts insured by the RAMQ is set out in Quebec’s Health Insurance Act, but mixed practice is not expressly prohibited by the Canada Health Act.

- By authorizing mixed practice, Quebec would join the many industrialized countries, as well as the four Canadian provinces of Manitoba, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and New-foundland and Labrador, that do not prohibit it.

- International experience shows that doctors working in countries that authorize mixed practice do not devote less time to taking care of patients in the public system than their counterparts practising solely in the public sector.

- The number of students admitted each year into the different medical school programs is too small to meet the growing needs of the population. Facilitating the recognition of the skills of professionals from other provinces and countries could also help resolve the current shortage.

- Allowing the mini-hospitals to keep their patients overnight could favour the development of their capacities so as to diversify the types of services they offer, and thus further relieve the pressure on public hospitals.

- The staffing plans for the regions where the mini-hospitals will be located will have to reflect the addition of a health care facility that will disburse a wide range of services requiring family doctors and medical specialists.

The construction of two new private mini-hospitals in the province has the potential to provide Quebecers with substantial benefits. For this potential to be realized, however, several conditions must be met in order to ensure the project’s success. These conditions are crucial to creating an environment conducive to innovation and efficiency, all while guaranteeing quality of care and equitable access for patients. Each condition can be fulfilled without violating the Canada Health Act or compromising the universality of the Quebec health care system. These are achievable conditions already present in numerous industrialized countries with universal health care.

INTRODUCTION

The Quebec health care system’s problems and challenges have persisted for far too long. For example, 158,507 patients were waiting for day surgery as of April 2023. Of this number, 31% had been waiting for over six months.(1) Moreover, the median length of stay in an emergency room has grown in recent years. It reached 5 hours and 11 minutes in 2022, a 40-minute increase (14%) in four years. Worse still, the number of patients on stretchers having waited more than 24 hours in an emergency room grew by 50%, reaching almost 210,000 people, or nearly one patient in four.(2)

In order to address these shortcomings, the Quebec government plans to soon deliver on one of its electoral promises, namely the addition of two private mini-hospitals operating within the health care system. This ambitious project must be commended, as it has the potential to encourage competition between providers and greater freedom of choice for patients in the hospital system, all while maintaining universal coverage for medically necessary treatment financed by the government.

The median length of stay in an emergency room reached 5 hours and 11 minutes in 2022, a 40-minute increase (14%) in four years.

However, if we want to see the potential benefits of introducing these mini-hospitals, certain conditions will need to be established in order to make the project a success. Indeed, we must avoid reproducing the same shortcomings observed in hospitals today. Moreover, certain legal prohibitions currently in effect would prevent these new facilities from developing their full potential, were they to be left in place, notably those that affect mixed practice and the hospitalization of patients. This paper will present all of these aspects that need to be avoided, as well as the conditions to be put in place in order to ensure the successful operation of the mini-hospitals.

Outlines of the Mini-Hospitals Project

Before presenting the conditions required for the success of the mini-hospitals, it is important to inventory what we have learned so far(3) about this Quebec government project.

First, the ultimate goal of these mini-hospitals is to improve Quebecers’ access to frontline services, to reduce emergency room overcrowding, and to complement the existing supply of services.(4) Furthermore, while treatment will be covered by the Régie de l’assurance maladie du Québec (RAMQ), the private sector will take care of running the facilities.(5) The two mini-hospitals will be built by 2025 in the Quebec City region and in Eastern Montreal, and they will specialize in pediatrics and geriatrics, respectively.(6)

These facilities will be equipped with an emergency room for minor cases,(7) open 24 hours a day. Patients will be directed to these facilities after secondary triage conducted by ambulance technicians or through 8-1-1 and the digital Primary Care Access Point.

The goal of these mini-hospitals is to improve Quebecers’ access to frontline services, to reduce emergency room overcrowding, and to complement the existing supply of services.

In addition to ambulatory emergency services, the mini-hospitals will offer interdisciplinary professional services and ensure that each patient is seen by the appropriate health professional.(8) Interdisciplinary teams will include RAMQ-participating family doctors, specialized nurse practitioners, social workers, psychologists, physiotherapists, and other health professionals. There will also be outpatient clinics and laboratory services (radiology, ultrasound) in order to provide a wide range of treatments. Stretchers for observation of up to 12 hours as well as stretcher-beds for observation, investigation, and short treatments for stays of 24, 48, and 72 hours will be available. However, patients needing long-term hospitalization will not be treated in these mini-hospitals.(9) In fact, the government does not plan to include in these mini-hospitals the capacity to carry out surgeries in an operating room.(10)

The cost of their construction was estimated at $35 million each.(11) This amount, however, will be entirely financed by the private sector.

Two calls for expressions of interest inviting potential partners to make their interest known(12) were issued in March 2023 in order to specify the general conditions, the clinical concept, and the terms of the project. More details about the project are still forthcoming, for instance regarding the method of financing or the number of stretchers that will be available.

CHAPTER 1 – Create an Opening in the Current System for Competition

1.1 The Presence of Private, For-Profit Facilities Is the Norm Elsewhere in the World

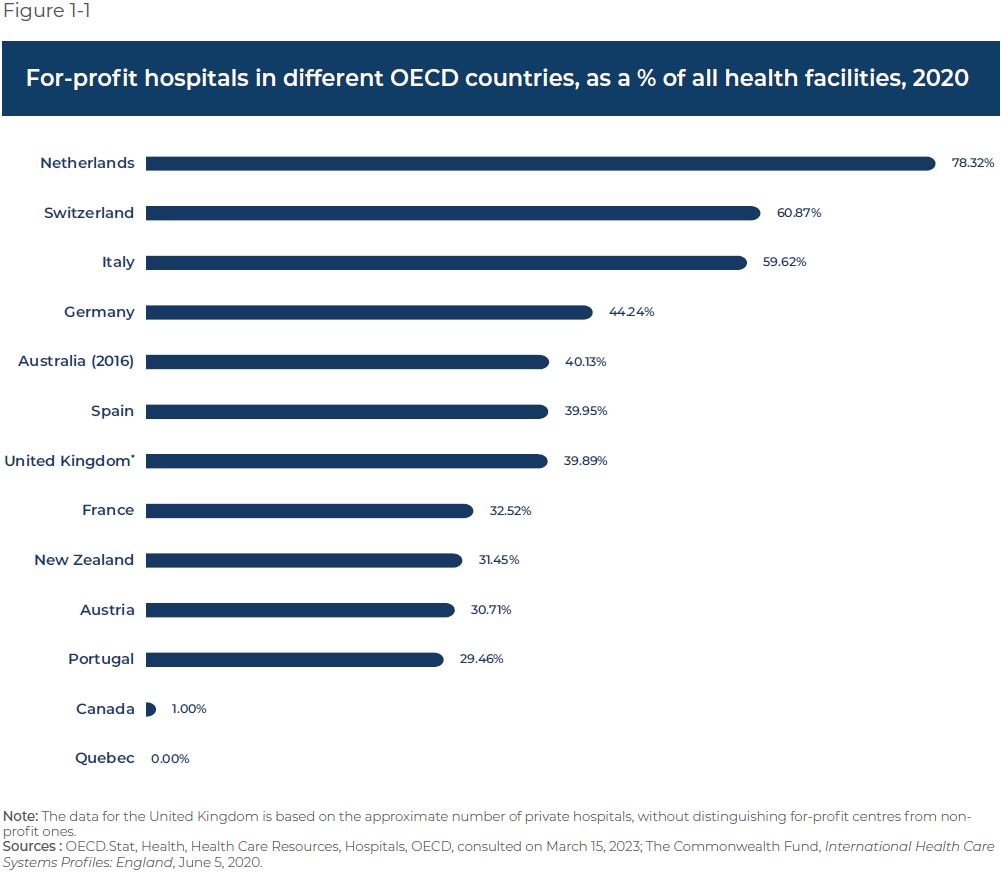

The private mini-hospitals project may seem ambitious, but it is a well-established practice in many countries (see Figure 1-1). Indeed, mixed hospital systems, with private sector participation, represent the norm in industrialized countries, where universal coverage and the private sector exist side by side. These often feature three different kinds of hospitals:(13)

- Public hospitals

- Private, not-for-profit hospitals

- Private, for-profit hospitals, like the current mini-hospitals project

In France, for example, all hospitals, regardless of type, primarily use activity-based funding covered by the public purse.(14) The three kinds of hospitals provide short-term medical care, surgical care, and obstetric care, but with different specializations. Public hospitals provide two-thirds of short-term medical treatment capacity and provide a wider range of surgical interventions than for-profit hospitals. Although private, for-profit hospitals also provide such services and carry out more than half of all surgeries, they tend to focus on a narrower range of technical procedures (like invasive diagnostic procedures) and specialize in routine procedures with short and predictable hospital stays. Around two-thirds of all ambulatory surgeries are provided by for-profit hospitals. Surgical interventions carried out in the non-profit private sector, for their part, are mainly related to the treatment of cancer.(15)

As shown in Figure 1-1, the case of Quebec,(16) and by extension that of Canada, is an international anomaly with its near total absence of private, for-profit facilities. The significant participation of such facilities is indeed the norm in industrialized countries with universal coverage health care systems.

1.2 The Benefits of Opening Up to Private Sector Competition

The important thing to remember about countries that have adopted mixed health care systems is that it is not the mere presence of the private sector that improves access to care and efficiency, but rather the opening up to entrepreneurship, flexibility, and the injection of competition and innovation that ensue in a system otherwise under a public monopoly. In other words, the benefits stem from the fact that there is no longer one single care provider, but rather a range of different providers, regardless of whether administration is private, community-based, or non-profit.

These benefits include a stimulus for administrative models and better ways of doing things in terms of health care since providers make an effort to differentiate themselves by proposing new and innovative treatments and services. Competition works when this differentiation has the effect of attracting more patients, more revenues, and therefore more success (in the form of greater profits for some providers, or other positive effects for others) to the most efficient and innovative facilities. It is therefore important to integrate market mechanisms that include such rewards for providers, their administrators, and their employees, so as to encourage them to make decisions that improve the services they offer, which is something that almost never happens in a monopolistic system with uniform practices and centralized decision making.

Mixed hospital systems represent the norm in industrialized countries, where universal coverage and the private sector exist side by side.

Competition thus entails an improvement in the quality of care, to the benefit of patients. As for health professionals, they have a choice between different employers which have an incentive to offer them attractive working conditions, such as flexible shifts, in order to entice or retain them. Otherwise, they have the option of changing employers, which is not the case in a monopolistic system like the one that currently exists in Quebec.

It is important to remember that Quebec already has several examples that illustrate the benefits of openness to competition (see Box 1-1). In the same spirit, the mini-hospitals should serve as environments that foster innovation, where new techniques and administrative models will be put to the test, both in terms of medical operations and the organization of related tasks.

* * *

Box 1-1 – Two successful Quebec examples of opening health care up to competition

The case of hygienists since 2020

As of 2020, dental hygienists are no longer required to work for a dentist. Hygienists can therefore work for themselves, either setting up their own office or offering mobile services, without the supervision of a dentist. It is estimated that between 15 and 20 private clinics of this kind have since opened their doors in the province. This provides an alternative as much for patients needing preventive care as for hygienists in terms of their employer.(1) Moreover, these new clinics expand access to the essential services provided by hygienists, and at a lower cost to patients since there is no more need to systematically pay two professionals as was the case up until 2020, namely the dentist and the dental hygienist. Indeed, competition between hygienists in Ontario led to a 30% reduction in the cost schedule for oral health services for patients.(2) The greater mobility of hygienists also facilitates care provision for at-risk clientele such as the elderly, those with reduced autonomy or mobility, and people living in remote regions.(3)

Specialized Medical Centres

Specialized Medical Centres (SMCs) are another example of openness to competition. There are 73 of them in the province as of April 2023.(4) SMCs aim to increase the surgical capacity of the health care system and shorten wait lists for non-urgent operations that do not require hospitalization. All SMCs are administered independently, and most (50) of them are so-called participating SMCs,(5) whereby the provision of services and doctors’ fees are covered by the RAMQ. While it is true that from the point of view of care providers, SMCs represent another potential employer, for patients, surgical services covered by the RAMQ are only accessible to them in certain cases after being on a waiting list for more than six months.(6) It is only at this stage that the hospital having prescribed the operation offers the patient the option of being operated in an SMC with which the hospital has an agreement.(7) (See Annex A for more information about SMCs.)

1. Cimon Charest, “Deux cliniques d’hygiénistes dentaires dans l’Est-du-Québec,” TVA Nouvelles, February 8, 2022.

2. Government of Canada, Competition Bureau Canada, How we foster competition, Promotion and advocacy, Competition and the common cold, January 20, 2022. Similar studies for the case of Quebec have not yet been conducted, in part because the autonomous practice of dental hygienists was only authorized in 2020. Nonetheless, it is reasonable to think that the effect in Quebec is similar to that observed in Ontario.

3. Frederic Khalkhal, “Les hygiénistes dentaires, une solution abordable,” Le Journal de Chambly, December 11, 2022.

4. Department of Health and Social Services of Quebec, Professionnels, Permis, Obtention d’un permis de centre médical spécialisé (CMS), Liste des centres médicaux spécialisés ayant reçu un permis, April 5, 2023.

5. Nearly a third of SMCs, commonly called non-participating SMCs, are completely detached from the public system, which is to say that the doctors who work for them do not participate in Quebec’s health insurance plan and patients must pay out of pocket the costs associated with the services they receive.

6. Nadia Benomar and Marie-Hélène Jobin, Portrait des tendances et des pratiques de la chirurgie ambulatoire, Pôle santé HEC Montréal, June 2021, p. 11.

7. Ibid., p. 8.

* * *

CHAPTER 2 – Ensure Adequate Funding

2.1 Activity-Based Funding

Quebec’s hospitals are going through a period of transformation in terms of how they are financed. It is expected that by the end of 2023, 25% of hospitals in the province will be funded on an activity basis at rates that will entice public and private facilities to compete in order to obtain the best price for a surgical intervention.(17)

For the moment, hospitals are financed according to fixed budgets determined according to the volume of activity the previous year, plus a certain percentage to adjust for inflation.(18) While the government intends to gradually impose activity-based funding on all Quebec hospitals, it is not yet known if this funding mechanism will also be applied to the mini-hospitals.

It is clear that fixed budgets have several shortcomings that would undermine the success of the mini-hospitals. For example, each patient treated in a hospital represents a cost for the facility, since the budget is established independently of the number of patients the hospital treats in the current year. This has the effect of reducing the incentive to improve access to services, since each additional patient consumes more of the hospital’s budget.

Activity-based funding mechanisms encourage efficiency and innovation, but also cost control and accountability.

A facility’s performance is not taken into consideration either when determining its fixed budget, which eliminates any incentive to innovate and improve the efficiency of its administration. Less efficient hospitals therefore keep underperforming without suffering any consequences, while more successful hospitals have to manage their budgets more carefully, since their funding does not increase based on the number of patients treated. There is also no benefit to maintaining their performance level.

Finally, fixed budgets make it difficult to respond to a sudden increase in demand and do not encourage transparency, since administrators have no incentive to keep a close eye on expenditures or to identify potential sources of wasted resources.

An activity-based funding mechanism, in contrast, alleviates several of the shortcomings of fixed budgets. If the mini-hospitals were funded this way, they could reap the benefits of this type of funding that is focused on the patient.

Activity-based funding consists of reimbursing treatment centres on the basis of a system of classification that standardizes the costs of patient treatments. Hospitals receive a fixed amount for each patient they treat based on the operation performed and the severity of the medical problems involved. Activity-based funding mechanisms thus encourage efficiency and innovation, but also cost control and accountability, since hospitals receive a fixed price per intervention, regardless of the actual amount spent to treat the patient. As a result, if a hospital can safely treat a patient at a lower cost than the set rate, the facility can generate a profit. On the other hand, the hospital will suffer a loss if it cannot provide the service at the determined rate, which will motivate it to become more efficient and encourage accountability.

In light of these substantial benefits, it is no surprise that many OECD countries with universal health care systems have adopted activity-based funding in recent decades.(19)

However, most of these countries actually have a mixed payment system that mitigates some of the drawbacks of activity-based funding. Indeed, there can be a misalignment between activity-based payments and controlling hospitals’ volumes and expenditures. Since the funds follow the patient, hospitals can have an incentive to treat a greater number of patients and carry out more interventions than are medically necessary, thus inflating the funding they receive for those activities.

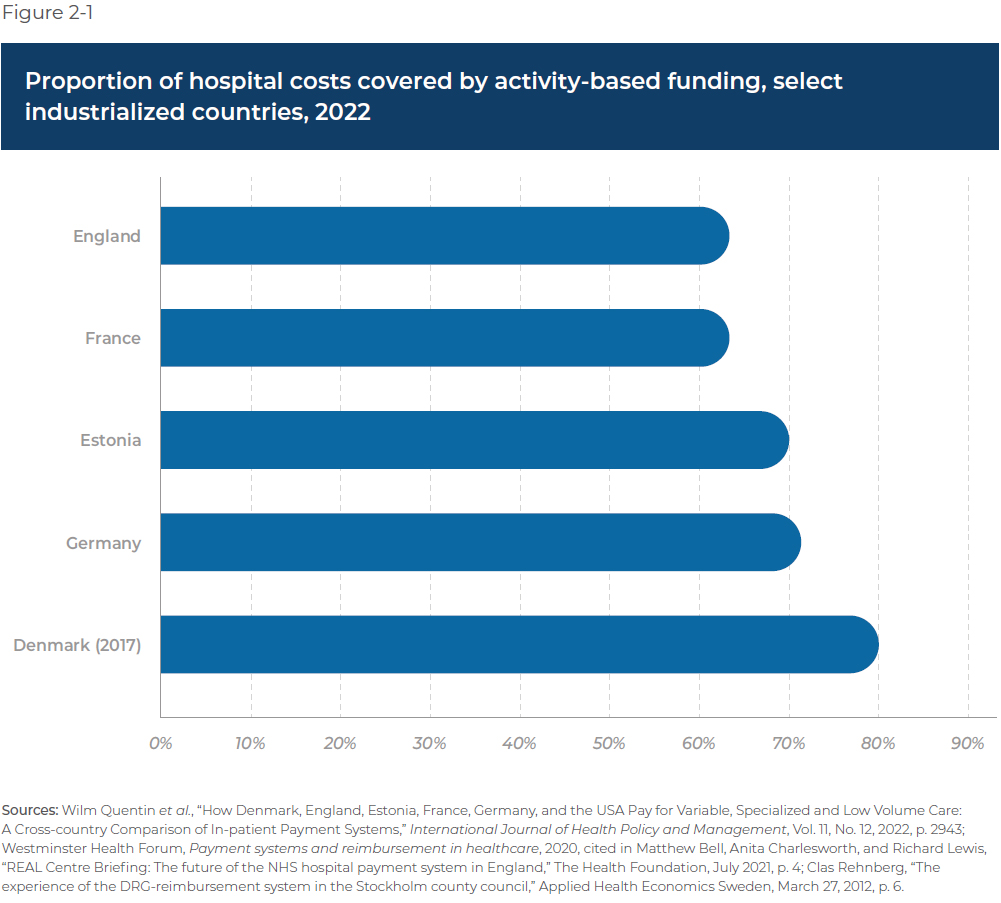

Another drawback of this method of funding is that it encourages the early discharge of patients and increased workloads for staff, which can lead to a reduction in the quality of care. The case of an administrative rate set at an artificially low level by the public authorities is a good example. Therefore, in countries like England and Denmark, from 63% to 80% of operations are funded with activity-based payments (see Figure 2-1), the rest being funded using methods like fixed payments that cover additional costs related to severe cases, payments for performance, and payments based on patient choice.(20) Quebec will have to strike a balance between these contrary incentives that will meet its particular needs and the special features of its mini-hospitals project in order to allow for activity-based funding that is adequate and sufficient.

2.2. Providing a Sufficient Budgetary Envelope

A second key element in the funding of mini-hospitals is the budgetary envelope they will be provided with, both in terms of operating expenses and in terms of fixed assets.

A Sufficient Operating Budget

The government must provide for a budget dedicated to the daily activities of the mini-hospitals that is sufficient to cover their volume of activity. Operating costs generally include salaries, administrative costs, supplies, and other expenses related to activities in the current period.(21) This is a particularly important issue in the context of activity-based funding, because a quota, whether established based on the number of patients or by capping activity-based financing, would essentially represent a new form of care rationing. This could force the hospitals to refuse patients, thus limiting the positive impact of the mini-hospitals on the hospital network.

Imposing a limit on the treatments provided in the mini-hospitals because of a lack of funding could eliminate the productivity gains stemming from their entrepreneurial administration (see Section 3.1 below). The government must therefore guarantee flexibility in the administrators’ budgets to avoid a suboptimal use of resources and so that their investments will pay off. A facility that reaches its quota of interventions will have no incentive to innovate in order to increase its capacity to treat more patients, even if its resources are under-utilized.

The target utilization rate for operating rooms is 85%, but only 30% of the province’s hospitals achieved this objective in 2017-2018.

The example of operating rooms in the public hospital network is telling.(22) The target utilization rate for operating rooms is 85%, but only 30% of the province’s hospitals achieved this objective in 2017-2018, well before the pandemic. The reasons for this under-utilization are many: labour shortages, lack of equipment, and lack of financial support.(23) Sufficient funds must therefore be provided to ensure the continual use of facilities, especially if we want to avoid finding ourselves with new, but empty, medical infrastructure.

A Capital Assets Budget

The second budgetary envelope that should not be underestimated concerns the financing of fixed or capital assets for the new mini-hospitals. Fixed asset budgets typically cover expenditures that will be useful beyond the current period, including costs for equipment, construction, rent, maintenance, and renovation, as well as the amortization of these costs.

There are different options for financing capital assets, such as including fixed asset costs in the rates for activity-based funding. Another, partial option would be to allow for the use of residual capacity to treat patients not covered by the RAMQ (see Section 2.3 below). Finally, we can opt for direct financing, which consists of reimbursing private entrepreneurs for the construction and maintenance of the building for the long term, and so on.

What is certain is that those who run the mini-hospitals have to be able to cover their fixed asset costs, and to do so with a certain flexibility. Without the potential to make sufficient profits, no entrepreneur will be interested in investing. The government must give such financing due consideration as it develops the project.

Following the Family Medicine Group (FMG) Model?

Many details are still unknown, and the goal of the government’s calls for expressions of interest is notably to clarify some uncertain aspects of the project, such as those concerning financing. In its initial conception of the project, the government put forward the idea that the mini-hospitals would constitute an amalgam of family medicine groups (FMGs) and conventional hospitals, which would adopt a funding mechanism similar to FMGs.(24) Under this funding model, which is albeit complex, a portion of the public funding of FMGs depends on the number of patients registered. As for super clinics, which are FMGs offering rapid primary care services to patients without a family doctor, they receive funding based on the number of consultations granted in this context as an outpatient clinic.(25) In both cases, this funding method is akin to activity-based funding, an important condition for the success of the mini-hospitals, and could serve as a model after having been adapted to their operation.

2.3 Not Prohibiting the Use of Residual Capacity as an Additional Source of Funds

According to current plans, it is only operations covered by the RAMQ that will take place in the mini-hospitals. However, it would be advantageous to allow them to make full use of their residual capacity by performing procedures outside of the RAMQ plan. By having this freedom to use their equipment and infrastructure, the mini-hospitals would have access to an additional source of revenue, thus reducing their dependence on public funds.

For example, the physical premises and certain other resources could be rented for private purposes, at a price to be determined by the two parties (the mini-hospitals and the doctors). Similarly, the mini-hospitals should be authorized to use their residual or excess capacity in order to serve a clientele that is not covered by the RAMQ, such as private patients, foreign students, foreign workers, diplomats, and so on.

In terms of the size of this potential pool of patients, the Institut du Québec estimated in 2022 that there were 111,600 foreign students(26) and temporary foreign workers in the province.(27) This is therefore a considerable population that could benefit from treatment in the mini-hospitals through the use of their residual capacity. However, the mini-hospitals will only be able to use their residual capacity in this way if the prohibition on mixed practice is lifted (see Chapter 4). More precisely, Quebec’s Health Insurance Act(28) prevents doctors who participate in the public system from working outside it when it comes to medical services already covered by the RAMQ. This section of the law must therefore be modified so as to give doctors the freedom to treat patients in the private and public sectors simultaneously.

Mini-hospitals should be authorized to use their residual or excess capacity in order to serve a clientele that is not covered by the RAMQ.

Quebec could also conceivably follow the example of the United Kingdom, which since the late 1990s has delegated to the private sector the responsibility of designing, building, and running hospitals for the National Health Service (NHS).(29) In the context of these agreements, private companies generally fund the construction of hospitals, and this interest-bearing debt is amortized over several decades by the NHS.(30) The risks associated with construction delays, cost overruns, and asset maintenance are therefore transferred to private sector partners.(31) These hospitals remain providers of health care treatments covered by public funds with the same codes of ethics for caregivers. This is an example to consider in order to offer Quebec entrepreneurs the potential to earn a return on their investments.

Along similar lines, the mini-hospitals could take inspiration from the funding method of the province’s participating Specialized Medical Centres (SMCs). Indeed, the amounts these facilities receive for performing day surgeries for the public system are negotiated with the health care facilities and include a profit margin.(32) The mini-hospitals, through their activity-based financing, could also receive amounts adjusted according to the agreements between the government and the companies that will be entrusted to build them.

CHAPTER 3 – Allow Flexible Management

The entity that will be in charge of the administration of the mini-hospitals is not yet known, but it could be an independent management company. Administrators will have to respect rigorous standards regarding treatment quality, but beyond these obligations, they should have some latitude regarding the management of medical staff and auxiliary services.

3.1 A Monitoring and Regulatory Body That Favours Openness

It is already known that the mini-hospitals will not be managed by a CI(U)SSS. The government has also said that it does not plan to establish a management framework like that of the FMGs.(33) It is therefore plausible that the mini-hospitals will be run by an entity such as a management company. In this regard, the Canada Health Act does not prohibit the administration of a hospital by entrepreneurs or for-profit organizations. The Quebec government is therefore within its rights to delegate the management of these (mini-) hospitals to such independent entities. Moreover, this constitutes one of the preconditions for making sure they have the best possible chance of success.

Quebec could thus reproduce the experience of other countries where entrepreneurs run certain hospitals, like Sweden(34) and the United Kingdom. Indeed, in the UK, there are more than 140 private hospitals run by companies that provide treatment within the public system and receive public funds.(35) Normally, these hospitals are run like businesses, with a focus on generating profits for their owners and shareholders. However, they are required to provide care to NHS patients in the same manner as hospitals that are part of the public sector, and they are subject to the same inspections and regulatory standards.

In Sweden, there are six hospitals run by entrepreneurs but financed with public funds.(36) There is actually a similar kind of public-private partnership in Quebec, with the so-called “private funded” CHSLDs (long-term care centres) which are operated by independent managers and are subject to the same obligations as public CHSLDs in terms of the number and quality of services. Furthermore, assessment visits of the province’s CHSLDs show that private funded CHSLDs provide a better quality of life than facilities managed by the government.(37)

It is indispensable for quality control to be objective and independent, in the spirit of respecting the opening up of the current system to competition.

These types of partnerships take advantage of the private sector’s management resources and skills. In this manner, hospital administrators can provide substantial benefits to patients and workers, such as a reduction in wasted resources (see Section 3.3 below) and innovative ideas for improving health treatments and working conditions. After all, the main constraints related to efforts to improve the health care system are a lack of accountability, inadequate communication, and a rigid work culture, which leads to the demoralization of program execution teams.(38)

The supervision of treatment quality is an important concern, whether in the public or the private system. In Quebec, CI(U)SSSs are generally responsible for ensuring the quality of care provided to the population over a given area.(39) More specifically, the public facilities run by boards of directors have an oversight and quality control committee.(40) The CI(U)SSSs are also responsible for oversight in the context of private funded CHSLDs.

However, the SMCs operate under a different system: If they want to carry out their activities, they must be accredited by Accreditation Canada, an independent organization evaluating health organizations. It bases itself on standards established by the Health Standards Organization.(41)

Given the hybrid nature of the mini-hospitals, it would be more reasonable to subject them to assessment by Accreditation Canada, an organization that has developed an expertise in the matter and the only one currently recognized by the Department of Health and Social Services, rather than placing them under the control of a CI(U)SSS. Accreditation Canada’s approbation could, when appropriate, be combined with oversight of the professional orders that oversee their members in order to ensure that they respect their code of ethics.

In any case, it is indispensable for quality control to be objective and independent, in the spirit of respecting the opening up of the current system to competition. In this way, the risk of excessive rigidity resulting from an improper assessment of the quality of care would be reduced as much as possible.

3.2 Allowing for the Flexible Management of Medical Staff

One of the most important preconditions for ensuring the success of the mini-hospitals is for them to be able to completely rethink work organization and to be in charge of managing their medical staff. To do so, they will need to be free from the rigid structures of the public sector, notably the obligation to unionize and the imposition of collective bargaining agreements. Mini-hospital employees and employers must not be subject to the public system’s collective agreements, or at the very least, the most paralyzing provisions of these agreements must be avoided.

Not imposing the public sector’s collective agreements on the mini-hospitals would create an environment that is more conducive to efficiency and innovation.

In this regard, a study from HEC Montréal and CIRANO concluded that “collective agreements, other agreements with unions, and existing management and authorization procedures did not favour the development of an efficient, innovative environment.”(42) Thus, not imposing the public health care sector’s collective agreements on the mini-hospitals would create an environment that is more conducive to efficiency and innovation. This would apply as much for medical operations as for work organization, to the great benefit of patients. It is necessary to think outside the box in order to achieve greater efficiency in the mini-hospitals.

3.3 Allowing for the Flexible Management of Auxiliary Services

Other than controlling the management of their own staff, the administrators of the mini-hospitals should have flexibility in the management of the supply of auxiliary services, such as security, maintenance, and the procurement of food, computer software, medical equipment, etc. In other words, administrators have to be able to freely choose their procurement model, as long as they meet required quality standards. In this way, the mini-hospitals could closely monitor the rapid evolution of technology and knowledge in hospitality (restaurant services, laundry, building improvements, but also medical equipment, etc.). They could also better adapt to the constantly evolving needs of patients, and do so at lower cost.

If the mini-hospitals are subject to the same relatively rigid procurement rules as public hospitals, these benefits will never materialize. For example, public hospitals must go through the Centre d’acquisitions gouvernementales (CAG), a body that also administers calls for tender, in order to receive approval for group purchases of equipment and supplies.(43) Despite the government’s promises back in 2019,(44) the lowest bidder rule is still applied when awarding public contracts in the area of health care. Thus, factors like overall long-term value and the encouragement of innovation are not presently taken into account when it comes time to purchase medical equipment for hospitals. The administrators of the mini-hospitals should have the freedom to choose the equipment they deem most appropriate and likely to best meet their needs, whether these are the least expensive option or not.

3.4 Reducing Unnecessary Paperwork

Another way to ensure greater efficiency in the mini-hospitals is to allow their administrators full latitude to limit the paperwork that currently paralyzes health professionals.(45) One of the first aspects to restructure could be the quantity of forms doctors must fill and how many administrative tasks they must perform, which prevents them from treating more patients. These forms can include various types of requests: disability wage-loss insurance, mortgage insurance, personal loan insurance, travel insurance, life insurance, driver’s licences, etc.(46)

Doctors in Canada devote nearly 19 million hours a year to administrative activities.

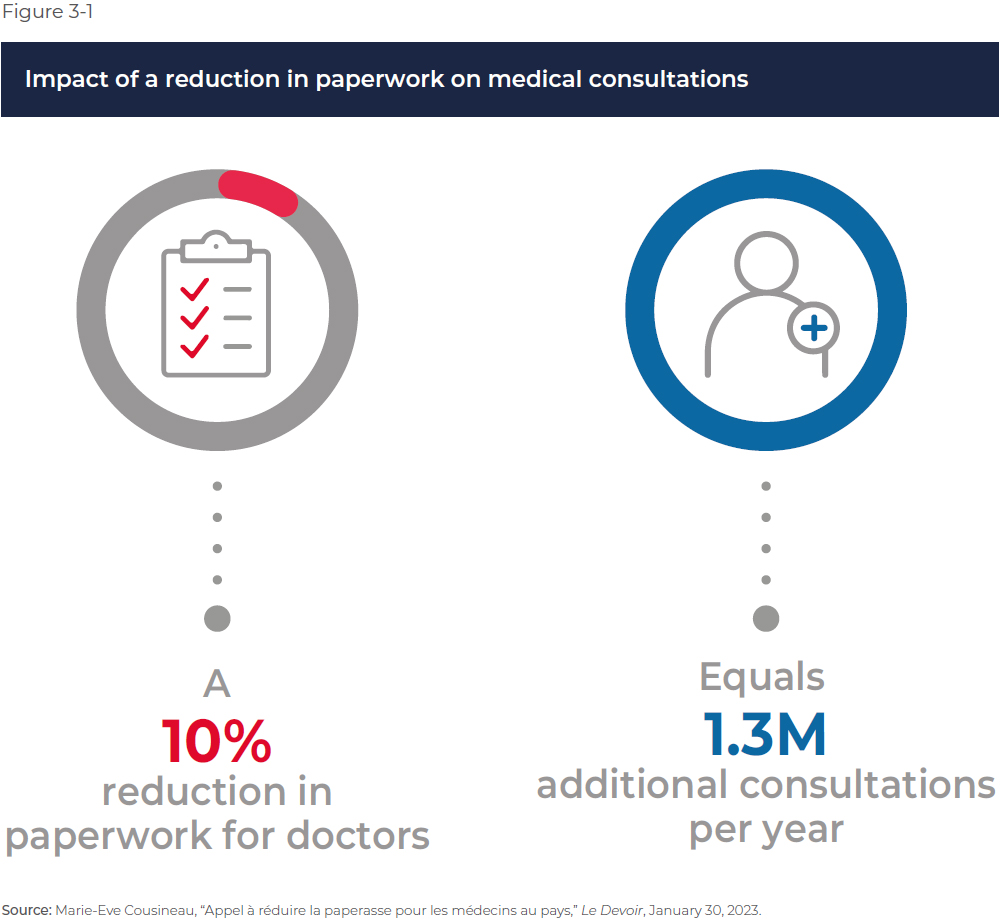

A recent Canadian Federation of Independent Business report found that doctors in Canada devote nearly 19 million hours a year to related administrative activities.(47) These lost hours represent the equivalent of over 55 million medical consultations a year. The same report estimated that if pointless paperwork were eliminated or entrusted to other professionals, over 13 million more medical consultations could be provided each year in Quebec. If even 10% of these tasks were eliminated, the working conditions of doctors would be improved and the rate of professional burnout would be reduced(48) (see Figure 3-1). Moreover, according to a study carried out in 2020 among doctors in Nova Scotia, 38% of doctors’ administrative tasks were identified as unnecessary and able to be carried out by other employees (24%) or simply eliminated (14%).

It is therefore crucial to allow entrepreneurs to innovate and find solutions to reduce paperwork in the mini-hospitals in order for doctors to take charge of the largest possible number of patients. Doctors could have up to 9.7 hours more out of every 40 hours of work to devote to consultations if they did not have to take care of unnecessary administrative tasks and paperwork, as illustrated by a 2022 poll. The Quebec government must therefore allow mini-hospitals to simplify and eliminate unnecessary forms, like Nova Scotia, which has committed to reducing the time doctors devote to useless tasks by 50,000 hours by the end of 2023.(49)

CHAPTER 4 – Remove the Most Restrictive Regulatory and Legislative Obstacles

There are some regulatory obstacles that will need to be scaled down or eliminated to give the mini-hospitals the best possible chance of success right from day one. These obstacles include:

- the prohibition on mixed practice;

- impediments to increasing the supply of health care professionals;

- the prohibition on hospitalizations of over 24 hours; and

- the regional medical staffing plan (PREM) regulations that restrict the mobility of doctors.

4.1 Lifting the Prohibition on Mixed Practice

The prohibition against doctors practising in both the public and the private systems when it comes to medical acts insured by the RAMQ is set out in Section 22 of Quebec’s Health Insurance Act.(50) In sum, it is forbidden for a doctor remunerated by public funds, commonly known as a participating doctor, to provide the same health care treatments in the private and public sectors.(51)

It must be noted, however, that mixed medical practice is not expressly prohibited by the Canada Health Act. It is Quebec that imposes such a restriction on its health professionals. The provincial government would thus be well within its rights to lift this prohibition, which would entail numerous benefits.(52)

- First of all, mixed practice is a necessary condition for mini-hospitals to be able to fully use their residual capacity (see Section 2.3), insofar as the services would then be provided to a private sector clientele. Mixed practice is therefore also a precondition for the mini-hospitals to have access to an additional source of revenue.

- Second, allowing doctors to work in both the public and private sectors has the benefit of making more efficient use of highly qualified medical personnel. Indeed, unused time due to the rationing of care in the public sector could be used to treat patients in a private context, which would increase the total volume of services provided. Moreover, working in the private sector can improve the knowledge and technical skills of doctors, which increases the overall quality of care provided, including within the public system. Similarly, professionals working in both systems would have an added incentive to perform well in the public sector in order to build up a good reputation for their work in the private sector.(53)

- Finally, by authorizing mixed practice, Quebec would join the many industrialized countries, as well as the four Canadian provinces of Manitoba, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland and Labrador, that do not prohibit it(54) (see Table 4-1).

An objection often raised against authorizing mixed practice is that it would lead to a reduction in the number of hours worked in the public system. Yet international experience shows that doctors working in countries that authorize mixed practice, like Australia(55) and Denmark,(56) do not devote less time to taking care of patients in the public system than their counterparts practising solely in the public sector. In any case, the worry about an exodus could be allayed by establishing, if needed, a minimum number of hours worked in the public system, as was done in England in 2003.(57)

Doctors working in countries that authorize mixed practice do not devote less time to taking care of patients in the public system.

Of course, such concerns emerge because the supply of doctors is limited. Other measures should be taken to increase the number of medical professionals.

4.2 Removing Obstacles to the Training and Integration of New Medical Staff

The most direct method is to increase the number of students admitted each year into the province’s different medical school programs. Not only is this number too small(58) today to possibly meet the growing needs of the population, but there is no guarantee that all students who complete their studies will practise their profession in the province, or even that all students admitted will complete their studies and become doctors.

Facilitating the recognition of the skills of professionals from other provinces and countries could also help resolve the current shortage. It is recognized that this is generally a long and difficult process. Numerous Canadians having studied abroad could come live and work in Quebec if the recognition of diplomas were simplified.(59) Along these lines, the Ontario government recently tabled a bill to allow health professionals accredited in another Canadian province to practise their profession more easily in Ontario.(60) The Quebec government should follow this example.

In addition to increasing the size of the health care workforce, the government should also take steps to maintain the personnel already trained and working. In the current context, agencies and private clinics are often a last resort for professionals who are on the verge of leaving the health care sector. Bill 15,(61) if adopted in its current form, would abolish private agencies and force nursing staff to work for Santé Québec. The elimination of this flexibility runs the risk of leading more professionals to change profession.

4.3 Lifting the Prohibition on Hospitalizations of More Than 24 Hours

The current plan for the mini-hospitals project does not include providing care requiring hospitalization. This suggests thatthe mini-hospitals will be subject to the same regulations as Specialized Medical Centres, which are not authorized to hospitalize patients for more than 24 hours.(62) Patients with simple cases are thus directed to SMCs, while moderate or complex cases are treated in hospitals.

The number of students admitted each year into the different medical school programs is too small to meet the growing needs of the population.

However, certain pilot projects are already in the works to authorize some SMCs to hospitalize patients for one night, and possibly up to 72 hours, which would allow them to carry out more complex procedures.(63) This constraint should be relaxed even more, and applied to the mini-hospitals to ensure a better distribution of cases among different facilities. It should be noted, moreover, that such a modification would not violate the Canada Health Act, which does not prohibit hospitalization of over 24 hours in health facilities like the SMCs or the future mini-hospitals. As the case may be, they will have to have the equipment and skills (health professionals qualified to carry out surgical interventions) allowing them to adequately take charge of cases requiring hospitalization of over 24 hours.

Allowing the mini-hospitals to keep their patients overnight could be a point of distinction with SMCs and favour the development of their capacities so as to diversify the types of services they offer, and thus further relieve the pressure on public hospitals.

4.4 Adjusting the Regional Medical Staffing Plans

The regional medical staffing plans (PREM) for family medicine are the administrative framework through which the government distributes new family doctors among the province’s administrative regions according to need. Each administrative region is allocated a target for the recruitment of family doctors.(64) The staffing plans for the regions where the mini-hospitals will be located will have to reflect the addition of a health care facility that will disburse a wide range of services requiring family doctors and medical specialists. Otherwise, these regions could face a shortage of medical personnel.

Allowing the mini-hospitals to keep their patients overnight could further relieve the pressure on public hospitals.

Furthermore, when new family doctors receive their notice of compliance with the PREM,(65) they agree to devote at least 55% of their billing days, on an annual basis, to the region or the subterritory indicated by this notice of compliance.(66) However, there is an exception: doctors who do not hold a notice of compliance for the Quebec City region(67) cannot practise there for more than 5% of their billing days.(68) This rule could be problematic in the case of the mini-hospital that will be located in this region, since it would reduce the volume of resources available to meet exceptional needs. It should therefore be lifted, or at the very least relaxed.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The construction of two new private mini-hospitals in the province has the potential to provide Quebecers with substantial benefits. For this potential to be realized, however, several conditions must be met in order to ensure the project’s success. These conditions can be grouped into four general statements:

- Open up the current health care system to competition, inspired by examples from Quebec and abroad.

- Ensure adequate financing through activity-based funding, a sufficient budgetary envelope, and additional sources of revenue.

- Allow for the flexible management of medical personnel and auxiliary services.

- Lift the most restrictive legislative and regulatory prohibitions.

These conditions are crucial to creating an environment conducive to innovation and efficiency in the area of health care, all while guaranteeing quality of care and equitable access for patients. If all of these conditions are met, it will increase the chances that this new project will be deployed optimally.

Each condition can be fulfilled without violating the Canada Health Act or compromising the universality of the Quebec health care system. These are achievable conditions already present in numerous industrialized countries with universal health care. Quebec therefore has the opportunity to catch up with these countries by adopting a legal and regulatory framework that respects these four conditions.

These conditions are crucial to creating an environment conducive to innovation and efficiency, all while guaranteeing quality of care and equitable access for patients.

Moreover, the benefits associated with this project are not limited to the mini-hospitals themselves; the entire hospital system could be affected and take inspiration from these new facilities. For example, if the mini-hospitals offer working conditions likely to attract medical personnel having left the public system or working elsewhere in that system, this could compel unions to review their practices in public facilities.

Similarly, removing obstacles that slow the increase of the size of the health care workforce could benefit the hospital system as a whole by increasing the capacity of the system in general, which would shrink waiting lists. The innovations introduced in the mini-hospitals could then be adopted throughout the hospital system, which would allow it to enjoy the efficiency gains achieved.

In the end, the success of this project will provide the Quebec population with more health care services and a better treatment experience with the available resources.

Annex A – Specialized Medical Centres

Specialized Medical Centres (SMCs) were created in 2006 in order to shorten wait lists for elective surgeries and increase access to certain specialized services.(69) According to the Act Respecting Health Services and Social Services, an SMC is “a place, outside a facility maintained by an institution, that is equipped for the provision by one or more physicians of medical services necessary for a hip or knee replacement, a cataract extraction and intraocular lens implantation or any other specialized medical treatment determined by regulation of the Government.”(70)

There are two types of SMC:(71)

- Those in which the practising doctors are participating (opted in to the public insurance plan), known as participating SMCs. These represent the majority of SMCs, with 50 of them as of April 2023.(72) The medically necessary services provided in these centres are covered by the RAMQ public insurance plan. Public hospitals may also enter into agreements with these SMCs to reduce wait lists, provided they obtain approval from the Minister of Health and Social Services. This agreement allows the hospital to delegate the provision of determined specialized medical services to the SMC, for a maximum duration of five years.

- The 23 other SMCs are those in which the practising doctors are non-participating, and are known as non-participating SMCs. The medical services provided in these centres are not covered by the RAMQ. Private insurance can cover the cost of a total hip or knee replacement, or a cataract extraction with intraocular lens implantation.(73) These SMCs cannot enter into agreements with public hospitals, limiting the extent to which non-participating physicians can help reduce the length of public system wait lists.

Given the prohibition of mixed practice, an SMC cannot be operated by both participating and non-participating doctors.

In recent years, the types of treatments carried out in SMCs have been diversified, to the great benefit of patients.(74) Agreements between participating SMCs and hospitals have also multiplied,(75) reaching 28 in number as of March 2021. These agreements constitute contracts according to which hospitals or CI(U)SSSs purchase operating priorities(76) in participating SMCs in order to increase the capacity of the system and reduce wait times for surgeries. In this case, public sector patients can be operated in these SMCs for no additional charge, as the costs are covered by the health and social services network (RSSS). However, to have access to the surgical services covered by the RSSS, a patient must have been on a wait list for over six months.(77) It is only at this stage that the hospital that prescribed the operation can offer the patient the option to be operated in an SMC with which it has an agreement.

Nonetheless, to reduce wait times and thus avoid long periods of disability or quickly return to a satisfying quality of life, patients can choose to be operated in a non-participating SMC at their cost, or their employers’ cost. Employers who have signed particular agreements with their insurer can propose private surgeries to their employees upon approval of the file by the insurer. Similarly, certain patients discouraged or unsatisfied with the wait time for their procedure in the public sector can choose to pay for a procedure in a private specialized medical centre. In either case, the final decision is up to the patient.

The two types of SMCs thus make substantial contributions to achieving the objective of reducing wait times set by the public authorities.

References

- Department of Health and Social Services of Quebec, Accès aux services médicaux spécialisés – Volet chirurgie, Sommaire en attente, consulted April 21, 2023.

- Emmanuelle B. Faubert, “Learning to Be Patient: Emergency Room Wait Times Keep Rising Despite Promises,” Viewpoint, MEI, March 2023.

- As of April 2023.

- Office of the Quebec Minister of Health, “Création de mini-hôpitaux privés – Québec fait un pas de plus vers la réalisation de son engagement,” press release, March 7, 2023.

- Coalition Avenir Québec, “Nouveaux centres médicaux privés au service des Québécois,” September 3, 2022.

- Hugo Pilon-Larose, “La CAQ veut construire des “mini-hôpitaux” privés d’ici 2025,” La Presse, September 4, 2022; Office of the Quebec Minister of Health, op. cit., footnote 4.

- While the government has not yet released any details about the exact nature of what constitutes a minor case in this context, according to Department of Health and Social Services definitions, it is reasonable to think that minor cases in this context consist of patients having reason to seek medical or psychosocial consultation and whose condition does not require a stretcher. Department of Health and Social Services of Quebec, Professionnels, Soins et services, Guide de gestion des urgences, Gestion clinique de l’épisode de soins, April 26, 2020.

- Official call for expressions of interest document (Document officiel des appels d’intérêt).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Hugo Pilon-Larose, op. cit., footnote 6.

- Office of the Quebec Minister of Health, op. cit., footnote 4.

- Valérie Paris, “Les comparaisons internationales des hôpitaux : apports et limites des statistiques disponibles,” Revue française d’administration publique, Vol. 2, No. 174, 2020, p. 370.

- The Commonwealth Fund, International Health Care System Profiles: France, June 5, 2020.

- Karine Chevreul et al., “France: Health system review,” Health Systems in Transition, Vol. 17, No. 3, September 15, 2015, pp. 130-131.

- According to the OECD’s definition of a hospital, Quebec has no private hospitals. OECD, “OECD Health Statistics 2022: Definitions, Sources and Methods,” July 2022.

- Patrick Bellerose, “Pour leur budget de fonctionnement, les hôpitaux publics devront faire concurrence au privé,” Le Journal de Québec, April 25, 2023.

- Francis Vailles, “Révolution dans le financement des hôpitaux,” La Presse, May 9, 2022.

- Clas Rehnberg, “The experience of the DRG-reimbursement system in the Stockholm county council,” Applied Health Economics Sweden, March 27, 2012, p. 5.

- Wilm Quentin et al., “How Denmark, England, Estonia, France, Germany, and the USA Pay for Variable, Specialized and Low Volume Care: A Cross-country Comparison of In-patient Payment Systems,” International Journal of Health Policy and Management, Vol. 11, No. 12, 2022, p. 2943; Westminster Health Forum, Payment systems and reimbursement in healthcare, 2020, cited in Matthew Bell, Anita Charlesworth, and Richard Lewis, “REAL Centre Briefing: The future of the NHS hospital payment system in England,” The Health Foundation, July 2021, p. 4; Clas Rehnberg, ibid., p. 6.

- Business Development Bank of Canada, Operating expenses (selling, general & administrative expenses), consulted May 9, 2023.

- Héloïse Archambault, “Les salles d’opération toujours sous-utilisées,” Le Journal de Montréal, January 16, 2019.

- Idem.

- Hugo Pilon-Larose, “La CAQ veut construire des ‘mini-hôpitaux’ privés d’ici 2025,” La Presse, September 4, 2022; Department of Health and Social Services of Quebec, “Programme de financement et de soutien professionnel pour les groupes de médecine de famille,” fiche explicative, February 2022.

- Marianne Casavant, “Les modalités de financement des GMF, GMF-U et GMF-R,” Le Médecin du Québec, November 28, 2017.

- To be eligible for RAMQ coverage, foreign students must hold a bursary from the Department of Education or the Department of Higher Education of Quebec, or come from a country with which Quebec has concluded a social security agreement (Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Greece, Luxembourg, Norway, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, Sweden). Régie de l’assurance maladie, Social security agreements with other countries, consulted May 9, 2023.

- This is a prudent estimate of the number of foreign students and foreign workers since the IDQ actually estimates the number of jobs held by these. Institut du Québec, Bilan 2022 de l’emploi au Québec, February 2023, p. 22.

- LégisQuébec, Health Insurance Act, section 22, 1999, consulted May 9, 2023.

- David Corner, “The United Kingdom Private Finance Initiative: The Challenge of Allocating Risk,” OECD Journal on Budgeting, Vol. 5, No. 3, 2006, p. 41.

- Ibid., pp. 41-42.

- Government of the United Kingdom, Private Finance Initiative and Private Finance 2 Projects: 2019-21 summary data (HTML), April 12,l 2023.

- Marie-Eve Cousineau, “Les cliniques privées gonflent leur marge de profit avec la pandémie,” Le Devoir, April 13, 2021.

- Addenda to the calls for information (appels à l’information).

- Maria Lily Shaw, Real Solutions for What Ails Canada’s Health Care Systems – Lessons from Sweden and the United Kingdom, Research Paper, MEI, February 2022, p. 63.

- OECD, Subnational Public-Private Partnerships: Meeting Infrastructure Challenges, 2018, p. 83.

- Maria Lily Shaw, op. cit., footnote 35, p. 63.

- Patrick Déry, “Does Entrepreneurship Make a Difference in Health Care? The Case of Private Funded CHSLDs,” MEI, Viewpoint, October 2019, p. 1.

- Mariateresa Torchia, Andrea Calabrò et Michèle Morner, “Public-Private Partnerships in the Health Care Sector: A systematic review of the literature,” Public Management Review, Vol. 17, No. 2, 2015, p. 251.

- Government of Quebec, Health, Health system and services, Service organization, CISSS and CIUSSS, April 18, 2018.

- Vos droits en santé, Organismes du système de santé, Le réseau de la santé du système de santé, la structure locale: les établissements de santé, L’organisation des établissements, Le conseil d’administration (CA), Le Comité de vigilance et de la qualité, consulted May 4, 2023.

- Accreditation Canada, About Accreditation Canada, consulted May 4, 2023; Department of Health and Social Services of Quebec, Professionnels, Permis, Obtention d’un permis de centre médical spécialisé (CMS), consulted May 4, 2023.

- Authors’ translation. Nadia Benomar, Catalyseurs et freins à l’innovation en santé au Québec, Rapport d’étape, HEC Montréal and CIRANO, July 2016, p. 47.

- Government of Quebec, Gouvernement, Appels d’offres et acquisitions, Regroupement d’achats de biens et de services, February 23, 2023.

- Éric Desrosiers, “Québec révisera la règle du plus bas soumissionnaire,” Le Devoir, October 30, 2019.

- Radio-Canada, “La montagne de paperasse des médecins nuit aux soins des patients, dénonce la FCEI,” Radio-Canada, January 30, 2023.

- Marie-Eve Cousineau, “Appel à réduire la paperasse pour les médecins au pays,” Le Devoir, January 30, 2023.

- Idem.

- Authors’ calculations. Idem.

- Idem.

- Government of Quebec, Health Insurance Act, Section 22, consulted March 15, 2023.

- Any doctor wishing to practise in the private sector and provide patients with treatments covered by the RAMQ must first formally withdraw from the public system by sending the corresponding form by mail, and then wait 30 days before practising in the private sector.

- Maria Lily Shaw, Real Solutions for What Ails Canada’s Health Care Systems – Lessons from Sweden and the United Kingdom, Research Paper, MEI, February 2022, p. 53.

- Ibid., p. 53.

- Ibid., p. 45.

- Terence Chai Cheng, Catherine M. Joyce, and Anthony Scott, “An Empirical Analysis of Public and Private Medical Practice in Australia,” Health Policy, Vol. 111, No. 1, 2013, p. 48.

- Karolina Socha and Mickael Bech, “Dual practitioners are as engaged in their primary job as their senior colleagues,” Danish Medical Journal, Vol. 59, No. 2, 2012, p. 5.

- Maria Lily Shaw, op. cit., footnote 53, p. 44.

- The three-year policy for admissions projects 969 of them in 2022-2023, climbing to 1,003 in 2023-2024 and to 1,021 in 2024-2025. Office of the Health Minister of Quebec, “Planification des admissions au doctorat en médecine – 969 admissions aux programmes de formation doctorale en médecine pour la prochaine année,” press release, June 10, 2022.

- Francis Beaudry, “Les médecins canadiens formés à l’étranger, une solution à la pénurie?” Radio-Canada, May 18, 2022.

- Government of Ontario, “New ‘As of Right’ Rules a First in Canada to Attract More Health Care Workers to Ontario,” press release, January 19, 2023.

- Government of Quebec, An Act to make the health and social services system more effective, March 29, 2023, p. 6.

- Nadia Benomar and Marie-Hélène Jobin, Portrait des tendances et des pratiques de la chirurgie ambulatoire, Pôle santé HEC Montréal, June 2021, p. 23.

- Daniel Boily and David Gentile, “Des cliniques chirurgicales privées vont pouvoir hospitaliser des patients,” Radio-Canada, May 13, 2023.

- A similar mechanism also exists for specialists.

- This is the equivalent of a right to practise in the region.

- Doctors can therefore devote up to 45% of their billing days to practising outside the region where they hold their notice of compliance. Department of Health and Social Services of Quebec, Guide de gestion des plans régionaux d’effectifs médicaux en médecine de famille 2022-2023, January 12, 2023, p. 4.

- Except for the sub-territories located in Portneuf and Charlevoix.

- Department of Health and Social Services of Quebec, op. cit., footnote 67, p. 5.

- Sylvie Bourdeau, “Canada: After ‘Chaoulli’… Bill 33 opens the door to private clinics and private insurance in Quebec,” Mondaq, July 28, 2006.

- LégisQuébec, Act Respecting Health Services and Social Services, 1991, Section 333.1.

- Maria Lily Shaw, Real Solutions for What Ails Canada’s Health Care Systems – Lessons from Sweden and the United Kingdom, Research Paper, MEI, February 2022, p. 48.

- Department of Health and Social Services of Quebec, Liste des centres médicaux spécialisés ayant reçu un permis en date du 3 avril 2023.

- The possibility of purchasing private health insurance stems from the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision in the Chaoulli case, which found the prohibition on this type of insurance unconstitutional. Maria Lily Shaw, op. cit., footnote 71, p. 47.

- Nadia Benomar and Marie-Hélène Jobin, Portrait des tendances et des pratiques de la chirurgie ambulatoire, Pôle santé HEC Montréal, June 2021, pp. 14-15.

- Ibid., p. 11.

- When a CI(U)SSS concludes an agreement with a participating SMC, the latter puts at the disposal of doctors from public hospitals material and human resources in order for them to be able to perform surgeries. In other words, the CI(U)SSS pays a predetermined amount to the SMC to cover the cost of using the facilities and of labour.

- Index Santé, Chroniques santé, Thématique et références santé, Attente pour une chirurgie au Québec : questions les plus fréquentes, consulted April 21, 2023.