The Nurse Shortage in Quebec: Improving Flexibility and Working Conditions

Economic Note examining why so many nurses are leaving the profession, especially at the beginning of their careers, and how to address the problem

Quebec needs to improve flexibility and working conditions to keep young nurses in the profession, according to this study published by the MEI. “For every 100 nurses we train, 44 will leave the profession before their 35th birthday,” explains Emmanuelle B. Faubert, economist at the MEI and author of the publication.

Related Content

Related Content

This Economic Note was prepared by Emmanuelle B. Faubert, Economist at the MEI. The MEI’s Health Policy Series aims to examine the extent to which freedom of choice and entrepreneurship lead to improvements in the quality and efficiency of health care services for all patients.

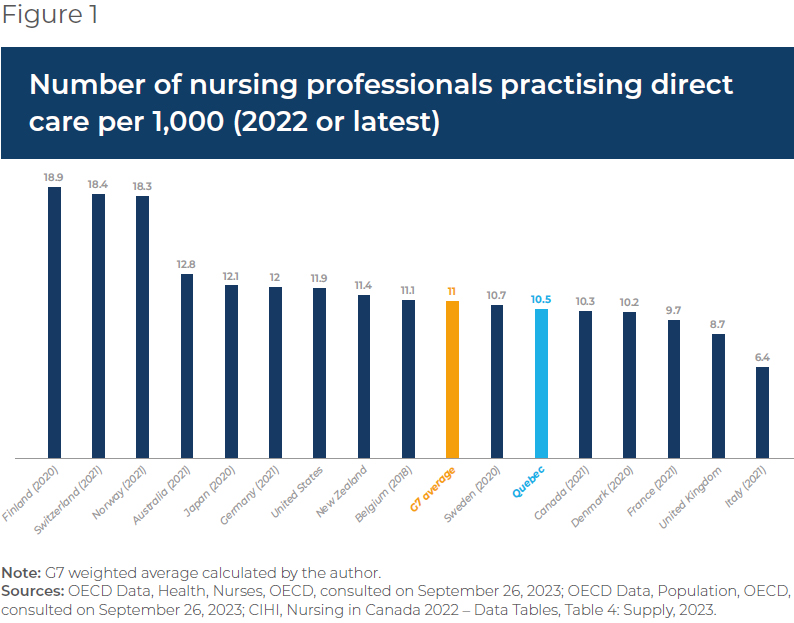

In 2021, Quebec’s Health Minister said that the province was short 4,000 nurses.(1) That same year, 6,524 nurses left the profession. Out of the 105,692 nurses registered that year, this is quite a lot.(2) While the number of nurses in Quebec per 1,000 population is similar to the Canadian average, it is somewhat lower than the G7 mean (see Figure 1).(3) Importantly, our ranking may considerably worsen as the minister expects the shortage of nurses to grow to 28,000 by 2026, due in part to how many are leaving the profession.

Why are so many nurses leaving? While baby boomers leaving for retirement can explain a portion of the increased departures, it certainly doesn’t explain all of them. A variety of difficult working conditions—unpleasant work environments, heavy workloads, emotional strain—lead nurses to quit, especially at the beginning of their careers.(4) Unfortunately, recent changes by the Quebec government will only exacerbate the problem.

How Many Nurses Are Leaving?

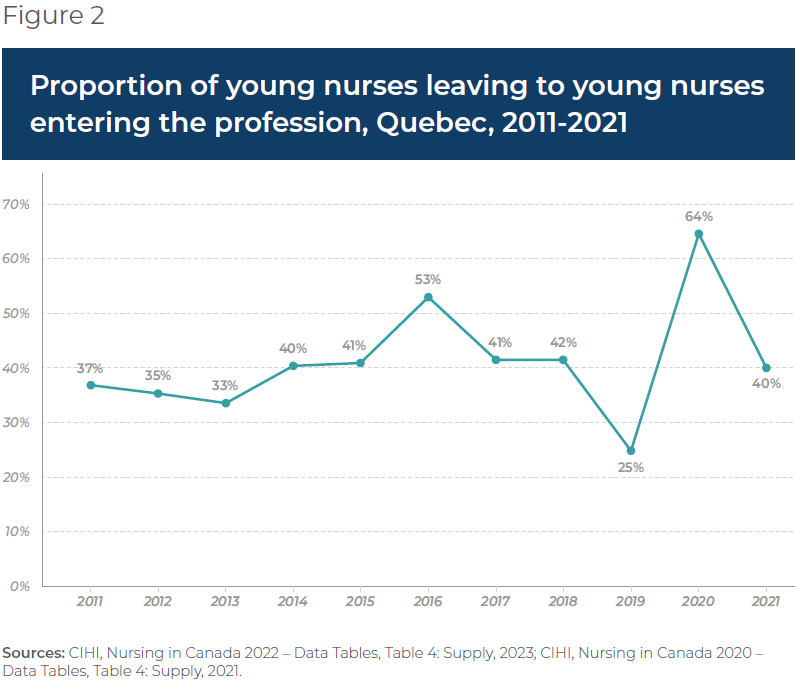

The proportion of young nurses leaving the profession has been gradually increasing of late. In 2011, with nearly 5,000 new nurses under 35 entering the system, 1,800 left, or just under 37%. Ten years later, that proportion had risen to nearly 40% (see Figure 2), with a few abrupt swings up and down. While 2019 unexpectedly saw a lot of new young nurses and fewer departures, 2020 had the fewest new young nurses in the 11-year period examined, while simultaneously having the most departures.

Taking the average between 2011 and 2015, we find that for every 100 new young nurses that entered the profession in the province, 37 left. When looking at the period from 2016 to 2021, that proportion grows to 44 out of 100,(5) an 18% increase.

While nurses who had graduated less than 10 years before made up 42.8% of the total nursing supply in 2012, that proportion had fallen to 38.5% in 2022.(6) As these young nurses make up a large proportion of the supply of nurses and are essential to ensuring the long-term future of the system, it is crucial to keep as many of them as possible in the profession.

Why Do Nurses Choose to Leave Their Profession?

We are in a situation where there is a shortage of certain professionals, and while many such professionals enter the field, a lot of them soon quit. Normally, the labour market would respond by increasing wages, benefits, and conditions for professions in high demand in order to maintain, or even increase, the supply of qualified professionals.

In 2020-2021, the median hourly wage for registered nurses in Quebec was $37/hr, or $72,150 annually.(7) As for licensed practical nurses, the median hourly wage in the Montreal area, for instance, was $26/hr, or $50,700 a year.(8) According to a survey conducted in June 2023, 42% of nurses polled were considering leaving the profession. Of these, 71% mentioned overwork being the main cause, with 58% declaring the pay to be insufficient.(9)

Quebec’s Health Minister expects the shortage of nurses to grow to 28,000 by 2026.

Such data show that while wages are an issue, they are not the only or even the main source of the problem. It is the lack of other types of incentives, in addition to the insufficient remuneration, that leads to a persistent shortage of nurses. For example, at the Maisonneuve-Rosemont hospital, over a hundred ER nurses signed a petition in January 2023 demanding concrete changes regarding their working conditions and the overuse of mandatory overtime, as well as the resignation of their team leader, without which they would all resign before the end of the month.(10)

The poor state of working conditions for nurses has been known for years,(11) and despite this, many young people still choose to study nursing. Yet for a variety of reasons, many also leave soon after starting.

Due to collective agreements and an overreliance on seniority, younger nurses are heavily disadvantaged compared to their older colleagues. Shift allocation and schedules rarely work in their favour,(12) with mandatory overtime and relatively more stressful working conditions overall for young nurses. Such disparity of treatment can cause tension among staff, leading to professional exhaustion.(13) Also, centralized decision-making does not cater to the specific needs of different regions, whether for patients or nursing staff.

But if nurses already lack flexibility due to centralized decisions, the situation will only get worse with Bill 15.(14) Proposed in March 2023, this bill(15) is another step in centralizing decisions even more by creating the Santé Québec agency, destined to become the sole health care employer in the province. In combination with Bill 10,(16) also tabled earlier in 2023, it aims to eliminate the systematic use of employment agencies in health care and bring workers more under the authority of the government.

Currently, nurses in the province still have some employment options. They can work for the public sector or the private sector. When they don’t want to work directly for the government, many go through employment agencies in order to find the employment that suits them best. For nurses working in government-run hospitals on the verge of quitting, these employment agencies can be the last thing keeping them in the profession.

42% of nurses polled were considering leaving the profession. Of these, 71% mentioned overwork being the main cause.

The passage of Bill 10, and Bill 15 if it is also passed, will eliminate these safety valves for these nurses, leaving them with only two options: either working for the government, or no longer practising in Quebec at all. It would also put at risk the functioning of private health care establishments such as independent clinics or the future mini-hospitals, which would struggle to find nurses.

Incidentally, a recent report showcased similar problems in Ontario, where many nurses have left the system to work in the United States,(17) often while still living in Ontario. Some of the most common reasons stated were related not only to better compensation, but more importantly, to better schedules and working conditions.

Fixing the Problem

Ideally, Quebec must improve working conditions in the public sector to encourage nurses to stay in the profession. They need more flexibility in terms of schedules and shift attributions. For example, weekend and night shifts should be distributed on a rotation basis rather than leaving all the less desirable shifts to newer and younger nurses. The fact that these improvements have not been implemented yet within the public sector, though, suggests that doing so will be difficult.

There is another option: to maintain, and indeed improve, working opportunities outside the public sector. Public health authorities need to increase employment flexibility by allowing nurses to practise their profession in the environment that suits them best, which would have the salutary side effect of putting more pressure on the public system to get its act together.

Employment agencies are crucial to maintaining that flexibility.(18) Nurses need more freedom of practice, and those agencies that help provide it should not be handicapped by regulatory obstacles, or prohibited by law.

Nurses need more freedom of practice, and those agencies that help provide it should not be handicapped by regulatory obstacles, or prohibited by law.

Mixed practice is another way to alleviate current shortages. Also known as dual practice, this refers to health care professionals working in both the private and public sectors, whether to practise their profession both in a hospital and an independent clinic, or to utilize not-for-profit hospital facilities to provide independent services.(19) One of the benefits of dual practice is precisely that it allows health care workers to remain in the public system while being able to practise outside it. Mixed practice is very common and is found in most countries around the world.(20) The case of Canada, where it is prohibited for doctors, is highly unusual.

Thankfully, nurses are not currently subject to a formal mixed practice ban, providing a safety valve for them in a situation where the public sector is the main employer. Mixed practice, even when limited in scope, allows nurses to supplement their income and to be more in control of their schedules without having to leave the public sector entirely. For example, a nurse could maintain a regular job at a hospital or Family Medicine Group while working in an independent super nurse clinic part-time through an employment agency.(21) Bill 10 and Bill 15, by limiting the use of such agencies and making the government the sole employer, would close this safety valve, causing even more nurses to stop practising in Quebec.

Nurses are the backbone of our health care system. If their working conditions make them want to quit, we cannot expect even the ones who stay to provide the best possible care to patients.(22) Instead of eliminating employment agencies and opportunities for mixed practice, and reinforcing the monopolistic position of the public sector by making it the sole employer, the government should on the contrary embrace competition from independent employers who show the way forward by providing nurses with a better working environment.

References

- Marie-Ève Morasse, “Pénurie d’infirmières dans le réseau: Une question de formation ou de rétention?” La Presse, September 9, 2021.

- The term “nurse” used in this Economic Note includes nurse practitioners, registered nurses, and licensed practical nurses in order to provide a more complete picture of the nursing supply as a whole. While nurse practitioners and registered nurses must be registered with the Ordre des infirmières et infirmiers du Québec (OIIQ), licensed practical nurses have to be registered with the Ordre des infirmières et infirmiers auxiliaires du Québec (OIIAQ). CIHI, Nursing in Canada 2022 – Data Tables, Table 4: Supply, 2023.

- OECD Data, Health, Nurses, OECD, consulted on September 26, 2023; OECD Data, Population, OECD, consulted on September 26, 2023; CIHI, Nursing in Canada 2022 – Data Tables, Table 4: Supply, 2023.

- Amanda Bucceri Androus, “The (Not So) Great Escape: Why New Nurses Are Leaving the Profession,” RegisteredNursing.org, March 10, 2023; Quebec Department of Health and Social Services, Rapport du groupe de travail national sur les effectifs infirmiers, May 2022, pp. 16-21.

- Whether it is to work as a nurse elsewhere or to change career altogether is unknown. We can, however, most likely exclude nurses leaving to start a family as this data is about the number of nurses that have a licence to practise in Quebec, regardless of employment status. This distinction is important considering the estimated average age of first-time mothers in Quebec of 29.7 years. CIHI, Nursing in Canada, 2022 – Data Tables, Table 4: Supply, 2023; Institut de la statistique du Québec, Naissances et fécondité, May 24, 2023.

- CIHI, Nursing in Canada, 2021 – Data Tables, Table 4a: Supply, 2022; CIHI, Nursing in Canada, 2022 – Data Tables, Table 4: Supply, 2023.

- Based on a 37.5-hour week. Government of Canada, Job Bank, Labour market information, Registered Nurse (R.N.) in Québec, consulted on September 18, 2023.

- Government of Canada, Job Bank, Labour market information, Licensed Practical Nurse (L.P.N.) near Montréal (QC), September 19, 2023.

- Almost 10,000 nurses took part in the survey. Fédération interprofessionnelle de la santé du Québec, “Sondage : Soins non faits,” June 2023.

- Fanny Lévesque and Henri Ouellette-Vézina, “Une centaine d’infirmières menacent de démissionner,” La Presse, January 14, 2023.

- La Presse canadienne, “Les conditions de travail des infirmières font-elles fuir les étudiantes,” Radio-Canada, March 11, 2018; Quebec Department of Health and Social, op. cit., endnote 4.

- Yvon Boudreau, “Quand l’ancienneté empoisonne la vie des jeunes infirmières,” La Presse, March 3, 2023.

- Michael Sandler, “Why are new graduate nurses leaving the profession in their first year of practice and how does this impact on ED nurse staffing? A rapid review of current literature and recommended reading,” Canadian Journal of Emergency Nursing, Vol. 41, No. 1, Spring 2018, p. 23; Denis Chênevert, “L’épuisement des professionnels de la santé au Québec,” Gestion, Vol. 43, No. 3, 2018, pp. 74-75.

- MEI, “Bill 15: Quebec is centralizing again,” March 29, 2023.

- National Assembly of Quebec, Bill 15, An Act to make the health and social services system more effective, consulted on September 27, 2023.

- National Assembly of Quebec, Bill 10, An Act limiting the use of personnel placement agencies’ services and independent labour in the health and social services sector, April 20, 2023.

- Colin Craig, “Nearly 2,000 Ontario Nurses Working in Michigan,” Policy Brief, Second Street, April 2023, p. 1.

- Michel Tremblay et al., “ Influence of Working Conditions on Satisfaction and Loyalty of Quebec Agency Nurses,” Industrial Relations, Vol. 67, No. 3, 2012, p. 496.

- Kerry Waddell et al., “Rapid evidence profile #49: Impacts of dual private/public practice by healthcare professionals on equity-centred quadruple aim metrics,” McMaster University Health Forum, May 18, 2023, p. 1.

- Javad Moghri et al., “Physician Dual Practice: A Descriptive Mapping Review of Literature”, Iranian Journal of Public Health, Vol. 45, No. 3, March 2016, p. 278.

- Giuliano Russo et al., “Understanding nurses’ dual practice: a scoping review of what we know and what we still need to ask on nurses holding multiple jobs,” Human Resources for Health, Vol. 16, No. 14, February 22 2018, p. 4; Placement Premier soin, Santé: travailler dans le public ou le privé?, consulted on September 26, 2023.

- This survey shows that this is already a major problem, with some elements of care often rushed and sometimes skipped altogether. Fédération interprofessionnelle de la santé au Québec, Faits saillants du sondage sur les soins non faits, 2018.