Second Time’s the Harm: Repeated Lockdowns Risk Turning a Temporary Downturn into an Ongoing Depression

Economic Note showing how recurring lockdowns, even if partial, risk causing permanent harm in particular to small businesses

The Quebec government has announced stricter lockdown rules before the holidays. Yet repeated lockdowns, even if partial, are likely to inflict the effects of an economic depression on SMEs rather than those of a simple recession. This Economic Note prepared by Peter St. Onge in collaboration with Maria Lily Shaw paints a worrisome picture.

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| Second time’s the harm when it comes to lockdowns (Troy Media, December 16, 2020) |

This Economic Note was prepared by Peter St. Onge, Senior Fellow at the MEI, in collaboration with Maria Lily Shaw, Economist at the MEI. The MEI’s Regulation Series aims to examine the often unintended consequences for individuals and businesses of various laws and rules, in contrast with their stated goals.

The Quebec government has announced stricter lockdown rules before the holidays. Yet repeated lockdowns, even when partial, may be converting a temporary crisis akin to a natural disaster into an ongoing depression for the small and medium-sized businesses that employ nearly 90% of Canadians who work in the private sector.(1) Research on actual natural disasters and on temporary tax changes suggest that the simple act of extending the duration or frequency of a threat can dramatically magnify its impact, potentially ballooning to many times higher in the long run.

On October 26, Quebec extended its new “partial” lockdowns another four weeks,(2) as the original “next few weeks”(3) of restrictions now stretch into eight months and counting. Unfortunately, the carnage for small business, and for the jobs they sustain, is anything but partial.

The Damage So Far

The first COVID-19 lockdowns have already been economically devastating to Canadians, leading to unemployment peaking at 13.7%,(4) the highest level since the Great Depression. What’s more, economic analysis suggests that continuing or repeat lockdowns, even if milder, could paradoxically cause greater harm. This is because a one-time lockdown destroys wealth, to be sure, but leaves economic incentives largely intact. In contrast, recurring lockdowns, even if partial, risk causing permanent harm in particular to small businesses which now must take into account an ongoing risk of catastrophe. As discussed below, a wide economic literature on natural disasters and tax changes suggests that permanence alone can dramatically increase the destruction, even if ongoing lockdowns are only partial.

Even before these current partial lockdowns were extended, small business in Canada was already on a knife’s edge. Dan Kelly, president of the Canadian Federation of Independent Business (CFIB), recently released a survey that found that eight in ten small businesses in Canada are specifically concerned about the second wave of lockdowns, with 56% saying they might not survive it.(5) Kelly told of receiving 60,000 calls from worried small business owners, many even considering suicide as their small businesses collapse.(6)

An estimated nine in ten small businesses have experienced catastrophic falls in revenue averaging 70%, and employee numbers have been cut in half, with one in ten businesses laying off their entire staff. Kelly underlined that even for surviving businesses, the vast majority were losing money every day while hoping for a quick reopening, but that a second wave will “burst that bubble.”

Meanwhile, Canadians more broadly are becoming more pessimistic(7) about the economy as lockdowns drag on with little end in sight. After rebounding somewhat, the Bloomberg Nanos Canadian Confidence Index, measuring financial health and economic expectations, has been declining week by week to levels not seen since August.(8) Faced with the prospect of a repeat lockdown, which Quebec indeed imposed days later, Goldy Hyder, president of the Business Council of Canada, predicted it would be “catastrophic.”(9)

And not just jobs and businesses are at risk, but the very character of Canada’s cities. In a recent study, the Ontario Chamber of Commerce found layoffs overwhelmingly concentrated in food services and accommodation, entertainment and recreation, and retail, which collectively make up the fabric of a city.(10) Even before the pandemic, there were deep concerns about the decline of commercial areas like the Rue St-Denis corridor in Montreal(11) as a result of aggressive and discriminatory tax and regulatory burdens, so ongoing lockdowns risk completely decimating these already struggling businesses. The longer lockdowns continue, the greater the risk of waking up to a Montreal or Quebec City or Toronto that feels like a “ghost town” for many years, with fewer restaurants, fewer arts, and fewer retail stores.

Radio-Canada recently reported that such a slow motion collapse is already underway in beloved Vieux Quebec, as small businesses are being wiped out. Already, 22 have thrown in the towel(12) and many more are likely to come. Days later, Montreal’s Time Out doubled its tally of iconic Montreal restaurants closed forever.(13) Experts, meanwhile, warn of a coming tidal wave of bankruptcy, both personal and small business, as courts that have slowed down for COVID-19 finally work through the backlog.(14)

The Danger of Extended Lockdowns

The way to stop this is simple: Stop locking down small business. There is a substantial economic literature showing that permanent changes have far larger impacts than temporary changes. These decades of research are built on Nobel laureate Milton Friedman’s “permanent-income theory,”(15) and Nobel laureate Franco Modigliani’s life-cycle theory,(16) both elaborated in the 1950s. This framework predicts that temporary changes are “smoothed” over a longer horizon, even an entire lifetime, and so have a relatively small impact, while permanent changes have a much larger impact.(17)

Over the ensuing 70 years, this framework has been applied to a number of economic phenomena, from savings and consumption to natural disasters and taxes. For example, a 2009 paper concludes that moderate natural disasters can actually promote long-term growth, with floods in particular helping, earthquakes having a mixed effect, and storms temporarily boosting GDP, presumably from repairs.(18) An earlier paper found that natural disasters promote long-term growth by forcing an update of the capital stock,(19) while a 2018 paper found positive effects when durable goods are destroyed (cars, furniture, etc.) but negative effects when productive capital like businesses or factories are destroyed.(20) Overall, the research finds that natural disasters of short duration have a surprisingly small effect on economic output.

Of course, this doesn’t mean natural disasters are a good thing, because even wrecked cars and homes imply destroying wealth, a point lucidly made two centuries ago by Frédéric Bastiat and today known as the “Broken Windows fallacy.”(21) Still, the impact of a one-time event is surprisingly mild according to the economic literature.

A second large literature exists on the economic effects of tax changes or government payments. In sum, temporary changes have little impact on behaviour, other than impacting savings, while permanent changes cause a much larger modification in behaviour because of their effect on incentives.(22)

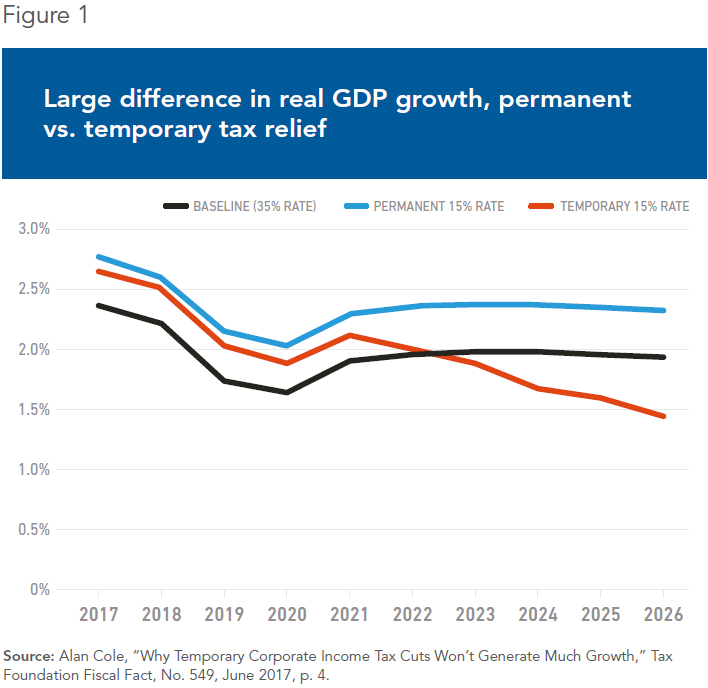

For example, one study finds that a permanent reduction in the corporate tax rate yields a 39% higher growth effect after one year than a temporary reduction, yet the difference balloons to 26-fold over a ten-year period, as the temporary reduction actually begins to have a negative effect compared to the baseline scenario after a few years (see Figure 1). Temporary reductions fail to achieve the long-term changes in behaviour that permanent tax reductions achieve.(23)

Similarly, temporary stimulus payments, often sold as a way of boosting spending during recessions or crises, widely fail to change spending behaviour, instead passing through to raise savings. In the 2001 recession, just 22% of federal stimulus payments in the US were spent,(24) while this year, just 27% of US COVID-19 federal stimulus payments were spent.(25) In terms of GDP, another paper found that a temporary stimulus boost of 3% of annual GDP over a year reduces unemployment by just 1%, implying that most of the stimulus did not change behaviour, but was simply saved.(26)

While savings are necessary for growing the economy in the long term, these results combine with the natural disaster literature to suggest that temporary changes have a far smaller impact on behaviour than permanent changes.

In the context of COVID-19 lockdowns, this suggests that repeated lockdowns, even when milder than the original, risk transforming a temporary disaster into a much larger catastrophe. The threat of repeat lockdowns forces small businesses to shoulder permanent mitigation costs, but also to account for ongoing catastrophic risk that could dissuade many from opening at all.

In evaluating this harm, it is important to remember that we have not begun to see the true economic fallout from the first lockdowns. This is partly because bankruptcy courts themselves have been all but closed down during COVID-19, and partly due to relief payments that staved off bankruptcy but are not fiscally sustainable.(27) Bankruptcy experts have warned of a “dramatic rise in defaults and consumer insolvencies” as the CERB and other relief measures end.(28) Without knowing the full extent of these costs, repeat lockdowns are the equivalent of taking out a second mortgage without even knowing how much we still owe on the first.

The Dubious Benefits of Lockdowns

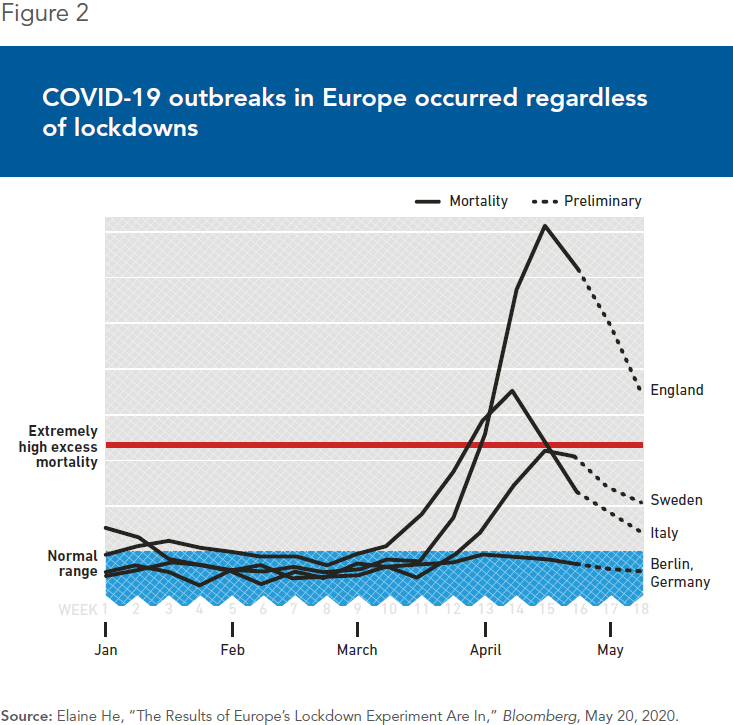

This is doubly reckless given the paucity of data on whether lockdowns carry any benefit at all. Even the World Health Organization long recommended against the kinds of measures we’ve taken as not worth the enormous cost.(29) Indeed, there is mounting evidence now that COVID-19 lockdowns have neither reduced critical cases nor reduced deaths significantly among US states or among European countries (see Figure 2), simply because most social distancing was voluntary.(30) Even worse, lockdowns targeted working age people who tend to be young and at much lower risk from COVID-19 in the first place.

In fact, a growing literature now estimates that lockdowns may actually kill more people than they save, via well-known “diseases of despair” from mass unemployment and bankruptcy, ranging from suicide to domestic abuse to fatal drug overdose.(31) We have long known that mass unemployment and poverty kill, and we should not lose sight of this when it comes to dealing with COVID-19.

Because Canadians have never before imposed lockdowns on this scale, we do not yet know how bad they will get, and we do not yet know how large that “permanence multiplier” will be. We can say with confidence, however, based on the 70-year empirical literature and on well-established economic theory, that repeated lockdowns, even mild ones, are likely to be increasingly destructive each time for the small businesses making tough choices in the face of an increasingly permanent catastrophe.

For all of these reasons, we should put a definitive end to generalized lockdowns, and focus our efforts on protecting vulnerable populations and protecting vulnerable businesses, both from the pandemic itself and from costly and counterproductive policies.

References

- Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, Key Small Business Statistics, Government of Canada, November 2019, p. 13.

- Adam Kovac, “Quebec’s red-zone restrictions extended another 28 days: Legault,” CTV News, October 26, 2020.

- The Canadian Press, “Officials say efforts by Canadians to flatten the curve of COVID-19 are working,” CTV News, May 2, 2020.

- David MacDonald, “Canada’s job losses reach Great Depression levels. Here’s how we move forward,” Behind the Numbers, June 5, 2020.

- Hilary Punchard, “56% of small businesses won’t easily survive a second COVID lockdown: Survey,” BNN Bloomberg, October 8, 2020.

- Liz Braun, “Another COVID lockdown will crush small businesses: Survey,” Toronto Sun, October 9, 2020.

- Shelly Hagan, “Canada becomes a country of pessimists with economic gloom deepening on rising virus cases,” Financial Post, October 26, 2020.

- Shelly Hagan, “Canadians are feeling worse every week about the state of the economy,” Financial Post, October 19, 2020.

- Larysa Harapyn, “A second lockdown would be catastrophic for Canadian businesses,” Financial Post, September 29, 2020.

- Ontario Chamber of Commerce, “Grim view on economy, but businesses cautiously optimistic about their outlook, survey reveals,” October 8, 2020.

- Ville de Montréal, “Le Plateau-Mont-Royal dévoile un plan d’action complet de relance de la rue Saint-Denis, une première à Montréal,” August 19, 2019.

- Jonathan Lavoie, “22 commerces fermés dans un Vieux-Québec ébranlé par la pandémie,” Radio-Canada, October 15, 2020.

- JP Karwacki, “31 notable Montreal restaurants and bars that have permanently closed,” Time Out, October 19, 2020.

- Pete Evans, “Personal bankruptcies fell to record low in April, but could be poised to soar,” CBC News, June 4, 2020.

- Milton Friedman, Theory of the Consumption Function, Princeton University Press, 1957.

- Franco Modigliani, The Collected Papers of Franco Modigliani, Volume 6, The MIT Press, July 2005.

- John B. Taylor, “Why Permanent Tax Cuts Are the Best Stimulus,” The Wall Street Journal, November 25, 2008.

- Thomas Fomby, Yuki Ikeda, and Norman Loayza, “The Growth Aftermath of Natural Disasters,” Journal of Applied Econometrics, Vol. 28, October 28, 2011, pp. 422-430.

- Mark Skidmore and Hideki Toya, “Do natural disasters promote long-run growth?” Economic Inquiry, Vol. 40, No. 4, 2002, p. 676.

- Holger Strulik and Timo Trimborn, Natural Disasters and Macroeconomic Performance, Environmental and Resource Economics, Vol. 72, No. 4, March 7, 2018, p. 1093.

- Claude Frédéric Bastiat, “The Broken Window,” Mises Daily Articles, 2009.

- Charles Steindel, “The Effect of Tax Changes on Consumer Spending,” Current Issues in Economics and Finance, Vol. 7, No. 11, December 2001, p. 5.

- Author`s calculations. Alan Cole, “Why Temporary Corporate Income Tax Cuts Won’t Generate Much Growth,” Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact, No. 549, June 2017, p. 4.

- Matthew Shapiro and Joel Slemrod, “Consumer response to tax rebates,” National Bureau of Economic Research, December 2001, p. 15.

- Olivier Coibion, Yuriy Gorodnichenko, and Michael Weber, “How Did U.S. Consumers Use Their Stimulus Payments?” National Bureau of Economic Research, August 2020, p. 11.

- Laurence S. Seidman and Kenneth A. Lewis, “A Temporary Tax Rebate in a Recession: Is It Effective and Safe?” Business Economics, Vol. 41, No. 3, July 2006, p. 37.

- Pete Evans, op. cit., footnote 14.

- Idem.

- World Health Organization, Global Influenza Programme, Non-pharmaceutical public health measures for mitigating the risk and impact of epidemic and pandemic influenza, 2019, p. 3.

- Rabail Chaudhry et al., “A country level analysis measuring the impact of government actions, country preparedness and socioeconomic factors on COVID-19 mortality and related health outcomes,” EClinicalMedicine, Vol. 25, August 1st, 2020, p. 5; Sumedha Gupta, Kosali Simon, and Coady Wing, “Mandated and voluntary social distancing during the COVID-19 epidemic,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, June 25, 2020.

- Dominik A. Moser et al., “Years of life lost due to the psychosocial consequences of COVID19 mitigation strategies based on Swiss data,” European Psychiatry, May 2020, p. 13; Frederik Feys, Sam Brokken, and Steven De Peuter, Risk-benefit and cost-utility analysis for COVID-19 lockdown in Belgium: the impact on mental health and wellbeing, PsyArXiv, May 22, 2020, pp. 3-12.