Quebec Forests: Rural Regions Lose Hundreds of Millions of Dollars a Year

Economic Note showing that it is entirely possible to increase the forest harvest all while protecting the environment, to the great benefit of rural regions and of all Quebecers

With the Quebec government about to review the province’s forest regime, environmentalists are busy trying to reduce the development of this natural resource. This publication shows, however, that we could increase the harvest of our forests without undermining the renewal of the resource.

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| Shortfall in Quebec’s forest harvest is costly to all (Montreal Gazette, October 29, 2020)

L’argent pousse dans nos arbres, récoltons-le! (Le Quotidien, October 29, 2020) Le Québec sous-exploite ses forêts publiques, selon l’Institut économique de Montréal (Le Droit, October 29, 2020) Voir l’arbre plutôt que la forêt (Le Quotidien, October 30, 2020) |

Interview (in French) with Miguel Ouellette (Midi pile, KYK Radio, October 29, 2020) |

This Economic Note was prepared by Miguel Ouellette, Director of Operations and Economist at the MEI. The MEI’s Environment Series aims to explore the economic aspects of policies designed to protect the natural world in order to encourage the most cost-effective responses to our environmental challenges.

For many years, the forestry industry in Quebec has been targeted by attacks and misinformation from certain political groups and militant NGOs who mistakenly accuse it of aggressive deforestation of the province. Quebec’s forestry sector is currently also facing additional challenges due to COVID-19 and to American protectionist measures.

At the same time, millions of dollars are lost each year due to volumes of wood unharvested from public forests. Yet more than ever, the economic recovery of our rural regions depends on the forestry sector. It is entirely possible to increase the forest harvest all while protecting the environment, to the great benefit of rural regions and of all Quebecers. This publication outlines the factors leading to this under-harvesting of Quebec forests, and provides solutions for maximizing their economic potential.

Debunking the Deforestation Myth

The forestry industry employs over 60,000 workers in Quebec, the vast majority of whom live in rural regions.(1) These high-quality jobs come with relatively high salaries. For instance, forest management workers earn $68,000 a year on average,(2) compared to the province’s average income of $43,900.

In addition to benefiting many Quebec families, the province’s forestry sector generates 2.5% of GDP and $11.9 billion in exports.(3) Moreover, contrary to what certain groups maintain, this sector is not solely made up of large companies. In fact, 72% are small businesses, and around 90% are located outside of Montreal and Quebec.(4)

A thorough analysis of the industry and its practices paints a picture that is starkly opposed to the one presented by activists. Each year, less than 1% of Quebec’s forests are harvested.(5) Furthermore, the forests regenerate themselves faster than we harvest them each year.

Every five years, the government establishes the allowable cut in Quebec. This represents the maximum volume of wood that can be harvested annually in perpetuity without diminishing the productive capacity of the forests. In other words, it is the “interest” that the forests pay out each year as they regenerate themselves.

For example, if you invest $100 at an annual interest rate of 5%, you will have $105 at the end of the year. If you spend this $5 of interest, you will still have the initial $100 of capital in your account. You could therefore spend the $5 generated year after year, in whole or in part, without reducing your initial capital. The same principle applies with the forest: The $5 paid out annually corresponds to the allowable cut that can be harvested without reducing the initial size of the forest.

Over the past ten years, we have harvested on average just 72% of the annual allowable cut available in Quebec’s public forests.(6) We therefore currently harvest less wood than is regenerated each year. Thus, even if we increase this percentage—without exceeding 100% of course—our forests would regenerate more quickly than we harvest them, and it would be possible to create hundreds of millions of dollars of additional wealth each year for rural regions.

This is exactly what some other provinces have done by favouring increased harvest volumes. For example, in British Columbia and in New Brunswick, respectively 96% and 90% of the allowable cut is harvested annually.(7) The residents of these provinces are the beneficiaries, since these harvests are in public forests. In our province, Quebecers collectively own 92% of the forestland, with the remainder accounted for by private forests.(8) In addition to collecting taxes on the economic activity, the government also collects timber royalties for the harvest of public forests, which contributes to the financing of public services.

Moreover, harvesting more wood does not necessarily entail an increase in emissions. On the contrary, research carried out last year by a forests and climate change working group and funded by the Quebec government demonstrated, among other things, that harvesting more wood could capture a lot of CO2 and help reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the province.(9) For example, when wood is transformed into construction materials, the carbon remains trapped longer while the forest regenerates itself. Indeed, the production of alternative construction materials, like steel and cement, requires more fossil fuel energy than the harvest and transformation of wood.(10)

It is therefore not only wrong to say that Quebec forests are threatened and that their area is shrinking year after year; it is also an error to automatically associate the harvesting of lumber with increased GHG emissions in the province.

Increasing the Harvest to Boost the Rural Economy

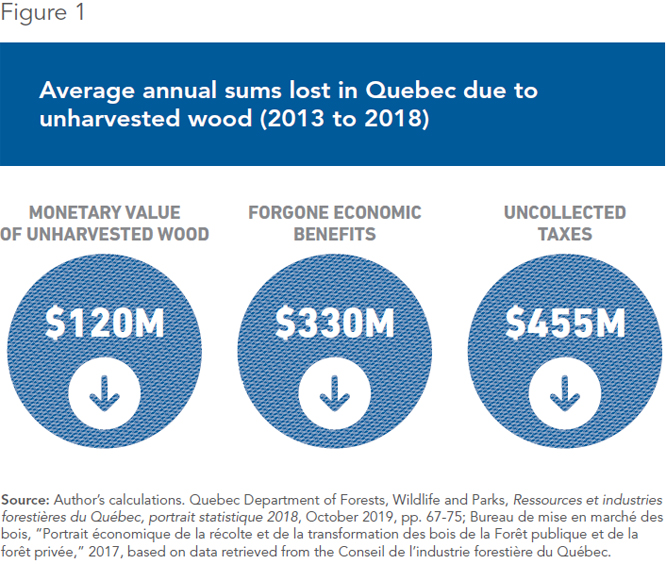

While harvesting a significantly higher proportion of the allowable cut is a medium-term or even a long-term goal, it would be in our interest to begin the process of not leaving millions of dollars in our forests unnecessarily each year. It’s not just a matter of the value of the unharvested wood itself, but also of the foregone economic benefits(11) and the uncollected tax receipts.

As illustrated in Figure 1, Quebec is missing out on several hundreds of millions of dollars in unharvested wood each year. While these sums represent the potential gains if the entire allowable cut was harvested, it is perfectly feasible to develop around 95% of it instead, for example, as British Columbia does. The total area of the provincial forests would continue to grow, and rural regions would reap the economic benefits.

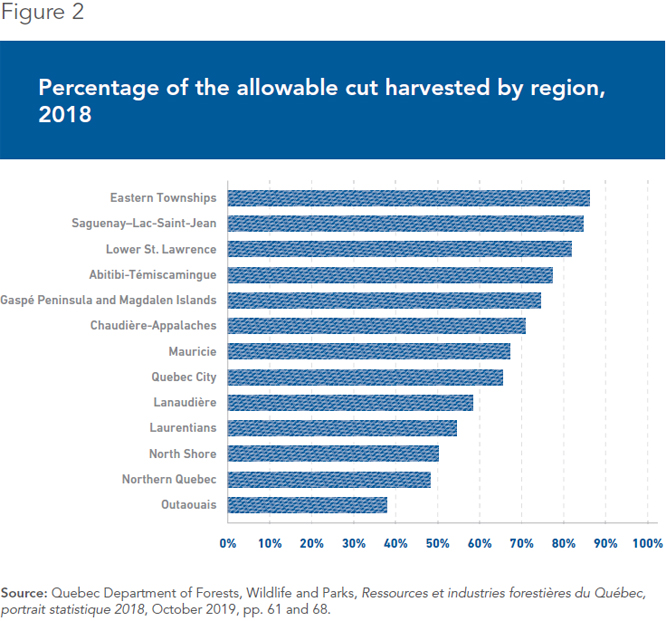

There is regional disparity when it comes to volume of wood harvested (see Figure 2). This is due in part to the quality and species of trees, which vary by region, but also to the regional policies in place. For example, the Saguenay has adopted the province’s first regional timber production strategy, which aims to increase its allowable cut nearly 40% by 2050.(12) Indeed, Quebec’s Chief Forester took a page from this strategy in his 2019 plan when he mentioned wanting to increase the allowable cut for Quebec to 50 million cubic metres in the coming years.(13)

Although the provincial government is a key player in the governance of forest development in Quebec, the regions should also develop strategies specific to their environment in order to facilitate business for the forestry sector in their area. After all, the millions lost each year are a cost primarily for them.

Currently, 25% of the available volume of wood for harvest is auctioned off by the Bureau de mise en marché des bois (BMMB), which is governed by the Department of Forests, Wildlife and Parks.(14) Anyone registering with the BMMB can take part in the auctions, at which the wood is sold as standing timber or as logs. Although this agency’s goal is to reflect market prices through sales at auction, a minimum price is fixed. Thus, not all the wood for sale finds a buyer, as the minimum price required is sometimes too high for the quality of the wood. In other words, the market value of the wood is sometimes lower than the minimum rate set by the BMMB. Except when there are at least three bidders, it is not possible to sell below this rate. This is why 12% of the wood put up for auction between 2013 and 2018 was not sold.(15)

In regions like the North Shore where the wood fibre is often of lower quality, there is often just one company bidding, and given the minimum price, it would have to harvest the wood at a loss if the sale took place. The problem with setting the minimum price too high is that the BMMB prevents companies from harvesting the wood, which in turn means that no taxes are collected. It would be possible to increase tax receipts and economic benefits by reducing the minimum rate, all while generating sales revenue.

In addition to the minimum price mechanism that artificially reduces the volume of wood harvested each year, it would be in everyone’s interest if the government adopted a more effective public forest management plan. The idea is to take better care of the forests in order to increase their productivity. In every province in the country, companies that want to harvest wood in public forests must do this by presenting a forest management plan before work begins.(16) This stipulates the various stages of the forest development plan for the government, and shows how the company will ensure that environmental and replanting standards are respected.

The government should also improve its management plan for undeveloped forests in order to increase the quality of the wood for a future harvest. A public-private partnership could be considered for the purpose of developing a larger area of public forestland. It would be in the interest of municipalities to discuss such partnerships with local companies in order to favour future investment and harvesting activities.

Conclusions and Recommendations

In its 2019-2023 Strategic Plan,(17) the government highlights the importance of increasing the allowable cut and the wood harvest. This corresponds to our own conclusions, and leads us to the following three concrete recommendations:

- The minimum price set by the Bureau de mise en marché must be reviewed and lowered in regions where the wood for sale does not find a buyer;

- The provincial government, the regions, and private forestry companies should collaborate in order to establish a more effective public forest management plan for areas where no development activities are currently taking place;

- It is imperative for the Quebec government to limit the obstacles and costs imposed on forestry companies, for the purpose of achieving a harvest threshold approaching British Columbia’s, namely around 95% of the allowable cut.

The pandemic has had serious consequences for the economies of our rural regions. Concrete measures allowing the private sector to stimulate investment and contribute to the return of economic growth must be a priority. It is in the interest not only of rural Quebec families, but also of all Quebecers, to be able to count on a strong and prosperous forestry sector. It’s time to increase the forestry harvest and stop losing hundreds of millions of dollars every year.

References

- Bureau de mise en marché des bois, Rapport annuel 2018-2019, October 2019, p. 6; Comité sectoriel de main-d’œuvre en aménagement forestier, “Tableau de bord sur l’aménagement forestier et l’emploi de juillet 2019,” September 2020, p. 5.

- Comité sectoriel de main-d’œuvre en aménagement forestier, ibid., p. 6.

- Author’s calculations. Ibid., p. 1.

- Author’s calculations. Ibid., pp. 1-5.

- Author’s calculations. Natural Resources Canada, Forests and forestry, Sustainable forest management, Statistical data, September 2020; Quebec Department of Forests, Wildlife and Parks, Ressources et industries forestières du Québec, portrait statistique 2018, October 2019, p. 1.

- Public forests represent 92% of all forest area in Quebec. Private companies can purchase a permit from the government in order to develop them or purchase wood at auctions run by the Bureau de mise en marché des bois. The total volume of wood harvested in accordance with the permits issued must always be below the allowable cut. Author’s calculations. Quebec Department of Forests, Wildlife and Parks, ibid., pp. 67-75.

- B.C. Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development, Environmental Reporting BC 2018, Trends in Timber Harvest in B.C., updated May 2018, p. 4; B.C. Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development, 2018 Economic State of the B.C. Forest Sector, September 2019, p. 14; New Brunswick Department of Energy and Resource Development, Energy and Resource Development Annual Report 2018-2019, November 2019, p. 9.

- Quebec Department of Forests, Wildlife and Parks, Inventaire écoforestier, September 2020.

- Robert Beauregard et al., Rapport du groupe de travail sur la forêt et les changements climatiques, prepared for the Quebec Department of Forests, Wildlife and Parks, November 15, 2019, p. 1.

- Idem.

- By “economic benefits” we mean the resource owner’s income, companies’ net income before taxes, and the wage bill.

- Quebec Department of Forests, Wildlife and Parks, Stratégie régionale de production de bois, Direction de la gestion des forêts Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean, April 2018, p. 30.

- Quebec’s annual allowable cut is currently 34,148,000 cubic metres. Bureau du Forestier en chef du Québec, Détermination 2018-2023, Synthèse provinciale, November 2019, p. 3; Quebec Department of Forests, Wildlife and Parks, Plan Stratégique 2019-2023, 2019, p. 13. Author’s calculations.

- Bureau de mise en marché des Bois, Le marché libre des bois de la forêt publique du Québec – Bilan quinquennal 2013-2018, May 2019, p. 5.

- Author’s calculations. Idem.

- Natural Resources Canada, Our Natural Resources, Forests and forestry, Sustainable forest management, Forest management planning, June 29, 2020.

- Quebec Department of Forests, Wildlife and Parks, op. cit., note 13.