Examining Canadian Competition in the Digital Era

The Montreal Economic Institute (MEI) is honoured to have been invited to participate in a consultation on the Canadian Competition Act in a continuing effort to ensure Canada has an effective and impactful competition law framework. We have read the discussion paper(1) that examines whether digital markets have distinctive features that would invite significant changes to our competition law, prepared by Professor Edward M. Iacobucci, and wish to comment. While we generally agree with the conclusions reached, there are some points that we believe should be taken into consideration in any future update of the Canadian Competition Act, which we will detail below.

* * *

This brief was prepared by Olivier Rancourt, Economist at the MEI, and submitted during a consultation on the Canadian Competition Act on January 26, 2022.

1) Maximizing Total Surplus

Over the years, multiple antitrust laws have developed a multitude of objectives. Generally, the stated goal is to maximize social welfare. It is, however, hard to quantify what exactly constitutes “social welfare” in an objective sense.

Many methods were created to estimate “social welfare,” most of them imperfect. Some social welfare functions tried calculating the sum of cardinal utilities,(2) and these have been heavily criticized by certain economists as violating some of the methodological constraints of utility.(3) Others, like the Rawlsian social welfare function, which consists of maximizing the utility of the worst member of the studied society,(4) have also been criticized for their conclusions.(5) Because of these difficulties, the method used both in Canada and the United States(6) that is both consistent with economic consensus and can be used on a larger scale is surplus maximization, generally with a cost-benefit analysis.

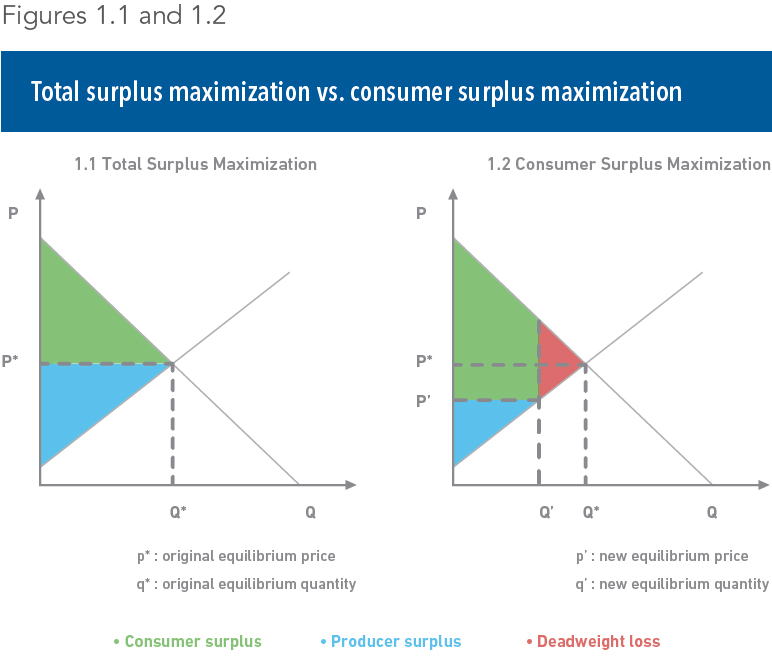

While some countries, like the United States,(7) have chosen to put more weight on consumer surplus maximization, Canada has chosen something that is closer to total surplus maximization.(8) Maximizing the consumer surplus means making sure that the consumer gains the biggest possible share of the economic pie, even if it means having an overall smaller economy. Maximizing the total surplus mean having the biggest possible pie, regardless of who gets what size of slice.(9)

Economically, the only standard should be the maximization of the total surplus. Figure 1.1 depicts total surplus maximization, where supply and demand are at equilibrium at price P* and quantity Q*. As we can see in Figure 1.2, by trying the maximize the consumer surplus and lowering the price (from P* to P’), not only is the economy less prosperous than in Figure 1.1, but some consumers are actually worse off. This is shown by those consumers between Q* and Q’, who would normally be able to buy a product but now cannot since the supply is lower at the new equilibrium (P’, Q’). So, despite the fact that those who are able to obtain the product might have a higher utility, the consumers between Q* and Q’ are worse off economically as a result of the government intervention.

Economically, it doesn’t matter if the gain goes to the consumer or the producer, as long as there is a gain. Any other standard would simply end up hurting Canadian wealth creation in the long term. As antitrust laws aim to ensure a fairer and more efficient economic system,(10) it is vital to maintain this standard. After all, every unit of output created for the Canadian economy is good for it, regardless of whether it’s the consumer or the shareholder that’s earning it. Therefore, focusing on maximizing anything other than the total surplus would create a deadweight loss and result in some Canadians being worse off.

2) The Efficiency Criteria

As was mentioned by Professor Iacobucci(11) and other economists,(12) the only criteria that should matter economically is efficiency. As Canadian courts have also concluded, using efficiency has a criterion means that the goal of antitrust laws should be to minimize economic deadweight losses,(13) thus trying to maximize total surplus.(14) The inclusion of any other criteria creates confusion on the goals of antitrust laws, both for enforcement agencies and for companies themselves. Even worse, some of these additional criteria might actually contradict themselves. For example, in some cases, the pursuit of other objectives can hurt the efficiency of markets if the economies of scale outweigh the efficiency gain of competition.(15)

These analyses should also be made based on “dynamic efficiency,” with a temporal outlook. As mentioned in the report, sometimes looking only at the present situation is misleading.(16) For example, a company that just innovated might seem to be in a monopoly situation because no new player has had the time to create a product that could compete with it. Using dynamic efficiency is a good way to consider a change in consumer preference that might happen after an innovative breakthrough.(17) It is important to try to maximize long-term wealth creation and innovation, and using dynamic efficiency is seen as an important economic tool to obtain long-term growth by stimulating innovation.(18)

On the other hand, a company might be doing things that are not anticompetitive in isolation, but that might bring about anticompetitive results at a later date. For example, some companies might want to buy out innovative firms to prevent them from developing products that might threaten their revenue base.(19) By ensuring that dynamic efficiency is enforced, actions that may stop the creative destruction of innovation might be corrected. By enshrining into law the dynamic efficiency criterion, the law would thus work to promote innovation and maximize total surplus.

The use of the dynamic efficiency criterion is thus the best way to maximize innovation and growth, while ensuring an efficient system. This doesn’t mean that other criteria should not be used, but they should always come second to the maximization of efficiency. By making it clear that the primary goal is the maximization of the total surplus via a dynamic efficiency criterion, not only would the law be easier to enforce, but it would also help the Canadian economy grow in the mid- to long term, making Canadians more prosperous.

3) Multi-Sided Firms

Professor Iacobucci mentions that the Competition Act is currently flexible enough to deal with digital companies.(20) We agree. However, one of the aspects that distinguishes many modern digital firms from most traditional ones is their multi-sided nature. Multi-sided firms are companies that have multiple distinct consumer bases, with at least one of them requiring the presence of another to derive utility from the product.(21)

Companies like Facebook/Meta or Google/Alphabet have multiple complementary consumer bases. The “advertiser” user requires a large “consumer” user base for them to obtain a gain in using these platforms, and without the “advertiser,” the platform cannot be free for the “consumer.” Every type of user should be considered when analyzing the efficiency criteria, since a measure that may seem to benefit one user base might have unintended negative consequences on another, or even on the same user base that initially benefited, and end up hurting it in the long term.

It is therefore important for the law and regulations to take all types of consumers into consideration when trying to maximize total surplus. Many types of two-sided platforms charge one type of consumer, while giving the other type of consumer access to the service for a lesser price, or even free.(22) In these situations, a potential merger could hurt the welfare of one group of consumers whilst increasing the welfare of the other group. Therefore, without considering all of these aspects and impacts, total surplus could be significantly diminished, even though the surplus for one type of consumer might be higher. This could also end up impacting other markets, since some of the consumers for multi-sided platforms are also producers in other markets. Therefore, many different markets could suffer at the same time.

Another aspect of these platforms is the high interconnectivity between the different consumer types, which has the potential to create negative feedback loops. For example, if the readership of a newspaper diminishes, advertisers will be less inclined to pay for advertising in this space, which could result in further reductions in readership. Or, if a merchant stops accepting a certain type of credit card, the consumer may change their shopping habits, which could lower the profitability of the merchant and further lower the probability of a merchant accepting the card in the future.

These platforms are at risk of being rapidly replaced if, for some reason, one (or both) consumer types desert them. This high volatility creates a market that is highly vulnerable to creative destruction. Implementing the dynamic efficiency criterion suggested above would alleviate concern over the size of these companies.

Enforcement should thus take into consideration the multi-sided nature of these platforms. Going down the most obvious path and acting as if they were normal platforms would actually hurt many Canadian consumers and businesses. By including consideration for these platforms, Canadian antitrust laws would work for the benefit of all Canadians.

4) Taking Other Factors into Account

In Canada, some sectors are heavily regulated, such as the airline industry. It has been estimated that between 22% and 35% of the Canadian economy is constrained by some kind of state-imposed barriers to entry.(23) One of the consequences of such regulation is to make it harder for new companies to enter a market, and therefore to give greater market power to firms already in place.

If a firm’s market power is due to previously existing regulations, the court should be able to strike down such government regulations without using antitrust laws, especially since the economic consensus is clear: many governmental regulations only end up increasing companies’ market power without benefiting the consumer.(24)

Punishing firms for market power due to government regulations is simply counterproductive. The laws should make a clear exception for cases where the market power comes from previous government regulation. Therefore, the optimal action would not be to use the antitrust provisions, but instead to dismantle the problematic regulations that create these situations to begin with.

5) The Burden of Proof for Quantitative Inefficiencies in Mergers

Professor Iacobucci is of the opinion that the precedent of the Tervita case, which determined that the Competition Bureau had to quantify the anticompetitive effect of a merger, including the potential efficiency gains, should be overturned.(25) While we agree that the current situation in which enforcement agencies have to prove the validity both of their own claims and of the defence is absurd, we disagree that the burden of proof should be on the defendants.(26) We believe that the party making a claim concerning a company’s efficiency—or lack thereof—should be the one that has to prove it.

Anything else would go against the presumption of innocence that is central to our justice system. If the regulatory agency thinks that a company is breaking antitrust laws, it should be the regulatory agency that is required to prove it. If the Competition Bureau is making an antitrust claim against an enterprise, it should be the one proving the anticompetitive effects. If a company affirms that a merger and acquisition will result in an efficiency gain, they should be the one proving it. The burden of proof should be on the shoulders of those making the affirmations. This would facilitate the work of both the prosecution and the defence, since both would have access to the data that substantiates the claim. Any other “unquantifiable” effect should be left to the discretion of the court.

An Antitrust Law That Benefits All Canadians

The update of the Canadian antitrust law is an important opportunity for Canada to become a leader in fostering innovation and economic growth. We believe that if the Act is amended so that the sole criterion is to maximize total surplus, using a dynamic efficiency criterion, this would help to ensure Canada is a safe haven for entrepreneurs and innovation, while also seeking to maximize the economic pie for everyone. We also are in agreement with Professor Iacobucci in thinking that the current antitrust laws are sufficient to deal with the new technological giants. We believe, however, that enforcement should take into consideration the multi-sided nature of most of these platforms to be sure not to indirectly penalize some of society in an attempt to help another.

We also believe that the court should have the power to dismiss laws and regulations that create economic conditions that are in opposition with the Competition Act, instead of trying to correct the matter with antitrust statutes. Finally, we disagree with Professor Iacobucci’s assessment of the Tervita case. We believe that the burden of proof should be on whoever is making the assertion. If the Competition Bureau is pushing for an antitrust case against a company, it should be the Bureau that has to prove this antitrust risk.

References

- Edward M. Iacobucci, “Examining the Canadian Competition Act in the Digital Era,” September 2021.

- Cardinal utility is the idea that economic welfare can be directly observable and given a value.

- John C. Harsanyi, “Cardinal Welfare, Individualistic Ethic, and Interpersonal Comparisons of Utility,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 63, No. 4, August 1955, p. 309.

- John C. Harsanyi, “Can the maximin principle serve as a basis for morality? A critique of John Rawls’s theory,” American Political Science Review, Vol. 69, No. 2, June 1975, p. 595.

- Ibid., pp. 604-605.

- Thomas W. Ross and Ralph A. Winter, “A Canadian Perspective on Vertical Merger Policy and Guideline,” Review of Industrial Organisation, Vol. 59, June 2021, p. 230.

- Ibid., pp. 230 and 249.

- Ibid., pp. 239-240.

- Jake Edmiston, “‘Holy battle’: Competition Bureau chief readies for fight to shake up merger laws,” Financial Post, November 12, 2021.

- Competition Act, R.S.C., 1985, c. C-34, article 1.1.

- Edward M. Iacobucci, op. cit., note 1, p. 72.

- John R. Carter, “Collusion, Efficiency, and Antitrust,” The Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 21, No. 2, October 1978, pp. 435-436.

- Edward M. Iacobucci, op. cit., note 1, p. 50.

- Thomas W. Ross and Ralph A. Winter, op. cit., note 6, pp. 240-241.

- John R. Carter, op. cit., note 12, p. 441.

- Edward M. Iacobucci, op. cit., note 1, p.36.

- Gaël Campan, “A Sound Competition Approach Supports Air Canada’s Acquisition of Air Transat,” Economic Note, MEI, March 2020, pp. 1-2.

- Melissa A. Schilling, “Towards Dynamic Efficiency: Innovation and its Implication for Antitrust,” The Antitrust Bulletin, Vol. 60, No. 3, September 2015, p. 206.

- Edward M. Iacobucci, op. cit., note 1, p. 36.

- Ibid., p. 3.

- David S. Evans, “The Antitrust Economics of Multi-Sided Platform Markets,” Yale Journal on Regulation, Vol. 20, No. 2, September 2002, p. 325.

- Ibid., p. 337.

- Vincent Geloso, “Walled from Competition: Measuring Protected Industries in Canada,” Fraser Institute, 2019, pp. 13-15.

- William A. Jordan, “Producer Protection, Prior Market Structure and the Effects of Government Regulation,” The Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 15, No. 1, April 1972, pp. 174-176.

- Edward M. Iacobucci, op. cit., note 1, p. 29.

- Ibid., p. 33.