Canada Shows the Way on Stock Markets

Canada has avoided the great die-off of public companies afflicting American business especially since the 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley Act, which imposed new, more restrictive accounting and financial transparency rules. But with trends reversing somewhat since 2012, much work remains to be done in Canada to promote access to investment opportunities for the middle class. This would not only further democratize wealth-building for regular Canadians, but also give start-ups even greater ability to raise funds to grow their business.

* * *

This Viewpoint was prepared by Peter St. Onge, Senior Economist at the MEI, and Michel Kelly-Gagnon, President and CEO of the MEI. The MEI’s Regulation Series aims to examine the often unintended consequences for individuals and businesses of various laws and rules, in contrast with their stated goals.

Canada has avoided the great die-off of public companies afflicting American business especially since the 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley Act, which imposed new, more restrictive accounting and financial transparency rules. But with trends reversing somewhat since 2012, much work remains to be done in Canada to promote access to investment opportunities for the middle class. This would not only further democratize wealth-building for regular Canadians, but also give start-ups even greater ability to raise funds to grow their business.

The Decline of U.S. Public Markets

Public markets in the United States are increasingly closed to regular investors. One indication of this is that in 1995, Yahoo held an initial public offering just one year after incorporation, while it took Amazon just three years to go public after Jeff Bezos founded his online bookstore. In contrast, this year’s IPO darlings, Airbnb and Uber, were founded in 2008 and 2009.

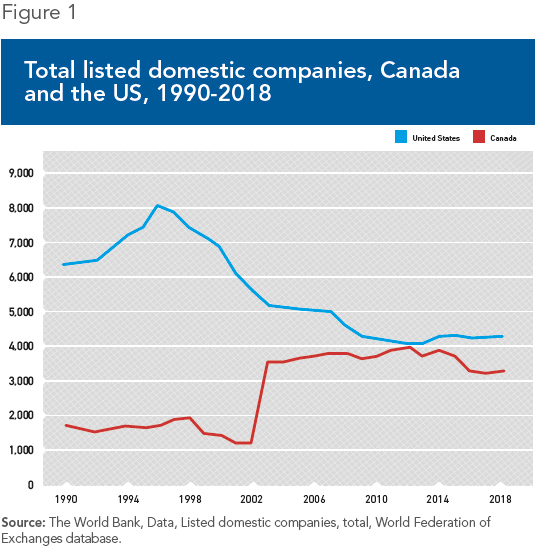

But America’s problem goes much deeper than delayed IPOs: The number of companies listed on public markets has plunged by about half since the 1990s, and by nearly a quarter just since the 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley bill.(1) Canada’s public listings, meanwhile, soared in the wake of this major reform, almost tripling in the first year and continuing to climb in the ensuing decade (see Figure 1).

The decline in American public listings echoes across the start-up world. In 1996, public markets were the primary outlet (70%) for venture capital investors, but today, roughly 85% of such exits are via mergers and acquisitions. Meanwhile, the size of the average listed company in America has increased substantially since the 1990s.(2) Taken together, these signs show that American public markets are increasingly a plaything of the rich, closed to regular investors who don’t have the million-dollar minimum investments needed before a venture capital fund manager will even return their phone calls.(3)

Some academics say this is the new norm. In a 2018 article, researchers from Columbia, Dartmouth, and the University of Calgary concluded that software and the internet have cut costs to the point that start-ups can bootstrap themselves without public markets.(4) Yet this conclusion is starkly belied by Canada’s experience. In fact, Canada now has fully 75% as many listed firms as the US, despite a population one-ninth as large. Meanwhile, capital investment as a percentage of GDP has soared, outstripping US levels by almost 15% in 2017.(5)

Given that Canada, too, has software and internet, something else must be going on. A strong clue for the Canada-US divergence can be gleaned from the post-Sarbanes jump. Indeed, Canada’s Bill C-198, passed as a response to Sarbanes-Oxley, is much less threatening.

Under this law, Canadian companies must provide only a “reasonable assurance” against misstatements, unlike the US requirement to safeguard against even a “remote chance” of misstatement.(6) The US auditing board has been far more aggressive, even sometimes conducting annual inspections of auditors themselves.(7) Overall, Canadian regulators have a lighter touch, which cuts compliance costs and makes it easier for firms to list. It can cost as little as $50,000 to list on the TSX-Venture exchange and requires only $500,000 in annual revenue.(8) The comparable US thresholds are several times as high.

Indeed, both costs and risks are soaring in the US. Three-quarters of companies surveyed by PwC spend over US$1 million annually simply to maintain a public listing, on top of the one-time costs for the typical IPO, which average from US$10 million to US$34 million depending on company size.(9) This alone pushes out small business. More ominously, aggressive statement policing(10) may scare away innovation, which is risky, after all, and usually entails more than a “remote chance” of mistakes.

The US would benefit if its regulators took a cue from Canada and adopted a less confrontational approach with lower compliance costs—lest regulators end up killing the public markets they are supposed to protect.

A Boost for Canadian Start-Ups

While Canadians have a right to be proud of their prudent regulators, there remains much work to be done. In the past six years, the relative trend has reversed, with Canadian public listings falling 17% while American listings have risen 7%. Rising compliance costs, intrusion into corporate governance such as executive compensation, and the rise in shareholder lawsuits suggest Canada risks following the path blazed by America.

Bill C-198 has empirically been much better for public markets than Sarbanes-Oxley, yet it nevertheless imposes burdens and risks on public firms, raising auditing costs beyond previous approaches, while easing the way for more US-style lawsuits.(11) As one Australian Stock Exchange observer noted during the debate on the Canadian measure back in 2003, “If it’s sick in New York, it seems the world must find a cure.”(12) Bill C-198 may be a needless reaction to an American problem that nevertheless burdens Canadian companies.

Merely avoiding other countries’ worst mistakes isn’t the end-goal of public policy. America is learning that placing burdens on public companies can be counterproductive. Canada, by targeted reduction of burdens and risks for public companies, can build on that lesson. Doing so would help bring more investing opportunities to regular Canadians, and bring additional investment dollars to the Canadian start-ups that need them.

References

1. The Global Economy, Compare countries with annual data from official sources, Stock market development, Listed companies.

2. “Where Have All the Public Companies Gone?” Bloomberg, April 9, 2018.

3. Lorna Tan, “Investing in venture capital funds: Do your homework first,” The Straits Times, June 25, 2017.

4. Vijay Govindarajan et al., “Why We Shouldn’t Worry about the Declining Number of Public Companies,” Harvard Business Review, August 27, 2018.

5. The Global Economy, Canada: Capital investment, percent of GDP; The Global Economy, USA: Capital investment, percent of GDP.

6. Compliance Online, Sarbanes-Oxley vs. Bill 198 – Key Differences, May 21, 2010.

7. Charles Levinson, “Accounting industry and SEC hobble America’s audit watchdog,” Reuters, December 16, 2015.

8. Alixe Cormick, “Listing Requirements of the TSX Venture Exchange (TSX-V) – Industrial, Technology, Life Sciences, Real Estate and Investment Companies,” Venture Law Corporation, July 10, 2018; Matthew Sherwood, “Should your company list on the Venture Exchange?” The Globe and Mail, May 27, 2013 (updated May 11, 2018).

9. Derek Thomson, “Considering an IPO to fuel your company’s future? Insight into the costs of going public and being public,” PwC, November 2017.

10. Jonathan Macey, “As IPOs decline, the market is becoming more elitist,” Los Angeles Times, January 10, 2017.

11. Grey Swan Advisory Professional Corporation, Secondary Market Actions (“Bill 198”): Where Are We Now?

12. Doug Watt, “Canada should think twice about Sarbanes-Oxley, experts say,” Advisor’s Edge, September 8, 2003.