Taxing Sugar Will Not Halt the Rise in Obesity

Earlier this year, the Quebec government formed a committee whose stated goal was to propose a soda tax, for the purpose of reducing the prevalence of obesity. Yet there are numerous reasons to question the effectiveness of this measure. Indeed, when a tax modifies the price of a good, there is no guarantee that the replacement product will be better for one’s health than the taxed product.

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| L’obésité augmente même si on consomme moins de sucre (The MEI’s Journal de Montréal blog, November 27, 2018) | Interview (in French) with Mathieu Bédard (Isabelle, 98,5 FM, November 27, 2018)

Interview (in French) with Mathieu Bédard (Le retour d’Éric Duhaime, FM93, November 27, 2018) |

Report with Mathieu Bédard (CTV News Montreal 6:00PM, CFCF-TV, November 27, 2018)

Interview with Mathieu Bédard (CTV News Montreal 12:00PM, CFCF-TV, November 29, 2018) |

This Viewpoint was prepared by Mathieu Bédard, Economist at the MEI. The MEI’s Taxation Series aims to shine a light on the fiscal policies of governments and to study their effect on economic growth and the standard of living of citizens.

Earlier this year, the Quebec government formed a committee whose stated goal was to propose a soda tax, for the purpose of reducing the prevalence of obesity.(1) Yet there are numerous reasons to question the effectiveness of this measure. Indeed, when a tax modifies the price of a good, there is no guarantee that the replacement product will be better for one’s health than the taxed product.

The Paradox of Sugar

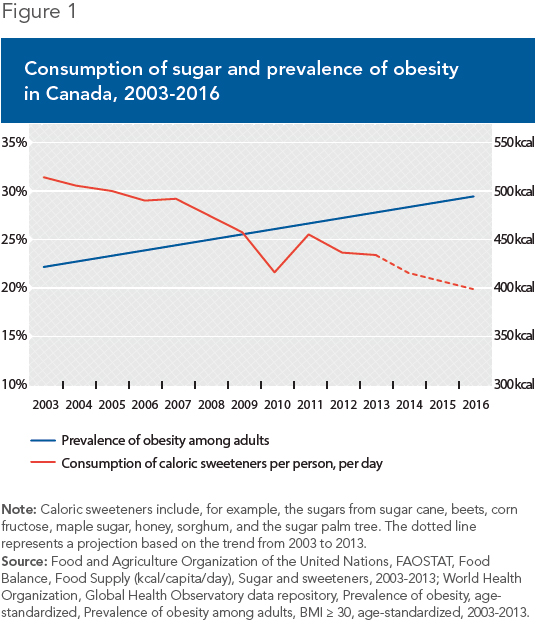

Sugar is not the cause of rising rates of obesity.(2) In fact, a “sugar paradox” can be observed in Quebec and in the rest of Canada, as well as in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia, among others. In all of these places, there has been an increase in obesity in recent years, despite the fact that sugar consumption is down.(3)

A recent study shows, for example, that despite the increased prevalence of obesity, Quebecers and other Canadians consume fewer and fewer sugary drinks, and those they do consume contain less and less sugar.(4) The consumption of sugar in general has also fallen over the past ten years, after having risen almost constantly since the early 1990s. Despite this, the obesity “epidemic” has maintained its momentum, and today affects nearly a third of the country’s population (see Figure 1).

The same phenomenon can be observed elsewhere. In the United States, the consumption of sugar and its equivalents (including the high-fructose corn syrup used in soft drinks) has fallen since the late 1990s, contrary to popular belief. The obesity rate, though, keeps rising.(5) In Aus-tralia, where this connection has been widely commented on, the increase in the prevalence of obesity has coincided with a substantial drop in sugar consumption.(6)

The Problem Is Calories

Numerous clinical studies have demonstrated that there is nothing special about sugar in itself that would slow down or cancel out weight loss while dieting.(7) As nutritional science explains, it is the overconsumption of calories, whatever their origin, that leads to weight gain, whether one eats whole foods, processed foods, or sugary drinks. This is an important point, as it is thus technically possible to lose weight while consuming sugary foods and drinks almost exclusively.

Focusing on a single type of food or a single nutrient to deal with the problem of obesity is doomed to failure.(8) This is a case of the economic principle of unintended consequences, as illustrated in the United States when Oregon banned chocolate milk from elementary school cafeterias. A study found that less milk was thus sold, that more of the milk sold was wasted, and that many students stopped buying meals at school.(9) The net result was that less milk was consumed and, the researchers suspect, this was compensated for at snack time or after school with foods or drinks that were just as calorific.

The problem with taxing food that is too sweet, too salty, or too fatty is the same as for all taxation. When you tax a product, behaviours change, and people substitute their consumption of one good for that of another.(10) The effect of a hypothetical tax on the prevalence of obesity will depend, though, on what replaces sugary drinks.

If, despite the tax, people continue to consume too many calories, this public policy will have no effect. It will nonetheless have increased the prices of products, which is particularly pernicious for the less well-off. And if the total consumption of sugar is relatively or completely unaffected, it’s even worse, since such a policy can then not even claim to improve public health. On the contrary, it might actually undermine it. This would be the case if, due to the tax, people sacrificed a portion of their healthy consumption of milk, for example, or of fruits and vegetables, in order to maintain their consumption of sugary drinks.

The same problem would arise if it were a question of taxing processed foods, which are also sometimes accused of being responsible for the increase in obesity. For example, one study found that processed foods contained 55% of the dietary fibre in the diets of Americans, as well as 48% of their calcium intake, 43% of their potassium, 34% of their vitamin D, 64% of their iron, 65% of their folic acid, and 46% of their vitamin B-12.(11) If a tax led Americans to replace processed foods in their diets, there is no guarantee that what would replace them would be as rich in these nutrients, or less calorific for that matter. In sum, such a tax could well have a negative effect on their diets.

Conclusion

Nutrition, and consumption more generally, is more complex than we think. If we were to try to modify Quebecers’ food-related behaviours using taxes, it would be impossible to know with certainty what they would shift their consumption to. Simplistic solutions like taxing sugary drinks do not address more basic problems, like adequate education about good nutrition and a healthy lifestyle, for which a tax is no substitute.

References

1. Pierre Couture, “Bientôt une taxe sur les boissons sucrées,” Le Journal de Montréal, March 20, 2018.

2. James M. Rippe and Theodore J. Angelopoulos, “Sugars and Health Controversies: What Does the Science Say?” Advances in Nutrition, Vol. 6, No. 4, July 1st, 2015, pp. 493S-503S.

3. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, FAOSTAT, Food Balance, Food Supply (kcal/capita/day), Sugar and sweeteners, 2003-2013; World Health Organization, Global Health Observatory data repository, Prevalence of obesity, age-standardized, Prevalence of obesity among adults, BMI ≥ 30, age-standardized, 2003-2013.

4. Michael Grant, Counting the Calories: Examining the Relationship Between Beverage Consumption and the Canadian Diet, The Conference Board of Canada, July 2018.

5. USDA, Food Availability (Per Capita) Data System, Caloric sweeteners: Per capita availability adjusted for loss, 1990-2016; World Health Organization, Global Health Observatory data repository, Prevalence of obesity, age-standardized, Prevalence of obesity among adults, BMI ≥ 30, age-standardized, 1990-2016.

6. Alan W. Barclay and Jennie Brand-Miller, “The Australian Paradox: A Substantial Decline in Sugars Intake over the Same Timeframe that Overweight and Obesity Have Increased,” Nutrients, Vol. 3, No. 4, 2011, pp. 491-504; Alan W. Barclay and Jennie Brand-Miller, “Declining Consumption of Added Sugars and Sugar-Sweetened Beverages in Australia: A Challenge for Obesity Prevention,” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Vol. 105, No. 4, April 2017, pp. 854-863; Bradley Ridoutt et al., “Changes in Food Intake in Australia: Comparing the 1995 and 2011 National Nutrition Survey Results Disaggregated into Basic Foods,” Foods, Vol. 5, No. 2, 2016, article 40; Linggang Lei et al., “Dietary Intake and Food Sources of Added Sugar in the Australian Population,” British Journal of Nutrition, Vol. 115, No. 5, March 2016, pp. 868-877; Australian Bureau of Statistics, Consumption of Added Sugars − A Comparison of 1995 to 2011-12, December 13, 2017.

7. JA. West and A.E. de Looy, “Weight Loss in Overweight Subjects Following Low-Sucrose or Sucrose-Containing Diets,” International Journal of Obesity, Vol. 25, No. 8, August 2001, pp. 1122-1128; R.S. Surwit et al., “Metabolic and Behavioral Effects of a High-Sucrose Diet During Weight Loss,” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Vol. 65, No. 4, April 1997, pp. 908-915; Susan K. Raatz et al., “Reduced Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load Diets Do Not Increase the Effects of Energy Restriction on Weight Loss and Insulin Sensitivity in Obese Men and Women,” The Journal of Nutrition, Vol. 135, No. 10, October 2005, pp. 2387-2391; E.E.J.G. Aller et al., “Weight Loss Maintenance in Overweight Subjects on Ad Libitum Diets with High or Low Protein Content and Glycemic Index: The DIOGENES Trial 12-Month Results,” International Journal of Obesity, Vol. 38, December 2014, pp. 1511-1517.

8. Joanne Slavin, “Two More Pieces to the 1000-Piece Carbohydrate Puzzle,” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Vol. 100, No. 1, July 2014, pp. 4-5.

9. Andrew S. Hanks, David R. Just, and Brian Wansink, “Chocolate Milk Consequences: A Pilot Study Evaluating the Consequences of Banning Chocolate Milk in School Cafeterias,” PLOS ONE, Vol. 9, No. 4, April 2014.

10. David Gratzer and Jasmin Guénette, No Magic Pill: Positive Solutions to the Obesity Issue, Research Paper, MEI, May 2013, pp. 13-16.

11. Connie M. Weaver et al., “Processed Foods: Contributions to Nutrition,” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Vol. 99, No. 6, June 2014, pp. 1525-1542.