The Minimum Wage: Ontario Was Right to Cancel the Hike to $15

Many politicians and interest groups advocate a rapid increase in the minimum wage in the name of social justice. Yet this ignores the results of past experiments. Ontario’s new Minister of Labour, Laurie Scott, pushed back by cancelling the increase to $15 planned for January 2019, and by stating that the minimum wage should be determined “by economics, not politics.” Subsequent increases will be set based on the annual change in the cost of living. This is a reasonable compromise, which will avoid further harming workers at the bottom of the ladder, and more specifically the young.

Media release: The minimum wage in Ontario: Already over 56,000 jobs lost among province’s youth

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| An end to minimum-wage politics (National Post, November 20, 2018)

Salaire minimum : l’Ontario a bien fait d’annuler la hausse à 15$ (Huffington Post Québec, November 21, 2018) |

Interview (in French) with Alexandre Moreau (Midi Pile, CKYK-FM, November 20, 2018) | Interview with Alexandre Moreau (The Real Economy, BNN, November 20, 2018) |

This Viewpoint was prepared by Alexandre Moreau, Public Policy Analyst at the MEI. The MEI’s Regulation Series aims to examine the often unintended consequences for individuals and businesses of various laws and rules, in contrast with their stated goals.

Many politicians and interest groups advocate a rapid increase in the minimum wage in the name of social justice.(1) Yet this ignores the results of past experiments. Ontario’s new Minister of Labour, Laurie Scott, pushed back by cancelling the increase to $15 planned for January 2019, and by stating that the minimum wage should be determined “by economics, not politics.”(2) Subsequent increases will be set based on the annual change in the cost of living.(3) This is a reasonable compromise, which will avoid further harming workers at the bottom of the ladder, and more specifically the young.

The minimum wage previously jumped from $11.60 to $14 in Ontario at the start of 2018. Adverse effects are already being felt, despite the strength of the economy.(4) This can be explained by the substantial increase in the ratio of the minimum wage to the average wage. Quebec’s experience during the 1970s showed, among other things, that the number of jobs fell if this ratio was too high.(5)

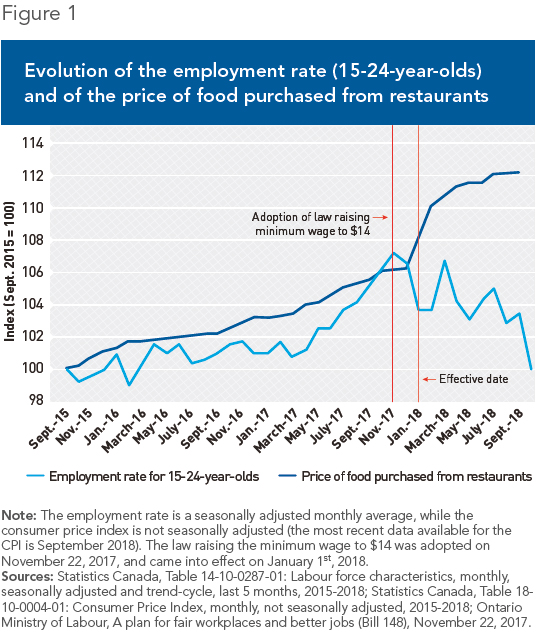

In Ontario, the January 2018 increase bumped this ratio up from 43% to 51% of the average hourly wage, far above the 45% threshold that limits the effects on employment. (The increase planned for 2019 would have pushed it up to around 54%.)(6) It is therefore not surprising to find that the employment rate among workers between 15 and 24 years of age, which had been trending upward for quite some time, fell when the minimum wage law was adopted in November 2017 (see Figure 1). Thus, 56,100 workers aged 15 to 24 lost their jobs between the law’s adoption and October 2018.(7)

Furthermore, between the law’s adoption and September 2018, there has been a 5.6% increase in the prices of meals in restaurants,(8) a sector in which nearly 70% of workers earned less than $15 an hour before adoption.(9) This price increase is over three times greater than that observed in the other provinces over the same period.(10) Such a variation is consistent with past experiments, which show that restaurants quickly pass on practically all additional costs to consumers.(11)

Finally, we can also expect the impacts of the minimum wage hike to have been greater in rural regions, where the average wage is generally lower. Workers who live there are thus more at risk of losing their jobs, or of having their hours or their benefits cut.(12)

No Poverty Reduction

While it may seem paradoxical, practically all studies show that a substantial increase in the minimum wage does not reduce poverty; it mostly affects people who are not in low-income situations, and it even contributes to an increase in poverty due to the jobs that it destroys.(13) A report from the Financial Accountability Office of Ontario on the effect of raising the minimum wage to $15 concurs, estimating moreover that it would entail a net loss of at least 50,000 jobs in the province.(14)

According to a study based on the Canadian experience, only a quarter of wage gains are directed toward workers who are below the poverty line. Taking into account the ensuing job losses, the authors conclude that a minimum wage increase has no net effect on poverty.(15) Another study on the Canadian case arrives at the conclusion that a 10% hike in the minimum wage is associated with an increase of 4% to 6% in the number of households in low-income situations, since job losses for young workers reduce incomes for these households.(16)

Moreover, 60% of workers earning minimum wage in Ontario are between the ages of 15 and 24, and the majority of these are students living with their parents. Among all minimum wage workers, only 2.1% are single parents with young children.(17)

It is mainly young workers and immigrants of all ages who suffer the adverse effects associated with a large and too-rapid increase in the minimum wage. The scientific literature is quite unanimous in this regard,(18) and the debates that persist deal more with the size of these negative consequences as a function of the level of productivity, the structure of the labour market, and the size of the increase.(19)

Cancelling the planned January 2019 increase was therefore, from an economic point of view, the only decision the Ontario government could make. Furthermore, determining future increases as a function of the evolution of the cost of living will depoliticize them and make them more predictable for companies.

Conclusion

No one doubts the good intentions of those who continue to call for rapidly increasing the minimum wage in all circumstances, but that does not make it an effective measure for reducing poverty. There are other ways of doing so, including raising the basic income tax exemption, reducing the barriers that restrict access to the labour market, or even increasing the tax benefit for low-income workers who need to support themselves.(20) These are the kinds of things we should be looking at, if the purpose is to help these people.

References

1. Ontario Liberal, A $15 Minimum Wage and Fairer Workplaces; Josh O’Kane and Justin Giovannetti, “Cheers, criticism greet Ontario plan to raise minimum wage to $15,” The Globe and Mail, May 30, 2017.

2. Greg Davis, “Ontario Minister of Labour’s constituency office in Lindsay vandalized overnight,” Global News, October 24, 2018.

3. Government of Ontario, Bill 47: An Act to amend the Employment Standards Act, 2000, the Labour Relations Act, 1995 and the Ontario College of Trades and Apprenticeship Act, 2009 and make complementary amendments to other Acts, October 23, 2018.

4. Ontario Ministry of Finance, Ontario Economic Accounts, Second Quarter of 2018, Table 15: Ontario production by industry at 2007 prices, Seasonally adjusted data at annual rates, millions of chained (2007) dollars, 2015-2018, p. 37.

5. Pierre Fortin, “Salaire minimum, pauvreté et emploi : à la recherche du ‘compromis idéal’,” Regards sur le travail, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2010, p. 1.

6. See the Technical Annex on the MEI’s website.

7. The variation is based on seasonally adjusted data. Statistics Canada, Table 14-10-0287-01: Labour force characteristics, monthly, seasonally adjusted and trend-cycle, last 5 months, November 2017 to October 2018.

8. The increase immediately followed the law’s entry into force. Aleksandra Sagan, “Ontario restaurant price hikes boost food inflation after minimum wage increase,” Financial Post, February 23, 2018.

9. Financial Accountability Office of Ontario, “Assessing the Economic Impact of Ontario’s Proposed Minimum Wage Increase,” Commentary, September 12, 2017, p. 3.

10. The period goes from December 2017 to September 2018, the most recent available data at the time of writing. See the Technical Annex.

11. See the “Effect of the Minimum Wage on Prices” section in the Technical Annex.

12. Mathieu Bédard and Alexandre Moreau, “Would a $15 Minimum Wage Accelerate the Rural Exodus?” Economic Note, MEI, December 2016.

13. See the “Effect of the Minimum Wage on Poverty” section in the Technical Annex.

14. Financial Accountability Office of Ontario, op. cit., endnote 9, p. 1.

15. Michele Campolieti, Morley Gunderson, and Byron Lee, “The (Non) Impact of Minimum Wages on Poverty: Regression and Simulation Evidence for Canada,” Journal of Labor Research, September 2012, Vol. 33, No. 3, pp. 287-302.

16. Anindya Sen, Kathleen Rybczynski, and Corey Van De Waal, “Teen Employment, Poverty, and the Minimum Wage: Evidence from Canada,” Journal of Labour Economics, Vol. 18, No. 1, January 2011, pp. 36-47.

17. Charles Lammam and Hugh MacIntyre, “Increasing the Minimum Wage in Ontario: A Flawed Anti-Poverty Policy,” Research Bulletin, Fraser Institute, June 2018, pp. 5-6.

18. See the “Effect of the Minimum Wage on Young Workers” section in the Technical Annex.

19. For more on the debate surrounding the effect of the minimum wage on employment, see Vincent Geloso, “Le salaire minimum fait toujours aussi mal,” Le Journal de Montréal, June 14, 2016. See also Michael Christl, Monika Köppl-Turyna, and Denes Kucsera, “Revisiting the Employment Effects of Minimum Wages in Europe,” German Economic Review, Vol. 19, No. 4, pp. 426-465; Aspen Gorry and Jeremy J. Jackson, “A Note on The Nonlinear Effect of Minimum Wage Increases,” Contemporary Economic Policy, Vol. 35, No. 1, January 2017, pp. 53-61.

20. Sean Speer and Rob Gillezeau, “Expanding the Working Income Tax Benefit Should Appeal to All Parties,” Macdonald-Laurier Institute, December 7, 2016.