Higher Education: The True Cost of “Free” Tuition

The idea of making higher education “free” in Quebec is hardly new, but recently, some politicians have revived the debate by promising to implement such a policy if elected. While this idea may seem attractive at first glance, it would be costly for Quebec taxpayers, would not necessarily lead to more students graduating, and would also be unfair.

Media release: Higher education: “Free” tuition would cost $1.3 billion

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| ‘Free’ university tuition would be bad for Quebecers (Montreal Gazette, August 16, 2018)

Droits de scolarité postsecondaire – Vous avez dit « gratuit »? (La Presse+, August 16, 2018) |

Interview (in French) with Alexandre Moreau (Maurais Live, CHOI-FM, August 17, 2018) |

This Viewpoint was prepared by Alexandre Moreau, Public Policy Analyst at the MEI, in collaboration with Miguel Ouellette, Researcher at the MEI. The MEI’s Education Series aims to explore the extent to which greater institutional autonomy and freedom of choice for students and parents lead to improvements in the quality of educational services.

The idea of making higher education “free” in Quebec is hardly new, but recently, some politicians have revived the debate by promising to implement such a policy if elected.(1) While this idea may seem attractive at first glance, it would be costly for Quebec taxpayers, would not necessarily lead to more students graduating, and would also be unfair.

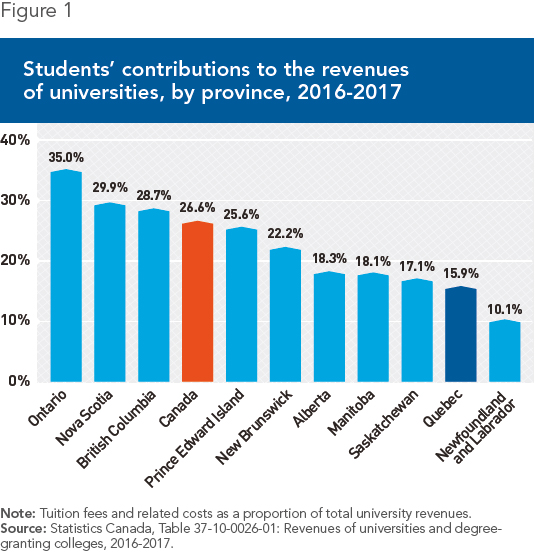

“Free” Tuition, Price Tag: $1.3 Billion

The very concept of “free” tuition is misleading. Since nothing is really free, what this really means is making taxpayers finance higher education, rather than the students who benefit directly from the service. Already, students’ financial contribution in the form of tuition fees and related costs, which amount to a little more than $3,700 per student per year of university,(2) represents just 16% of the revenues of Quebec universities. Direct subsidies granted by the various levels of government account for 62% of revenues, while the remainder comes from private sources or from abroad.(3) In Canada, only students in Newfoundland and Labrador contribute less proportionally to the financing of their studies (see Figure 1).

Including the college network, the Quebec government’s total spending on higher education amounts to a $5.6-billion annual bill for taxpayers;(4) making it “free” for students would substantially increase this total. The abolition of university and college tuition fees and related costs would mean an extra $1.1 billion a year if applied solely to Quebec students, and $1.3 billion if extended to Canadian and foreign students. The cost would be $162 million at the college level and $1.1 billion at university, supposing that the number of students remained constant.(5)

Free Tuition, Accessibility, and Graduation Rates

The central argument invoked by those who favour this policy is that it would considerably improve accessibility to higher education. In fact, this is a myth.

Students’ decision to attend an establishment of higher learning depends above all on their aptitudes, their interests, and their family and social environments.(6) These and other factors explain practically all of the gap between the enrolment rates of students from less privileged backgrounds and those from families that are better-off; financial constraints explain just 12% of this gap.(7)

Moreover, while the accessibility of higher education is important in itself, the decisive element in the analysis of educational policies remains graduation rates. Indeed, the benefit of education for society is not just to have students sit in classrooms, but rather to have educated, trained workers that have degrees in hand allowing them to put their knowledge to good use.

By this measure, the demonstration of a link between the cost for students and the accessibility of higher education is not established. Quebec is, after Newfoundland and Labrador, the province where tuition fees and related costs are the lowest, yet the percentage of individuals aged 25 to 34 who have a university degree is well below the Canadian average. In comparison, Ontario has proportionally more graduates than Quebec in this age bracket (68% versus 57%), even if its tuition and related costs are more than twice as high.(8)

Different factors, cultural or demographic for example, can explain the difference in the proportion of the population that pursues higher education. In Quebec, within the same educational system, francophones have a lower university graduation rate than their anglophone or allophone counterparts.(9)

As several economists have been saying for years, Quebec achieves good results when it comes to university attendance, but the higher education dropout rate remains high; in other words, we have many students, but not so many graduates. The issue is therefore not accessibility, but rather Quebec’s mediocre results when it comes to graduating students. Making higher learning “free” will not resolve this problem.(10)

Moreover, the student is the main beneficiary of his or her studies, with society receiving a far smaller benefit.(11) In Quebec, the median income of university graduates is around $79,000 a year, versus $42,000 for those with a high school diploma, and a little over $56,000 for workers with a college degree.(12) How could the government justify taking even more money from the 71% of Quebecers who do not have a university degree in order to pay a larger share of the total cost of the studies of those who will out-earn them in the future?(13)

Finally, one of the most significant arguments against the implementation of superficially free tuition is that the studies of less fortunate students are already financed by government: An undergraduate student whose parents earn less than $50,000 will receive $6,200 in financial assistance, including $3,650 of bursaries. Such a student will be able to pay nearly the entirety of his or her tuition fees and related costs just with these bursaries.(14)

Conclusion

Education is not free. The government devotes billions of dollars to it each year, ultimately paid for by taxpayers. The abolition of the various fees and costs that students must cover themselves would be expensive, ineffective, and unfair. It would also send the wrong message regarding the cost and value of higher education in a province that already undervalues it.

If fairness and the proper valuation of these studies is the goal, a better policy would be the adjustment of tuition fees as a function of the cost of different programs, accompanied by a corresponding adjustment in financial aid for students who need it.(15)

References

1. Patrice Bergeron, “Le Parti québécois mettra en place la gratuité scolaire pour le postsecondaire,” Huffington Post, May 27, 2018; Pascal Dugas Bourgon, “La candidate Marwah Rizqy veut persuader les libéraux d’adopter la gratuité scolaire,” Le Journal de Montréal, May 23, 2018; Samuel Rhéaume, “Christine Labrie a un nouveau poste au sein de QS,” La Tribune, August 5, 2018.

2. Statistics Canada, Table 37-10-0121-01: Canadian students, tuition and additional compulsory fees, by level of study, 2017-2018.

3. Statistics Canada, Table 37-10-0026-01: Revenues of universities and degree-granting colleges, Quebec, 2016-2017.

4. These are appropriations for the 2017-2018 fiscal year. Quebec Department of Finance, 2017-2018 Expenditure Budget: Estimates of the Departments and Bodies, March 2017, p. 91.

5. Authors’ calculations. This is the cost for the 2016-2017 year. The most recent data for the college sector are from 2012-2013. We therefore carried out a projection based on preceding years. Statistics Canada, op. cit., endnote 3; Quebec Department of Education and Higher Learning, Education Indicators, 2012, 2013, and 2014 Editions.

6. Michel Poitevin and Rui Castro, “Niveau et modulation des frais de scolarité,” in Marcelin Joanis and Claude Montmarquette (eds.), Le Québec économique 7 : Éducation et capital humain, CIRANO, December 19, 2017, p. 200.

7. This is for the enrolment gap between the 1st and 4th income quartiles. Marc Frenette, Why Are Youth from Lower-income Families Less Likely to Attend University? Evidence from Academic Abilities, Parental Influences, and Financial Constraints, Statistics Canada, February 2007, p. 21.

8. Statistics Canada, Table A.1.3: Percentage of the 25- to 64-year-old population that has attained tertiary education, by age group and sex, OECD, Canada, provinces and territories, 2016; Statistics Canada, op. cit., endnote 2.

9. Robert Lacroix and Louis Maheu, “Les tendances de la diplomation universitaire québécoise et le retard des francophones,” in Marcelin Joanis and Claude Montmarquette (eds.), op. cit., endnote 6. See also the interview with one of the authors of the study, Robert Lacroix in Hugo Pilon-Larose, “Formation préuniversitaire collégiale : des chercheurs contestent l’efficacité des cégeps,” La Presse, January 25, 2018.

10. Daphnée Dion-Viens, “Encore plus de décrocheurs dans les universités,” Le Journal de Montréal, February 1st, 2016.

11. The private benefit for the student is evaluated to be at least 60%, while society gets at most 40% of the total benefit associated with education. See Michel Poitevin and Rui Castro, op. cit., endnote 6, p. 185.

12. In companies of 200 employees or more. Institut de la statistique du Québec, Enquête sur la rémunération globale au Québec Collecte 2017, Rémunération globale et salaires, May 2018.

13. Statistics Canada, Education in Canada: Key results from the 2016 Census, November 29, 2017.

14. Based on a scenario in which the student has no other sources of income and on the tuition fees and related costs in 2017-2018. Government of Quebec, Department of Education and Higher Learning, Loans and Bursaries – Full-Time Studies, Assessment, Assessment Simulator, September 1, 2018 to August 31, 2019; Statistics Canada, op. cit., endnote 2.

15. On the adjustment of tuition fees as a function of the cost of programs and a global analysis of higher education in Quebec, see Michel Poitevin and Rui Castro, op. cit., endnote 6.