Poverty Is Not a Permanent State of Affairs in Canada

The fate of the poorest members of our society is rightly a recurring subject of concern in economic debates. Certain statements commonly heard can, however, give the impression that there are a lot of low-income people in Canada, and that for the majority of them, poverty is a permanent state. This perception is actually contrary to the observed facts. As we shall see, the results of the available research are clear: Social mobility is high in Canada. The proportion of low-income individuals who remain in this situation is very low, and the longer the time period analyzed, the more this proportion drops.

Media relase: Only 1.5% of Canadians live in poverty for extended periods of time

La pauvreté n'est pas une condition permanente : Economic note (in French) on poverty and social mobility (May 2001)

Links of interest

Links of interest

|

|

|

| Très peu de Canadiens restent pauvres longtemps (Le Journal de Montréal, September 23, 2015) | Interview (in French) with Youcef Msaid (Radio-Canada International, September 25, 2015) |

Poverty Is Not a Permanent State of Affairs in Canada

The fate of the poorest members of our society is rightly a recurring subject of concern in economic debates. Certain statements commonly heard can, however, give the impression that there are a lot of low-income people in Canada, and that for the majority of them, poverty is a permanent state. This perception is actually contrary to the observed facts. As we shall see, the results of the available research are clear: Social mobility is high in Canada. The proportion of low-income individuals who remain in this situation is very low, and the longer the time period analyzed, the more this proportion drops.

The Methodological Challenge

Judgments regarding the permanence of poverty are often based on a statistical illusion. To take an extreme case, in a society in which all 25-year-olds were poor but all 50-year-olds were rich, the statistical data would indicate that there are more or less the same proportion of poor people year after year. This could lead one to imagine that a portion of the population is living in perpetual poverty. Yet in fact, these poor individuals would be different people from one decade to the next, and no member of this society would be permanently poor.

We also have to consider the fact that having a low income when one is a young adult or in retirement does not necessarily imply a lack of goods and services. People are generally able to smooth out their consumption levels over time through the use of loans and savings in order to deal with income fluctuations that occur throughout their lives.(1)

Indeed, what we observe is that people are more likely to borrow when they’re young, in order to pay for studies or to buy a property, for example, and to save more as their incomes increase. Accumulated savings over the years allow one to build up one’s assets and maintain one’s standard of living in retirement when employment income falls.(2)

The statistics on the evolution of income distribution within the population as a whole therefore tell us very little about the progression of the living standards of the same people through time that is made possible by social mobility.

There are two kinds of research on social mobility that can shed some light on this situation. Intergenerational studies measure the influence of family income during an individual’s childhood on his or her income as an adult. In a mobile society, family income during childhood has little influence on the income that someone will earn later in life. Intragenerational studies, on the other hand, follow the changing incomes of the same individuals over a period of several years. There is social mobility if individuals’ relative positions on the income scale change over time.

Intergenerational Studies

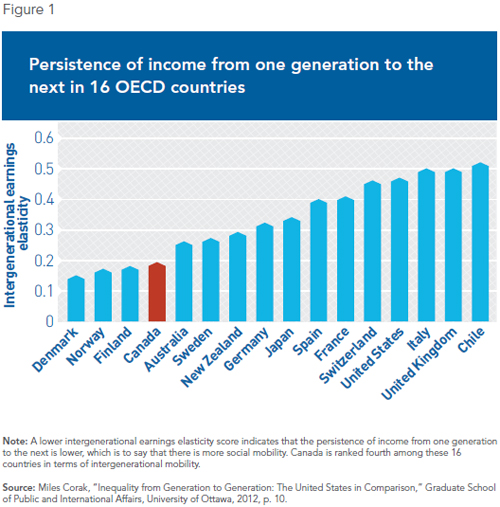

Ideally, everyone should have the opportunity, regardless of initial family situation, to develop his or her talents and to succeed economically. This aspect of social mobility is measured using an indicator called the intergenerational elasticity of earnings. In a society with high social mobility, we can expect to find an elasticity close to 0, whereas at the other extreme, in a society founded on caste privileges, for example, this elasticity would approach 1.

Figure 1 presents comparable estimates of the intergenerational earnings elasticity for 16 OECD countries for which data are available. Canada does very well with an elasticity of 0.2, ranking fourth among these countries in terms of intergenerational mobility. This means that only 20% of a family’s economic advantage (or disadvantage) persists into the next generation.(3) To take a concrete example, in a family with an income that is $10,000 below the average, the members of the following generation can expect to have incomes that are just $2,000 below average.

Intergenerational studies cover a relatively long period of time and contrast the fates of the members of specific families from one generation to the next. What about social mobility over a shorter time frame? Do low-income people remain in this situation for extended periods? How many of them do so? Intragenerational studies, which follow the same individuals over several years, provide some answers to these questions.

Intragenerational Studies

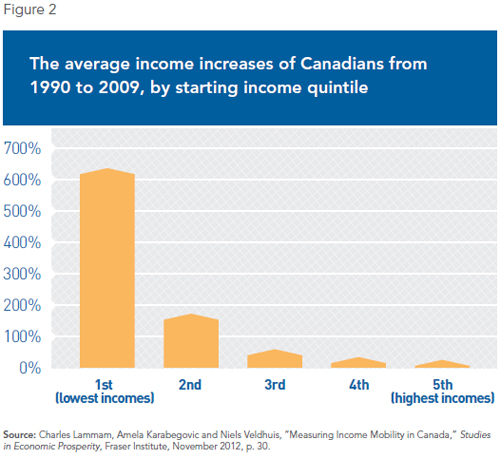

In Canada, it is possible to measure intragenerational mobility thanks to a database maintained by Statistics Canada. The most recent study using these data shows that Canadians at the bottom of the ladder generally do not remain there for long. Indeed, just 13% of individuals who were in the first income quintile in 1990 (the first quintile is made up of the 1/5 of the population with the lowest incomes) were still in that same quintile in 2009, while 21% had incomes that placed them in the second quintile, 24% in the third, and 21% in each of the top two quintiles.(4)

Research shows that the average annual income of those who found themselves in the lowest quintile in 1990 had grown from $6,000 to $44,100 in 2009 in constant dollars, an average increase of 635%. As for individuals who found themselves in the top quintile in 1990, their incomes grew by an average of 23% over this same period, from $77,200 to $94,900 (see Figure 2).

The members of the top income quintile earned on average 13 times the incomes of those in the bottom quintile in 1990, but by 2009, the incomes of the two groups (made up of the same individuals) were only separated by a factor of two.(5)

The Poor Are Getting Richer, Too

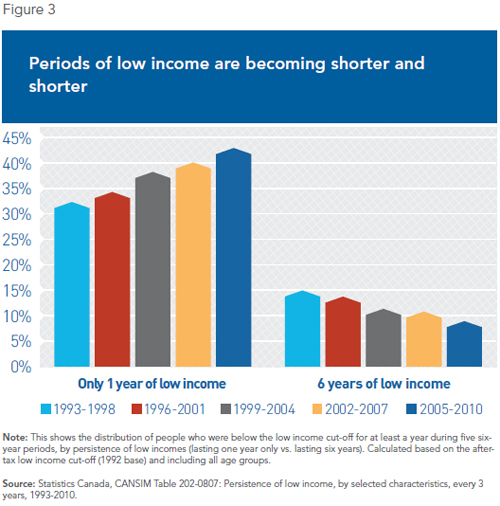

By using other Statistics Canada databases, it is possible to follow the evolution of the annual incomes of the same individuals for six-year periods. By comparing the results from 1993 to 2010, it becomes evident not only that the proportion of low-income individuals is falling,(6) but that these people remain in this situation for shorter and shorter periods of time.

Specifically, between 1993 and 1998, 25% of Canadians found themselves in a low-income situation for at least one year. However, from 2005 to 2010, this proportion had fallen to 17%,(7) which shows that there has been a marked improvement in the economic situation of people at the bottom of the income ladder.

Those who nonetheless do find themselves with low incomes remain in this situation for less time than they used to. Between the 1993-1998 and the 2005-2010 periods, the proportion of those who remained in this situation for just one year rose, from 32% to 43%, while the proportion having spent six years in this situation fell, from 15% to 9% (see Figure 3).

Measured against the population as a whole, we find that the phenomenon of the persistence of low incomes for several years only affects a small minority of Canadians. Indeed, only 3.6% of all Canadians remained below the low income cut-off for the six years of the 1993-1998 period, and this proportion had fallen to 1.5% for the 2005-2010 period.(8) This decrease in the persistence of low incomes is itself an indication that social mobility has grown over the years.

Conclusion

What matters more than socioeconomic position at any given moment is that those who find themselves at the bottom of the income ladder are unlikely to remain there long, that they are not prisoners of their status, and that their children are not condemned to remain there. This is precisely the situation of opportunity that prevails for just about all Canadians.

The available studies show that there is great social mobility in Canada, both from one generation to the next and within individuals’ own lives. People are constantly moving between income quintiles. Those who were at the bottom of the ladder 20 years ago have experienced, on average, extraordinary income growth.

The alarmist statements sometimes heard regarding the fact that poverty is a permanent condition for a substantial part of the population, and that “the rich get richer while the poor get poorer,” are therefore baseless.

This Economic Note was prepared by Yanick Labrie, Economist at the MEI, and Youcef Msaid, Associate Researcher at the MEI, in collaboration with Alexandre Moreau, Public Policy Analyst at the MEI.

References

1. See among others Patrick Villieu, Macroéconomie : consommation et épargne, Third Edition, La Découverte, 2008, pp. 42 and 43; Milton Friedman, A Theory of the Consumption Function, Princeton University Press, 1957; Orazio P. Attanasio and Martin Browning, “Consumption over the Life Cycle and the Business Cycle,” American Economic Review, Vol. 85, No. 5, 1995, pp. 1118-1137.

2. See Dirk Krueger and Fabrizio Perri, “Does Income Inequality Lead to Consumption Inequality? Evidence and Theory,” Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 73, No. 1, 2006, pp. 163-193.

3. Miles Corak, “Inequality from Generation to Generation: The United States in Comparison,” Graduate School of Public and International Affairs, University of Ottawa, 2012, p. 7.

4. Charles Lammam, Amela Karabegovic and Niels Veldhuis, “Measuring Income Mobility in Canada,” Studies in Economic Prosperity, Fraser Institute, November 2012, p. 27.

5. Ibid., p. 30.

6. The after-tax low income cut-off is defined by Statistics Canada starting from average household spending on food, shelter and clothing, namely 43% of disposable income. If a household devotes to these items a portion of its disposible income that is more than 20 percentage points above this average (namely, 63%), it is considered a low-income household. This threshold is adjusted as a function of household size and of the specific cost of living in the region. Statistics Canada, Low income cut-offs, May 2, 2013.

7. Statistics Canada, CANSIM Table 202-0807: Persistence of low income, by selected characteristics, every 3 years, 1993-2010.

8. For each period, the proportion of Canadians having remained in a low-income situation for at least one year is multiplied by the proportion of those who remained in this situation for the entire six years. For 1993-1998: 24.6% X 14.6% = 3.6%; for 2005-2010: 17.3% X 8.7% = 1.5%. (The figures in the text have been rounded.)