The Economic Costs of the Boreal Caribou Recovery Plan

Since the addition of the boreal caribou to the threatened species list, the Quebec government has made considerable efforts to protect its habitat by limiting forestry companies’ access to the public forest. No one denies the need to have in place conservation measures for protecting biodiversity, as long as they have concrete positive effects and that the associated costs are not out of proportion with the goals. When it comes to the boreal caribou, though, these two criteria are not necessarily respected.

Media release: 2,931 jobs and $367 million threatened in Quebec due to caribou recovery plan

Technical Annex (in French only)

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| Un caribou forestier protégé, 117 emplois perdus dans la région selon l’Institut économique de Montréal (Radio-Canada, August 19, 2015)

Le coût du caribou forestier (Le Soleil, August 23, 2015) |

Interview (in French) with Jasmin Guénette (L’heure de pointe, Radio-Canada, August 19, 2015)

Interview (in French) with Jasmin Guénette (Dutrizac, 98,5FM, August 20, 2015) Interview (in French) with Alexandre Moreau (Bonjour la Côte, Radio-Canada, August 20, 2015) Interview (in French) with Jasmin Guénette (Normandeau-Duhaime, FM93, August 21, 2015) |

Report (in French) with Jasmin Guénette (Radio-Canada, August 20, 2015)

Interview (in French) with Jasmin Guénette (LCN news network, August 20, 2015) |

The Economic Costs of the Boreal Caribou Recovery Plan

Since the addition of the boreal caribou to the threatened species list, the Quebec government has made considerable efforts to protect its habitat by limiting forestry companies’ access to the public forest.(1) The government’s actions, however, are not sufficient to meet the demands of environmentalist groups and the restrictions called for by certain governmental organizations.(2)

No one denies the need to have in place conservation measures for protecting biodiversity, as long as they have concrete positive effects and that the associated costs are not out of proportion with the goals. When it comes to the boreal caribou, though, these two criteria are not necessarily respected. Given the importance of the forestry sector for affected regions, it is vital that we analyze the economic repercussions that would be entailed by additional governmental constraints on logging operations.

Quebec’s Boreal Caribou Population

Over time, the boreal caribou’s range has steadily receded northward, a phenomenon that has been going on since the arrival of the first European settlers in the 17th century. Whereas it was formerly found in upstate New York, in Vermont, and in New Hampshire, today in the eastern part of the continent, the boreal caribou survives only in the boreal forests. Sport hunting and the transformation of its habitat appear to be the main causes of declining populations.(3)

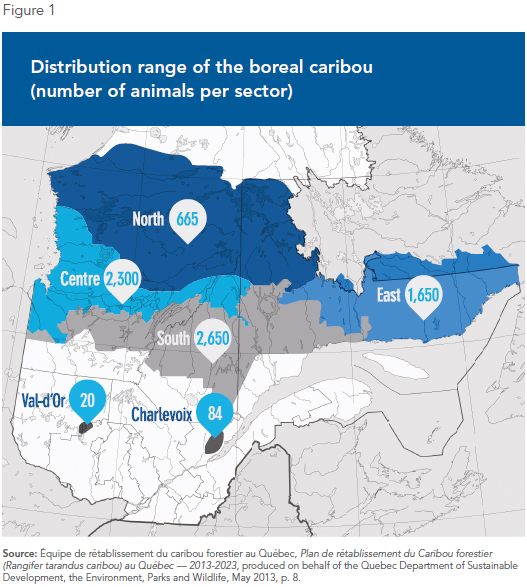

According to the latest estimates, Quebec’s boreal caribou population is just under 7,400 and is spread over five broad sectors covering a total surface area of 644,000 km2 (see Figure 1).

In the North sector, covering nearly 250,000 km2 where there is very little human activity, the 665 recorded boreal caribou share a good part of their territory with the migratory caribou, a kind of caribou located further to the north in Quebec.(4) Although genetically distinct, these two types of caribou are difficult to distinguish with the naked eye. Because hunting migratory caribou is permitted, it happens that boreal caribou are accidentally killed during the winter hunting season.(5)

In the Centre and East sectors, which cover a total surface area of 226,000 km2, human disruptions are also very limited and primarily involve mining activity and hydroelectric development. The population density in these sectors is among the highest in the distribution range, with an estimated 2,300 and 1,650 animals, respectively.

As for the South sector, which extends over a surface area of 165,000 km2 of boreal forest, this is where intensive commercial logging takes place. There are nonetheless 2,650 boreal caribou in this sector. Outside of the caribou’s contiguous range, there are also the two isolated populations of Val-d’Or and Charlevoix, whose numbers are estimated at 20 and 84 boreal caribou, respectively.(6) In all, over half of the boreal caribou population therefore roams in forests where no forestry activities take place.

The Boreal Caribou Recovery Plans

To counter the shrinking of its range, the government of Canada designated the boreal caribou a threatened species in 2003.(7) By law, the ministers in charge at the federal, provincial, and territorial levels have to prepare recovery programs in order to ensure the survival of the species.(8) This federal initiative was not without consequences for Quebec, insofar as the boreal caribou occupies a territory where commercial and touristic activities take place.

It is in this context that the Équipe de rétablissement du caribou forestier (the Boreal Caribou Recovery Team) was appointed by the Quebec government to study population dynamics and to ensure the coordination of habitat protection measures. A first recovery plan was produced for the 2005-2012 period, followed by a second plan for the 2013-2023 period whose starting date was however pushed back to 2018.(9) Whereas the first plan mainly targeted the protection of certain forests considered to be essential to the survival of the caribou, the second proposes an approach based on respecting a disturbance rate set at 35% of a given land area, as recommended by Environment Canada.(10) Ultimately, this latest plan aims to increase and to maintain Quebec’s boreal caribou population at 11,000 animals over the total extent of its current range.(11)

At this time, the restrictions in effect stem from the first plan and do not entail significant impacts on logging activities.(12) However, if the government goes forward with its intention to respect the second plan’s 35% disturbance rate, the restrictions will lead to losses of thousands of jobs, at a time when the sector is only just recovering from a crisis.

Forestry Regions Already in Trouble

Since the start of the new millennium, Quebec’s forestry regions have suffered from economic conditions that have not favoured the timber industry. The annual harvest fell by nearly 40% between 2000 and 2013.(13) As a result, a third of all jobs related to the forestry sector disappeared during this same period.(14) The number of processing plants has gone from about 580 to 351 over the past ten years.(15)

Despite this decline, forestry remains an important sector of economic activity in Quebec. In 2013, the forestry sector accounted for 60,082 jobs and its production was valued at $6.3 billion, or 2.1% of Quebec’s GDP.(16) In the Nord-du-Québec region, the forestry sector accounts for 43% of total employment and 26% of GDP. In the Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean region, where 22% of Quebec’s total lumber harvest comes from, the forestry sector accounts for 10% of total employment and 14% of GDP.(17) These resource-based regions are therefore very sensitive to variations in the lumber harvest.

Although investments and exports have picked up again since 2012,(18) this trend could be short-lived if the province’s second recovery plan is put into effect.

The Impact of Reducing the Allowable Cut

Respecting a disturbance rate of just 35% of the land area would reduce the allowable cut, which is to say the volume of lumber available to be logged each year, by approximately 3 million cubic metres.(19)

This reduction of the volume of available lumber would not necessarily entail an equivalent reduction in the lumber harvest, however. Indeed, in the economic situation that has prevailed since the start of the 2000s, the public forest has not been harvested to its full capacity. For the period from 2008 to 2013, the forestry harvest in the regions affected by the plan corresponded to just 79% of the total volumes allocated by the province’s top forest supervisor, on average. These unharvested volumes would absorb in part or in whole, depending on the region, the reductions of available volumes due to the protection of caribou habitat.(20)

By accounting for the volumes of unharvested lumber, we can estimate that the implementation of the second recovery plan would entail a potential drop in the harvest of 1.3 million m3 of lumber per year.(21) Given the regional distribution of caribou populations and of the volumes of unharvested lumber, only the Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean and the North Shore regions would experience job losses.

For the Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean region, we have estimated that 2,701 jobs would be lost, and that GDP would fall by $339 million. This is equivalent to 117 jobs lost per caribou saved, as well as an annual cost of $14.7 million per caribou saved. For the North Shore region, the cost would be lower (230 jobs and $29 million), but would still amount to 8 jobs sacrificed and $0.9 million per boreal caribou. The cost would be minimal in the other administrative regions located in the plan’s distribution range.

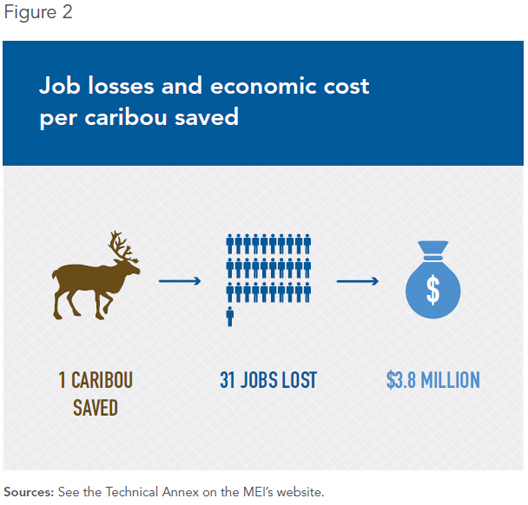

If the total cost for all regions (2,931 jobs and $367 million) is spread out over the number of caribou saved in forests under development, namely 96 per year, the loss is nonetheless 31 jobs per caribou saved, and $3.8 million per year (see Figure 2).

Uncertain Results

Although the imposition of these restrictions inevitably entails a drop in the allowable cut and in the volumes of lumber harvested, there exists a considerable level of uncertainty with regard to the evaluation and the achievement of the conservation targets.

The absence of a boreal caribou survey carried out in a systematic manner and the lack of precision in the evaluation methods mean that it is difficult to know the exact state of the populations. Indeed, only 30% of the caribou’s distribution range has been surveyed, and only 4% of the North sector.(22)

Even when surveys are carried out in a systematic fashion, it is difficult to explain the causes of population variations, which include the mobility of herds. For example, in 1999 and again in 2012, the Quebec Department of Natural Resources carried out population surveys in the Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean region, which for the first time allowed for a comparison of the state of the populations in time over a single area. The population more than doubled between the two surveys despite a high level of disturbance, from 115 to 247 animals, but it was not possible to draw any clear conclusions regarding the causes of this increase.(23)

Even if we completely ceased all logging in the caribou’s range of distribution, it is entirely possible that downward population trends would continue because of factors like climate change, forest fires, insect epidemics, and hunting.(24) In short, forestry activities are but one factor among many others.

Conclusion

Although the issue is complex, “the scientific study carried out by Environment Canada (2008, 2011) emphasizes that activities can occur within caribou habitat without threatening the species, as long as their cumulative effects do not destroy the biological and physical attributes necessary for its survival and recovery.”(25) Other studies have shown that the disturbance rate can reach 66% without threatening the caribou population.(26) The 35% target should thus not be considered an absolute limit.

It would therefore be relevant to take into account the socioeconomic impact of the boreal caribou recovery plans and to make sure that the costs are not out of proportion before imposing additional restrictions on forestry activities. The Species at Risk Act in fact requires that this aspect be considered.(27) And yet, to this day, no numerical analysis of costs has been made public, whether by the government or by environmentalist groups. Is it really reasonable to sacrifice on average 31 jobs and $3.8 million for the uncertain preservation of each caribou?

This Economic Note was prepared by Alexandre Moreau, Public Policy Analyst at the Montreal Economic Institute, and Jasmin Guénette, Vice President of the Montreal Economic Institute.

References

1. Équipe de rétablissement du caribou forestier au Québec, Bilan du plan de rétablissement du caribou forestier (Rangifer tarandus caribou) au Québec — 2005-2012, produced on behalf of the Quebec Department of Sustainable Development, the Environment, Parks and Wildlife, May 2013, p. v.

2. Alexandre Shields, “Une nouvelle stratégie édulcorée,” Le Devoir, May 28, 2015; Équipe de rétablissement du caribou forestier au Québec, Lignes directrices pour l’aménagement de l’habitat du caribou forestier (Rangifer tarandus caribou), produced on behalf of the Quebec Department of Sustainable Development, the Environment, Parks and Wildlife, May 2013.

3. Équipe de rétablissement du caribou forestier au Québec, Plan de rétablissement du Caribou forestier (Rangifer tarandus caribou) au Québec — 2013-2023, produced on behalf of the Quebec Department of Sustainable Development, the Environment, Parks and Wildlife, May 2013, pp. ix and 1.

4. Équipe de rétablissement du caribou forestier au Québec, op. cit., footnote 3, pp. 5 and 58.

5. Ibid., p. 52.

6. Ibid., pp. 5, 6, 16, and 58.

7. Decision made following the designation of the woodland caribou (boreal population) as a threatened species by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) in 2002. Government of Canada, Species at Risk Public Registry, Caribou Boreal population.

8. When the competent minister concludes that the recovery of the listed species is feasible, he or she must file a recovery plan within two years following the species being listed as threatened or extirpated. Government of Canada, Species at Risk Act, Sections 10, 40 to 42 and Schedule 1, December 2002.

9. Louis Tremblay, “Québec reporte le plan à 2018,” Le Quotidien, April 17, 2015.

10. The guidelines stemming from the 2005-2012 plan were revised following the filing of the new 2013-2023 plan. Équipe de rétablissement du caribou forestier au Québec, op. cit., footnote 2, pp. 2 and 9.

11. Quebec Department of Forests, Wildlife and Parks, Liste des espèces fauniques menacées ou vulnérables au Québec, Caribou des bois, écotype forestier.

12. According to our calculations, the reduction in volumes of wood available for harvest related to the application of the measures included in the 2005-2012 plan is offset by the fact that a portion of the available volumes at least equivalent to the reduction is not harvested in the affected regions. The measures are in effect from April 1st, 2015 to March 31, 2018. Direct communication with the Bureau du forestier en chef; Daniel Pelletier, Caribou et cerf de Virginie : leur prise en compte dans le calcul des possibilités forestières, Bureau du forestier en chef, December 3, 2014, p. 31.

13. From 42,155,000 m3 in 2000 to 26,119,000 m3 in 2013. Quebec Department of Forests, Wildlife and Parks, Direction du développement de l’industrie des produits du bois, Ressources et industries forestières : Portrait statistique édition 2015, 2015,p. vii; Quebec Department of Forests, Wildlife and Parks, Direction du développement de l’industrie des produits du bois, Ressources et industries forestières : Portrait statistique édition 2004, 2005, p. 05.02.01.

14. Quebec Department of Forests, Wildlife and Parks, Importance des ressources naturelles dans l’économie québécoise, emplois, May 2014.

15. Quebec Department of Forests, Wildlife and Parks, “Enquête sur les pertes d’emplois dans l’industrie de transformation du bois et du papier,” May 15, 2015, p. 2. This refers to the number of processing plants with a lumber processing permit that use more than 2,000 m3 of lumber per year. Data supplied by the Quebec Department of Forests, Wildlife and Parks, Direction du développement de l’industrie des produits du bois, Registre forestier.

16. Chained 2007 dollars. Quebec Department of Forests, Wildlife and Parks, Importance des ressources naturelles dans l’économie québécoise, emplois et PIB, May 2014.

17. Authors’ calculations. See the Technical Annex on the MEI’s website.

18. Bureau du forestier en chef, Bilan de l’état de santé des forêts publiques : un aménagement durable pour des forêts en santé, Mise en valeur des ressources, May 2, 2015.

19. Quebec Forest Industry Council, “La certification forestière FSC doit tenir compte de l’équilibre entre l’environnement, la société et l’économie,” Press release, February 12, 2014; Louis Tremblay, “Caribou forestier : en dessous du cheptel actuel,” Le Quotidien, May 23, 2015.

20. We must also take into account the fact that the harvest of nearly 70% of these volumes would impose additional operational constraints, because the forest is not sufficiently dense, the diameter of the trees is too small, or the trees are located on steep slopes. Bureau du forestier en chef, “Volumes non récoltés de la période 2008-2013 potentiellement disponibles à la récolte pour la période 2013-2018 : Détermination finale pour l’ensemble des unités d’aménagement,” Décision du forestier en chef, September 25, 2014, pp. 6-8; Bureau du forestier en chef, Récolte dans les contraintes opérationnelles : Suivi de la recommandation du Forestier en chef de 2006, Avis du Forestier en chef au ministre des Forêts, de la Faune et des Parcs (FEC-AVIS-2014-02), June 25, 2014, pp. 9, 10, and 13.

21. Authors’ calculations. See the Technical Annex.

22. Équipe de rétablissement du caribou forestier au Québec, op. cit., footnote 3, p. 15.

23. Department of Natural Resources, Direction de l’expertise du Saguenay—Lac-Saint-Jean, Inventaire du caribou forestier (Rangifer tanradus) à l’hiver 2012 au Saguenay—Lac-Saint-Jean, February 2013, p. 17.

24. Elston Dzus et al., Caribou and the National Boreal Standard: Report of the FSC Canada Science Panel, prepared for the Forest Stewardship Council, July 26, 2010, pp. 18-23.

25. Équipe de rétablissement du caribou forestier au Québec, op. cit., footnote 3, p. 29.

26. Ibid.

27. Government of Canada, op. cit., footnote 8, preamble.