Lowering fees does not make universities more accessible – Quebec’s enrolment rates are slipping in spite of the lowest fees in Canada

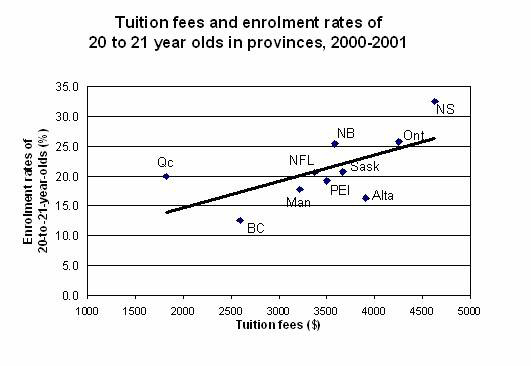

The debate over university tuition fees in Quebec is a false one, and those who say higher fees would reduce accessibility to university are wrong. Data from across Canada reveal low tuition fees do not mean high enrolments; in fact, the contrary is true. The graph illustrates this paradox. The higher the fees, the higher the enrolment rate tends to be.

In 2003-04, average undergraduate tuition fees in Quebec were $1,862 a year, the lowest in Canada and more than $2,000 less than the Canadian average of $4,025.

But Quebec has one of Canada’s lower university enrolment rates, with just 20 per cent of its 20-to-21-year-olds registered full time at university in 2000. On the other hand, Nova Scotia, which has the highest tuition fees at $5,557, also had the highest enrolment rate at 32.6 per cent.

University enrolment rates have actually declined slightly in Quebec in spite of the tuition freeze that has been in effect since 1994, while enrolments in Ontario have increased, despite major tuition fee increases that brought fees this year to $4,923.

As for related costs, the subject of much recent discussion, it should be noted, even if they are slightly higher in Quebec than elsewhere in Canada ($685 in Quebec in 2003-04, vs. a Canadian average of $623), this modest difference in no way changes the general picture.

Thus, nothing guarantees a freeze or even a drop in tuition fees would guarantee greater future access to higher studies. Nor do low tuition fees necessarily benefit the least wealthy students. Figures from Statistics Canada show 83 per cent of young people whose parents’ employment income is at least $80,000 are likely to pursue post-secondary studies. For families with incomes below $30,000, that figure is only 53 per cent.

Inability to pay does not necessarily explain these differences. Even if higher education were free, young people from underprivileged and less educated backgrounds would still be less inclined to go to university for all sorts of other reasons. Research on this matter has identified a number of factors, in particular parents’ educational levels and occupations, students’ high school grades, parents’ expectations and savings levels of students or parents.

Statistics Canada surveys found only 26 per cent of Canadian students who did not move on to post-secondary studies give financial reasons as the main cause. Nineteen per cent mentioned a desire to take a pause in their studies, while nine per cent expressed a lack of interest in more education.

Among those who quit a post-secondary program, only nine per cent gave financial reasons as their main reason for dropping out. In Quebec, that number was 13 per cent, while 17 per cent mentioned a lack of interest.

Another issue is the individual responsibility of the students. University graduates typically have incomes well above average, ample reward for their higher short-term costs. Education is a very profitable investment in human capital. It seems only normal those who benefit from it should carry a substantial part of the costs. In general terms, the average income of university graduates is about 60 per cent above the overall average, and unemployment among graduates is about 40 per cent less than that of the labour force in general.

In subsidizing higher education across the board by maintaining low tuition fees, middle-income taxpayers are in effect subsidizing young people from wealthy families and the higher salary-earners of tomorrow. A more effective way of ensuring widespread access to higher studies would be to offer financial assistance directly, through better targeted loans and grants.

The real debate should focus on how to build and consolidate a university network that meets the needs of varied clienteles, with some institutions responding to specific regional requirements and others emphasizing teaching and research of a national or international calibre. Universities should have the option of charging additional fees based on the mandate and mission they set for themselves.

We know universities here suffer from major gaps in terms of libraries, laboratories and computer equipment, and that they have difficulty recruiting and retaining the best professors. Robert Lacroix, rector of the Université de Montréal, reminded us recently ”in the other Canadian provinces, classrooms are renovated, laboratories are well equipped and libraries are well stocked.”

Philip Merrigan, head of the economics department at UQÀM, stated ”there exists no doubt that current underfinancing is harming quality.” At the end of the road, what does it matter if everyone can attend university if the diplomas they receive are worthless?

The Quebec government faces many pressures in the allocation of limited resources, particularly with rapid growth in health-care costs. It seems evident it will be unable to continue financing university operations adequately if the tuition-fee freeze is maintained. A refusal to allow universities to fulfill their financial requirements risks compromising the quality of higher education in Quebec without benefiting the young people who want access to it.

Norma Kozhaya is an economist at the MEI.