Time for Targeted Federal Coronavirus Stimulus

Viewpoint showing that targeted tax holidays provide rapid and effective assistance to affected workers and companies

As COVID-19 continues to spread across Canada, a rising chorus is calling for expensive fiscal stimulus to fight its economic fallout. This MEI publication asserts that given already low interest rates, fiscal measures are the textbook response.

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| It’s time for targeted federal stimulus (Sun Media, March 18, 2020)

Trois mesures fiscales pour contrer la COVID-19 (La Presse+, March 18, 2020) |

Interview (in French) with Luc Vallée (Politiquement incorrect – Richard Martineau, QUB Radio, March 17, 2020) |

This Viewpoint was prepared by Peter St. Onge, Senior Economist at the MEI, in collaboration with Luc Vallée, Chief Operating Officer & Chief Economist at the MEI. The MEI’s Taxation Series aims to shine a light on the fiscal policies of governments and to study their effect on economic growth and the standard of living of citizens.

As COVID-19 continues to spread across Canada, a rising chorus is calling for expensive fiscal stimulus to fight its economic fallout.(1) Given that interest rates are already very accommodating, fiscal measures, either tax relief or new spending, are the textbook response.

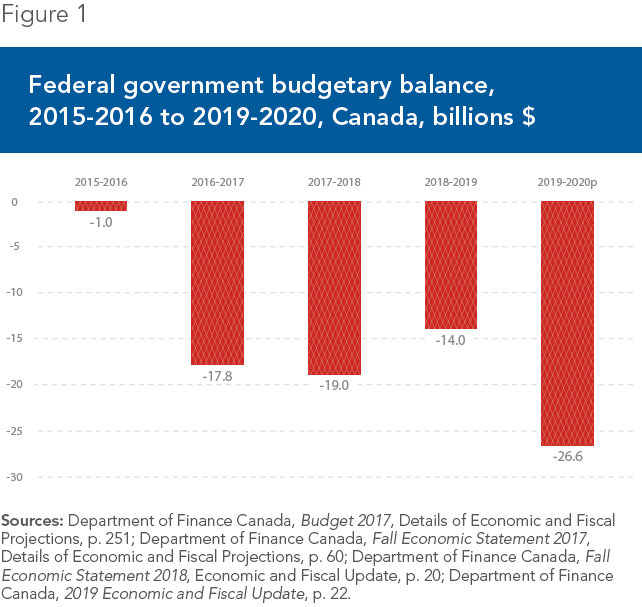

However, given Ottawa’s failure to set money aside while the economy was doing well(2) (see Figure 1), Canada can ill afford a scattershot approach. Rather, aid needs to target the specific threat: job losses and bankruptcies among workers and employers without the financial cushion to weather the storm.(3) Moreover, aid needs to move quickly—so forget about years-long highway construction.(4)

The Proper Diagnosis

In determining what help to bring to those who need it, we first want a clear picture of the actual threat. Economically, what sets this situation apart from a typical slowdown is its speed(5) and its specificity. In a “normal” recession, many sectors sink together. Coronavirus, in contrast, will likely have limited impact on some sectors, while it will devastate others as customers stay home to minimize contagion.

That means restaurants and food services, nightlife, accommodation and tourism, transport, and retail in general will be hit harder. These sectors are characterized by the presence of both small businesses and vulnerable workers, accounting for one in four private-sector jobs in Canada.(6) Because pay in food services and accommodation averages just $16.54 per hour, while wholesale and retail averages just $21.37 per hour,(7) it’s easy to see that many of these workers have no financial cushion for unexpected events.

The same is true for the businesses that employ them. Of the 119,000 restaurants and commercial accommodations in Canada, 98% are classified as small businesses.(8) Given fixed costs—rent, utilities, property taxes, licence fees—many simply don’t have the means to ride out a drop in sales lasting weeks or months.

Targeted Assistance

What are the possible options? First, Canada already has a purpose-built mechanism for such situations: Employment Insurance (EI). Ottawa could therefore decide to lower eligibility thresholds, raise payments, and extend the period of benefits.(9)

There is, however, a more effective way to help both workers and small business: tax relief, which has the advantage of being fast and easy to target. Just the thing for a jobs crisis affecting small service businesses is a payroll tax holiday for employers.

Currently, roughly 15% of salary is paid in taxes of all kinds, including the Canada Pension Plan (in Quebec, the QPP), EI itself, and other programs.(10) Half of this is paid by workers and half by employers—the self-employed pay both halves. A tax holiday would thus very quickly give companies an incentive to keep workers on, while putting extra money in workers’ pockets. Relief would especially help the self-employed who work part-time or for low wages.

A second form of fast and targeted stimulus could come from local governments in the form of a tax holiday for small business, by exempting them from the commercial property tax. The restaurant, nightlife, and retail industries are exactly the businesses that pay this tax, at punitive rates reaching, in Montreal, four times the residential tax rate.(11) Forgiving these taxes, or at least deferring them, can quickly help affected small businesses.

A third measure to implement, if the crisis endures, is a tax holiday on the GST and provincial sales taxes. GST receipts alone totalled over $3 billion per month last year.(12) Suspending it would offer a large stimulus, which would once again be quickly distributed with minimal administrative burden, considering the amounts involved. Moreover, by encouraging customers to spend, the measure precisely addresses the root cause of the economic crisis.

Favouring Speed and Impact

All three of these tax measures share the characteristic that they are prudent even without a crisis. Studies have found that every dollar of tax reduction is associated with two to three times more economic growth.(13) Furthermore, the stimulative effects of tax relief make it a better choice than lump-sum handouts that are, in practice, overwhelmingly converted into savings.(14) The speed with which it can be implemented also makes it a better choice than large infrastructure projects that can take years to get started. Finally, the targeted nature of tax relief makes it a prudent choice in this age of recurring deficits.

The Bank of Canada has already eased access to credit by lowering rates, compensating for higher credit spreads that come with economic risk. Government may have to revisit credit conditions if they were to tighten significantly, for the airline industry, for example, long hemmed in by government edicts and now hit by an existential crisis they did not cause. If needed, government could reprise the role of “lender of last resort” to small business it took after the 2008 financial crisis.(15) For speed and impact, though, the ball is clearly in the fiscal court.

References

- Theophilos Argitis, Erik Hertzberg, and Shelly Hagan, “Ball is in Trudeau’s court after the Bank of Canada’s rate cut,” BNN Bloomberg, March 4, 2020.

- Department of Finance Canada, Investing in the Middle Class – Budget 2019, March 19, 2019, p. 18.

- Aysegül Sahin et al., “Why Small Businesses Were Hit Harder by the Recent Recession,” Current issues in economics and finance, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Vol. 17, No. 4, July 19, 2011.

- Canadian Consulting Engineer, “Delays with Infrastructure Construction Projects,” June 24, 2015; Michael Fenn et al., Moving Canada’s Economic Infrastructure Forward: Addressing Six Risks to Timely, Economical, and Prudent Project Selection and Delivery, Discussion Paper, Lawrence National Centre for Policy and Management, Ivey Business School, January 2019.

- Stéphanie Grammond, “Un marché baissier en accéléré,” La Presse+, March 13, 2020.

- This represents over four million workers in all. Statistics Canada, The Daily, Table 2 − Employment by class of worker and industry, seasonally adjusted, page updated March 6, 2020.

- Statistics Canada, Employee wages by industry, annual, page updated March 15, 2020.

- Competition Bureau of Canada, Summary – Canadian Industry Statistics, page updated February 19, 2020.

- Employment and Social Development Canada, EI regular benefits, page updated January 7, 2020.

- Not including personal income tax collected from workers. Canada Revenue Agency, Canada Revenue Agency announces maximum pensionable earnings for 2020, page updated November 1st, 2019; Payworks, Payroll legislation, CPP & EI Deductions, page consulted March 15, 2020.

- Josef Filipowicz and Steven Globerman, Who Bears the Burden of Property Taxes in Canada’s Largest Metropolitan Areas? Fraser Institute, October 17, 2019, p. 12.

- Department of Finance Canada, Annual Financial Report of the Government of Canada Fiscal Year 2018–2019, page updated November 20, 2019.

- Christina D. Romer and David H. Romer, “The Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Changes: Estimates Based on a New Measure of Fiscal Shocks,“ American Economic Review, Vol. 100, No. 3, June 2, 2010.

- Gerald Prante, “Did the 2001 Tax Rebate Checks Stimulate Consumption? The Economic Evidence,” January 21, 2008; Donna Zerwitz, “Did the 2008 Tax Rebates Stimulate Spending?” The National Bureau of Economic Research, March 15, 2020.

- Business Development Bank of Canada, “BDC increased financing for entrepreneurs by 53% during financial crisis,” Press release, August 19, 2010.