GAFA Tax: A Bad Solution to a Nonexistent Problem

Economic Note showing that digital companies are already heavily taxed, and that this surtax would harm Canada’s digital economy and the Canadian population as a whole

The federal government’s bill to impose a surtax on the revenues of digital companies would hurt Canadian consumers according this MEI publication. “No matter how the government dresses up its digital tax bill, it is Canadian consumers who will once again pay for it,” said Olivier Rancourt, Economist at the MEI and author of the publication.

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| La taxe numérique coûtera plus de 1,1 G$ par année aux Canadiens (Le Journal de Montréal, October 20, 2022)

Liberal plan to tax tech giants will cost consumers billions, says new report (True North, October 20, 2022) Consumers will foot the bill for digital services tax (Sun Media Papers, October 28, 2022) |

Interview (in French) with Olivier Rancourt (Midi Pile, KYK Radio, October 20, 2022)

Interview (in French) with Olivier Rancourt (Trudeau-Landry, FM 93, October 20, 2022) |

This Economic Note was prepared by Olivier Rancourt, Economist at the MEI. The MEI’s Taxation Series aims to shine a light on the fiscal policies of governments and to study their effect on economic growth and the standard of living of citizens.

Few companies get people worked up as much as the tech giants, sometimes referred to as the GAFA (Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple) or GAFAM (if Microsoft is included) companies. Mostly, it is their profits that are criticized. Indeed, even though “making the rich pay” is not sound economic policy,(1) certain countries are trying to rebalance their budgets and cover the costs of electoral promises by increasing taxes on digital companies.

Along these lines, the government of Canada has announced its intention to impose a surtax on digital companies(2) starting in 2024. Inspired among other things by a similar measure in France,(3) the tax, commonly called the “GAFA tax,” would be a 3% surtax on the revenues of digital companies. This proposal has already been criticized,(4) and new information regarding this bill shows just how bad it would be for Canada. For one thing, this idea is based on a falsehood according to which these companies are not paying their “fair share.” For another, it will simply end up hurting the Canadian economy by taking the place of other reforms that could instead help our economy.

From “Level the Playing Field” to “They Don’t Pay Their Fair Share”

A lot of ink has already been spilled in Canada over the past decade on the debate regarding the taxation of digital companies. It started with discussion about implementing a “Netflix Tax” to force that company to collect sales taxes on digital goods.(5) The discussion took hold in the public debate following the 2015 federal election campaign. At the time, the Conservative Party, the Liberal Party, and the New Democratic Party had all come out against the application of this tax.

This multi-party promise had the effect of maintaining distinct taxation for digital companies, while the debate increasingly shifted to the idea of establishing a common fiscal framework for them and for “traditional” non-digital businesses, though with different means of getting there. While some suggested reducing the tax burden for all,(6) the federal government finally decided to force digital companies to collect the GST in 2021.(7)

The Trudeau government pressed on with a proposed digital services tax (DST) corresponding to 3% of the gross revenue of companies with total annual revenue of 750 million euros and Canadian revenue of over $20 million a year. The revenue targeted is that from online marketplace and advertising services as well as from social media services and user data.(8)

The DST was proposed as an interim measure while waiting for a multilateral agreement for the “acceptable” taxation of multinationals, including the GAFA companies.(9) This agreement, led by certain OECD countries, aims to respond to criticisms that certain multinational companies do not pay enough taxes in the countries where they generate profits.(10) The goal of this agreement is therefore to put an end to tax competition between countries and to force multinationals with sales of over 750 million euros to pay a minimum tax of 15% in the countries where they do business.(11)

The DST would remain in place up until the application of the international agreement. The federal government has declared its support of this agreement and its wish to put an end to the fiscal “race to the bottom” and force large corporations to pay their “fair share.”(12)

A Solution to a Nonexistent Problem

The first problem with the DST is that the premises upon which it is based are false. Looking at the investments of digital businesses in the Canadian economy and the agreements concluded with them, it is difficult to argue in good faith that they do not pay their “fair share.” Aside from the impossibility of calculating what constitutes a “fair share,” the average tax rate of GAFA companies over 5 and 10 years is higher than that of the other large corporations that make up Canada’s TSX 30 and TSX 60.(13) The large digital companies therefore pay more than their so-called “fair share.”

Not only do they pay more than other companies, but the effective tax rate of the GAFA companies is already higher than the 15% rate proposed by the agreement. Whether over a period of 5 or 10 years, their effective tax rate is 24%.(14) The DST would therefore add on a tax to hit a target that has already been reached.

Moreover, for a decade now, the fiscal and regulatory burden applied to digital and “traditional” companies in Canada has been standardized, so there is no good reason to impose a surtax on the GAFA companies.

Yet the DST arbitrarily penalizes digital companies, which are generally foreign-owned, since they have had more success over the past decade. This tax would in fact simply harm Canada’s digital economy, which the different governments otherwise want to stimulate.

A Harmful Tax for the Digital Economy and Its Users

What occurred in France after the introduction of a similar tax points to certain problems that the DST would give rise to in Canada.

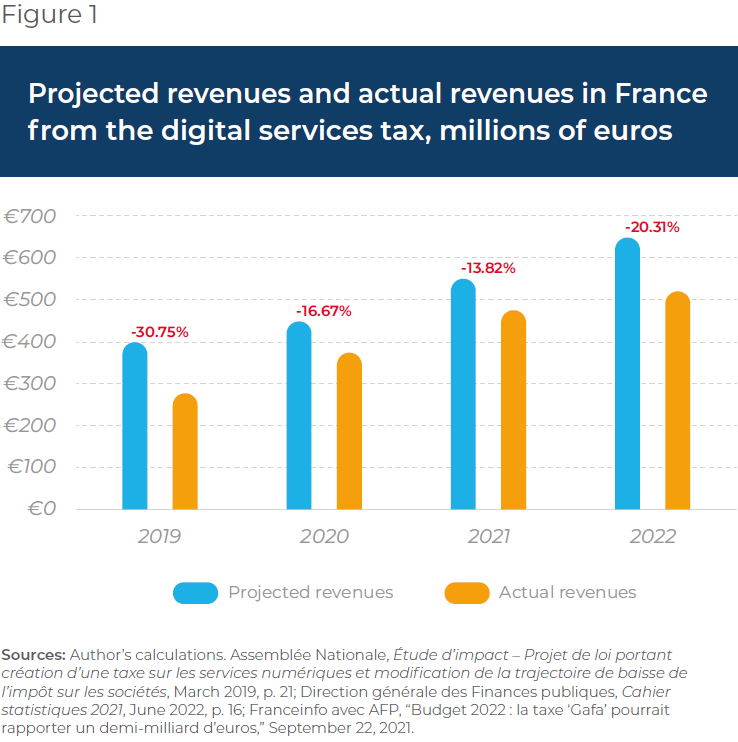

First of all, if the federal government’s goal is primarily to fill its coffers, it must be noted that one of the problems with the tax in France was an overestimation of its revenues (see Figure 1). Indeed, each year since the implementation of the tax, these have been lower than projected, by as much as 30%. The Canadian government estimates that it can collect $3.4 billion with this tax over five years.(15) The French experience suggests that the actual revenues could be much lower.

This loss of revenue is low, however, compared to the economic loss the DST would cause. To estimate this, it is necessary to observe the repercussions of similar taxes in Europe, and especially in France since this tax is modelled after the French tax. Once the GAFA tax was put in place in France, prices went up by 2% for clients of Google and by 3% for clients of Apple and Amazon.(16)

It is important to understand that the direct clients of digital companies are Canadian companies and individuals, whose bills will suddenly go up. Even for free platforms, the tax is passed on to companies that pay for advertising, and then onto their own customers, namely the entire Canadian population.

It is possible to calculate the economic loss and the excess cost resulting from the DST. It must be noted, however, that the calculation of this loss will not include the reduction in economic activity due to the weaker creative destruction and the diminished innovation in sectors of the Canadian economy that would result. The real economic consequences would be greater in the long term, as the measure would penalize innovation within digital companies by reducing the marginal profit of any investment.

Table 1 provides an estimate of the impact of price increases for consumers once the DST would be in place, under three scenarios. The three scenarios represent 33%, 66%, and 100% of the tax being passed on to consumers, corresponding to price increases of 1%, 2%, and 3% respectively. The amount comes from an estimate of the added value of the digital industry in Canada, which includes e-commerce, products delivered digitally, software, and support services.(17) This estimate takes into account neither the loss of investment and of productivity related to this drop in profits, nor the drop in demand for services related to this price increase.

If the price increase followed that of Google in France, it would be equivalent to over $2 billion a year for Canada’s digital economy.(18) Even under an optimistic scenario in which only 33% of the tax is passed on to consumers, it would still represent a loss of over one billion dollars a year. If we consider a price increase similar to Apple’s or Amazon’s in France, with the tax entirely passed on to consumers, the loss would then be close to $3.3 billion a year, even before considering the losses in investment and productivity which will in turn affect all economic sectors. These costs for Canadian consumers would thus be nearly equivalent to the hoped-for revenues from the tax over five years, namely $3.4 billion.(19)

Although these losses for the rest of the Canadian economy, beyond the digital sector, may be more difficult to quantify, they will be very real, pushing the prices of most goods and services higher. The DST thus risks coming into effect just as we are in the throes of renewed inflation at levels we have not seen for several decades. We see here again a hallmark of taxation: It is consumers who pay for tax hikes.(20)

Finally, as in France, it is very likely that Canadian companies will find themselves affected by the DST and be punished for their success. In France, the tax was applied to companies on the cutting edge of the digital economy like Criteo and Leboncoin.(21)

Statistics Canada estimated in 2021 that Canadian companies brought in $398 billion from online sales.(22) On average, large Canadian companies declared $79 million in gross revenues from e-commerce, which is much higher than the DST threshold of $20 million in Canada. This figure, moreover, does not include online advertising services, social media services, or user data, which are the other sectors targeted by the DST. It would be counterproductive to want to overtax our Canadian digital “champions,” who will certainly find it more difficult to pass the bill along to their own customers than the GAFA companies will.

The digital economy, we must not forget, is a source of innovation for the Canadian economy. It is a major source of creative destruction, and it is important to remember the gains that it generates. Even though traditional companies in Canada lose market share and revenues when digital companies arrive on the market and start competing with them, business customers and final consumers have access to a better service. Canada as a whole comes out ahead. An excellent example of this complex relationship is advertising: An ad on Google or Facebook can target a specific audience much more effectively than traditional media can.(23)

There Is No Need for a DST

In short, the introduction of a DST would not be good for Canadians. It would entail direct costs of over $2 billion for the Canadian economy, in addition to a significant increase in the cost of all future investment in the digital economy in Canada. This tax is not justified by the facts of the matter, since digital companies are already taxed as heavily as other large corporations, if not more so.

Even if the international tax agreement is not implemented by 2024, there is no reason for the DST. The high costs for Canadian companies and the Canadian population are not justifiable, with or without an agreement. The threat that is weighing on Canadian companies must be removed as soon as possible to reduce the uncertainty that is undermining Canadian innovation.

If the government wants to improve the competitiveness of traditional companies, it would be better to reduce their regulatory burden, as has been suggested before.(24) This would reduce the negative effects of taxes and regulations on the Canadian economy, in addition to increasing the international competitiveness of Canadian companies and stimulating innovation and economic growth.

It makes sense to want to ensure that Canadian companies and multinationals operate under a common fiscal and regulatory framework. However, this desire must not serve to justify protectionist measures or to increase the weight of regulation or taxation on Canadians. The proposed DST will only hurt Canadians, and will not resolve nonexistent problems.

References

- Valentin Petkantchin and Nathalie Elgrably-Lévy, Choking Hazard: The Adverse Effects of “Eat the Rich” Policies, MEI, Research Paper, September 2022, p. 7.

- Ici Radio-Canada, “Ottawa va taxer les GAFA, mais seulement à compter de 2024,” Ici Radio-Canada, January 1st, 2022.

- Louis Blouin, “Ottawa veut forcer les géants du web à percevoir la TPS dans ‘les prochains mois’,” Ici Radio-Canada, December 11, 2019.

- Nicolas Marques, Peter St. Onge, and Gaël Campan, Taxing the Tech Giants – Why Canada Should Not Follow the French Example, MEI, Research Paper, January 2020, p. 9.

- Chris Hall, “Why are politicians still terrified of taxing Netflix?” CBC News, May 16, 2019.

- Mathieu Bédard, “Netflix : régler le problème d’équité en réduisant le fardeau fiscal,” Huffington Post, October 5, 2017.

- David Friend, “Netflix adding GST/HST to Canadians’ bills starting Canada Day,” Global News, June 2, 2021.

- Department of Finance Canada, Digital Services Tax Act, February 14, 2022.

- Idem.

- Ali Bekhtaoui, “Entente entre 136 pays sur un taux fixé à 15 %,” La Presse, October 8, 2021.

- OECD, “Statement on a Two-Pillar Solution to Address the Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy,” October 8, 2021.

- Agence France-Presse, “Taxation des multinationales : accord à 136 pays avec un taux fixé à 15 %,” Ici Radio-Canada, October 8, 2021.

- Nicolas Marques, Peter St. Onge, and Gaël Campan, op. cit., endnote 4, pp. 17-18.

- Ibid., p. 16.

- Mélanie Meloche-Holubowski, “Plus de taxes… pour les plus riches,” Ici Radio-Canada, April 19, 2021.

- Nicolas Jaimes, “Google répercute la taxe Gafa sur ses tarifs en France,” Journal du Net, March 3, 2021.

- Statistics Canada, “Measuring digital economic activities in Canada, 2010 to 2017,” The Daily, May 3, 2019, p. 4.

- Author’s calculations. Ibid.

- Mélanie Meloche-Holubowski, op. cit., endnote 15.

- Valentin Petkantchin and Nathalie Elgrably-Lévy, op. cit., endnote 1, p. 38.

- Le Figaro et AFP agence, “La taxe Gafa concerne 26 entreprises en France,” March 20, 2019.

- Statistics Canada, “Digital technology and Internet use, 2021,” The Daily, September 13, 2022.

- Thomas Urbain, “Comment Netflix et Disney vont chambouler le monde de la publicité,” La Presse, September 25, 2022.

- Michel Kelly-Gagnon, “Should Netflix Be Regulated as a Traditional Canadian Broadcaster?” Huffington Post, September 12, 2014; Michel Kelly- Gagnon, “Taxing Netflix Is Not the Only Way to Level the Digital Playing Field,” Huffington Post, March 17, 2015.