Ending the Lockdown Depression

Viewpoint on the enormous costs of lockdowns, particularly with regard to job losses and public finances

Lockdown measures were put in place hastily and, apparently, without considering their economic and social costs. In this publication, researchers attempt to quantify the impact of lockdown measures.

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| Interview with Peter St. Onge (CTV News Montreal 12:30PM, CFCF-TV, July 6, 2020) |

This Viewpoint was prepared by Peter St. Onge, Senior Fellow at the MEI, in collaboration with Gaël Campan, Senior Economist at the MEI. The MEI’s Taxation Series aims to shine a light on the fiscal policies of governments and to study their effect on economic growth and the standard of living of citizens.

According to Statistics Canada jobs data, Quebec is already starting to recover from the “lockdown depression” much faster than the rest of Canada. The May jobs report was a contrast between policy-makers bringing blue-collar industries back to life quickly, and those going too slowly.

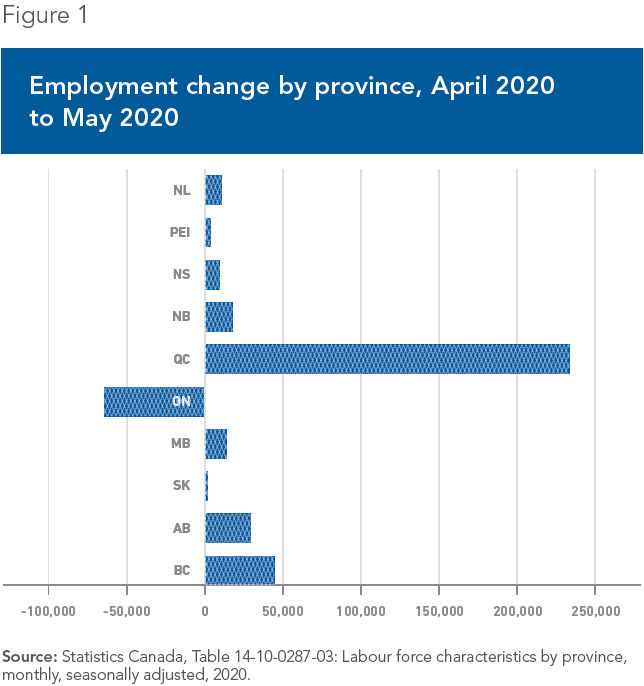

Last month, Quebec gained 230,900 jobs, accounting for 8 in 10 net jobs created across Canada (see Figure 1). The rest of the country managed an anemic 58,700 net jobs, with Ontario actually losing 64,500 jobs as its government kept the economy largely closed.(1)

This tale of two economies highlights that the epic job losses experienced since March are almost entirely due to the economic lockdowns, not to COVID-19 itself. In fact, increases in unemployment rates in countries that did not lock down, such as Sweden and Japan, have been far smaller than here in Canada.(2)

The enormous costs of lockdowns keep piling up. In addition to sky-high unemployment, government deficits have exploded—not to mention bankruptcies, drained savings, and suicides, though these are harder to quantify.

It was legitimate, and indeed important, for policy-makers to implement strong measures to try to save lives, but there were less economically harmful ways to do just that, such as measures focused on the elderly and more targeted lockdowns.(3) What’s done is done, and the idea is not to dwell on the past, but rather to learn from it. This implies that any ongoing restrictions, and any new burdens placed on small businesses, need to be based on robust and verifiable science, not just on rules-of-thumb. Going forward, policy-makers will have to do a better job of taking into account the impact of their legislative edicts on poverty and economic well-being.

Job Costs of the Lockdowns

Between the start of the crisis and April, Canada’s unemployment rate nearly tripled to 13.7%, with Quebec’s almost quadrupling to 17%. If we include people who have given up looking for work, job losses roughly double. In Quebec, 820,000 jobs were lost in March and April, about one job in five.(4) Including reduced work hours, an estimated 5.5 million Canadian workers were affected by the pandemic shutdowns.(5)

With every province locking down, the crisis was nationwide, and concentrated in blue-collar sectors where working from home is not an option, including construction, manufacturing, wholesale and retail trade, and accommodation and food services, four sectors that together made up 59% of job losses in April compared to a year before.(6)

Then in May, Quebec started to reopen, while the rest of Canada largely adopted a wait-and-see attitude. Quebec eased restrictions on blue-collar industries—construction in mid-April, then manufacturing and retail outside Montreal.(7) Right on cue, jobs soared in all three sectors. In that single month, Quebec’s overall unemployment rate plunged by 3.3 percentage points, while it rose in the rest of Canada, as limited job gains were swamped by discouraged workers returning to the labour market to seek employment.(8)

Fiscal Costs of the Lockdowns

Job losses provide one indication of the enormous cost of lockdowns; public finances provide another. Before the crisis, Quebec enjoyed a budget surplus and was making ongoing contributions to the Generations Fund.(9) Meanwhile, Ottawa was piling up debt, reporting an $11-billion deficit for the first nine months of the 2019-2020 fiscal year.(10)

The lockdown changed everything. Within weeks, Quebec had given out $19 billion in assistance or tax deferments.(11) Finance Minister Girard warned that it may take five years to balance the books again, estimating that the eight-week shutdown alone affected 40% of Quebec’s economic output, and will result in a $14.9-billion deficit for the fiscal year. He indicated that every month the shutdown is extended costs Quebec 3% of annual GDP and $5 billion in lost government revenue.(12)

As for the federal government, in April, it had already announced $257 billion in tax programs and fiscal measures in response to the crisis.(13) On May 26, the Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) estimated a 12% fall in GDP for 2020—the largest recorded in modern times—and a concomitant $260-billion federal deficit for fiscal 2021, dwarfing any federal deficit in history.(14) That works out to over $18,000 of new debt per Canadian household.(15)

Paying for the Lockdowns

The PBO is already warning that federal tax hikes are inevitable unless Ottawa makes a “sharp turn” to rein in spending. Some already worry of “brutal” tax hikes for the middle class.(16)

Of particular concern are a death tax and capital gains tax hikes, both of which could cripple investment, thereby kneecapping the recovery. While business tax hikes aren’t yet on the table, a government faced with the choice of raising taxes on job creators or on the median voter will often choose short-sightedly.

Even here in Quebec, dark clouds are coming from Economy Minister Fitzgibbon, who ominously pronounced that “we will have to forget what we learned in our schoolbooks,” as if basic economic principles don’t apply in a crisis.(17) Economists elsewhere have even floated discriminatory taxes on unpopular industries.(18)

The longer this government-induced depression continues, the more harm will be inflicted, and the louder will be the calls to raise taxes on the very people we need to invest and to hire our way out of this crisis.

References

- Statistics Canada, Table 14-10-0287-03: Labour force characteristics by province, monthly, seasonally adjusted, 2020; Shelly Hagan, “Canada unexpectedly adds 290,000 jobs on gradual reopening,” Financial Post, June 5, 2020; Chris Fox, “Ontario reports lowest single-day increase in new COVID-19 cases in more than three weeks,” CP24, April 29, 2020.

- Trading Economics, “Unemployment Rate,” 2020.

- Montreal Economic Institute, “What Would an ‘Intelligent Lockdown’ Look Like in Canada?” June 25, 2020.

- Statistics Canada, op. cit., endnote 1.

- Sherry Cooper, “Good News in May Jobs Report—10.6% Recovery in COVID Losses,” Dominion Lending Centres, June 5, 2020.

- Benjamin Shingler, “Quebec unemployment rate soars to 17%, highest ever recorded,” CTV News, May 8, 2020.

- Government of Quebec, Gradual resumption of activities under the COVID-19-related pause, June 17, 2020.

- Sherry Cooper, op. cit., endnote 5; Statistics Canada, op. cit., endnote 1.

- Amy Luft, “Highlights from Quebec’s 2020-2021 budget,” CTV News, March 10, 2020.

- The Canadian Press, “Federal government runs $11-billion deficit for April-to-December period,” CTV News, February 28, 2020.

- Hugo Pilon-Larose, “Après la pandémie, la crise des finances publiques,” La Presse, April 13, 2020.

- Government of Quebec, Québec’s Economic and Financial Situation 2020-2021, June 2020, p. A11; Frédéric Tomesco, “No tax increases, Quebec finance minister pledges,” The Province, May 29, 2020.

- Hugo Pilon-Larose, op. cit., endnote 11.

- Jesse Snyder, “Tax hikes ‘unavoidable’ to offset raft of COVID-19 spending, federal budget watchdog says,” National Post, May 26, 2020.

- Statistics Canada, The Daily, Table 1: Number of households, median income and median income rank, Canada, provinces and territories, September 27, 2017.

- Joe Oliver, “Brace yourself for brutal tax hikes—and not just for the rich,” Financial Post, June 11, 2020.

- Hugo Pilon-Larose, op. cit., endnote 11.

- Jesse Snyder, op. cit., endnote 14.