Emergency Rooms: Fewer Patients, Longer Waits

Earlier this year, the media reported that the situation in Quebec emergency rooms had improved in 2018-2019. Yet when we take a closer look at the Department of Health and Social Services data, we see that the opposite has happened, despite a reduction in the number of patient visits.

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| Urgences – Moins de patients, plus d’attente (La Presse+, August 21, 2019) | Interview (in French) with Patrick Déry (Dutrizac, QUB Radio, August 21, 2019)

Interview (in French) with Patrick Déry (Le retour d’Éric Duhaime, FM93, August 21, 2019) |

Interview (in French) with Patrick Déry (Le Québec matin, LCN-TV, August 21, 2019)

Report with Patrick Déry (CTV News Montreal at Noon, CFCF-TV, August 21, 2019) |

This Viewpoint was prepared by Patrick Déry, Senior Associate Analyst at the MEI. The MEI’s Health Policy Series aims to examine the extent to which freedom of choice and private initiative lead to improvements in the quality and efficiency of health care services for all patients.

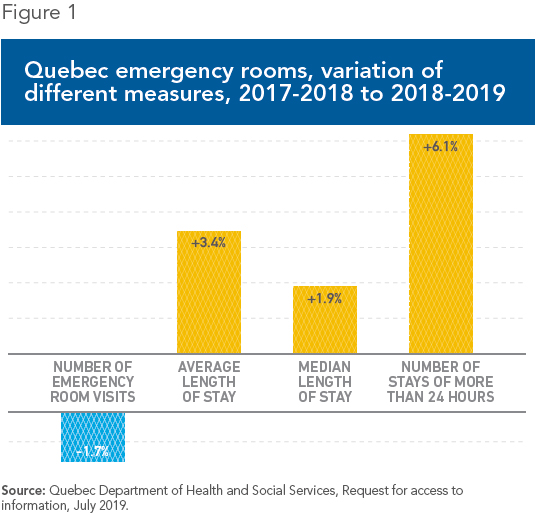

Earlier this year, the media reported that the situation in Quebec emergency rooms had improved in 2018-2019.(1) Yet when we take a closer look at the Department of Health and Social Services data, we see that the opposite has happened, despite a reduction in the number of patient visits.

The Fake Drop in 2017-2018

The media have long measured emergency room wait times using the average length of stay. In the 2017-2018 fiscal year, the average stay for patients on stretchers showed an impressive decline of nearly two hours. As for the average ambulatory patient stay, it had increased by eight minutes. Altogether, the average length of stay for patients having visited an emergency room was down almost half an hour. As for the number of stays exceeding 48 hours, it had fallen by half.(2)

By using the median length of stay, however, the reality was somewhat different. The reduction of nearly two hours for patients on stretchers became a gain of around twenty minutes (from 9.5 hours to 9.2 hours). The reduction of a half hour for all patients combined became a slight increase (from 4.4 hours to 4.5 hours). Why use the median rather than the average? Because it is less influenced by the extremes and more representative of patients’ experience.(3) For example, a substantial reduction in very long emergency room stays could have a large effect on the average, but would not change the reality of patients who spend five or ten hours there.

That seems to be what happened in 2017-2018. Moreover, the reduction in the number of stays of more than 48 hours was due at least in part to moving patients out of the emergency room, not to more timely care.(4) Nonetheless, one could hope that a downward trend had begun.

Increases across the Board in 2018-2019

In 2018-2019, the picture is clearer: All measures are worsening. The median length of stay for patients on stretchers increased by 14 minutes (to 9.4 hours), erasing a good part of last year’s reduction. It increased by two minutes (to 3.3 hours) for ambulatory patients, and by five minutes (to 4.6 hours) for all patients combined. Indeed, despite some fluctuations, the median length of stay for patients on stretchers is the same as it was fifteen years ago, while for ambulatory patients, it has increased by 50%.(5) In many Quebec hospitals, especially in Montreal and in the neighbouring communities to the north and south, stays of ten or twelve hours for an infection or minor injury are not uncommon.(6)

The situation is not better for the number of very long stays, which has started increasing again after last year’s spectacular (but artificial) reduction. Some 221,151

patients waited more than 24 hours before being hospitalized or returning home last year, a 6.1% increase in one year, while 36,199 patients remained on a stretcher for more than 48 hours, a 21% increase.(7)

Most worrisome, both from a public policy and from a patient’s point of view, is that these increases occurred while, for the first time in many years, the total number of emergency room visits decreased, by 1.7% (see Figure 1).(8) It’s not that the clientele deteriorated, either: The number of patients aged 75 and over increased (1.7%), but less than in previous years (4.9% and 5.9%). And the number of more urgent cases continued to fall (Priority 1), or increased less than before (Priorities 2 and 3).(9)

The public administration of hospitals seems to have reached its limits, and our health care system’s chronic problems seem to have worsened. To the delays that earn Quebec last place in the Western world(10) have been added staff shortages leading to overwork, and to new shortages, all against a background of mandatory overtime.(11)

Embracing Entrepreneurship

Surprisingly, proven remedies are slow to be applied. Indeed, the health care systems of Quebec and of the rest of Canada are exceptions among industrialized countries. Everywhere else, the existence of universal coverage is accompanied by an embrace of entrepreneurship. Germany, Australia, Spain, France, and Italy are all countries whose health care systems are based on principles of universality, and where more than a third of hospitals are private and for-profit.(12)

Even in Quebec, we have seen proof that the search for profit can exist in a universal health care system and be of significant benefit to patients. One need only think of the private funded CHSLDs (long-term care facilities), which offer better care at a lower cost than equivalent government-managed facilities,(13) or of pilot projects for surgeries that are underway in the Montreal region, which have shrunk waiting lists thanks to much higher productivity than in public hospitals.(14)

Quebec is ripe for the application of the same recipe to hospitals and emergency rooms. A large majority of Quebecers (70%) are actually in favour of more entrepreneurs providing care, all while maintaining universal coverage.(15) The way things are going, this would be a great boon for the province’s patients.

References

1. Ariane Lacoursière, “Palmarès des urgences: le Québec s’améliore, l’ouest de la Montérégie régresse,” La Presse, July 4, 2019.

2. Patrick Déry, “Quebec Hospitals Require Entrepreneurship,” Viewpoint, MEI, July 12, 2018; David Gentile, “Urgences au Québec : moins d’attente sur civière, autant d’attente sur chaise,” Radio-Canada.ca, April 21, 2018; Sara Champagne, “Une réduction du temps d’attente, mais à quel prix,” La Presse+, July 19, 2018.

3. Median length of stay is used in the rest of Canada and elsewhere. Canadian Institute for Health Information, “NACRS Emergency Department Visits and Length of Stay by Province/Territory, 2017–2018,” November 29, 2018; Patrick Déry and Jasmin Guénette, “Saint Göran: A Competitive Hospital in a Universal System,” Economic Note, MEI, October 17, 2017.

4. Ariane Lacoursière, “Attente aux urgences : du camouflage de patients, selon des intervenants,” La Presse, April 20, 2017; Agence QMI, “Temps d’attente aux urgences en baisse : des statistiques trompeuses?” Le Journal de Montréal, April 25, 2018.

5. For the data from 2014 to 2019: Quebec Department of Health and Social Services, Request for access to information, July 2019. For earlier data: Health and Welfare Commissioner, Les urgences au Québec : évolution de 2003-2004 à 2012-2013, Government of Quebec, September 17, 2014, pp. 14-15.

6. Quebec Department of Health and Social Services, Request for access to information, July 2019.

7. Idem.

8. It went from 3,776,013 to 3,711,052. Idem.

9. Idem.

10. Tommy Chouinard, “Les pires urgences du monde occidental,” La Presse, June 2, 2016; Health and Welfare Commissioner, Perceptions et expériences de la population : le Québec comparé − Résultats de l’enquête internationale sur les politiques de santé du Commonwealth Fund de 2016, Government of Quebec, February 16, 2017, p. 43.

11. Stéphane Parent, “Le Québec compte plus de 75 000 infirmières dont 70 489 occupent un emploi en soins infirmiers et ce n’est pas assez!” Radio-Canada International, October 24, 2018; Héloïse Archambault, “Temps supplémentaire obligatoire : des infirmières sont prisonnières à l’hôpital,” Le Journal de Montréal, April 8, 2019.

12. Yanick Labrie, For a Universal and Efficient Health Care System: Six Reform Proposals, Research Paper, MEI, March 13, 2014, p. 19.

13. Patrick Déry, “Relying on Entrepreneurs to House and Care for Our Seniors,” Viewpoint, MEI, April 26, 2018.

14. Caroline Touzin, “Projet-pilote en chirurgie : la productivité bondit au privé,” La Presse, April 23, 2019; Francis Vailles, “Pourquoi se priver du privé,” La Presse, May 3, 2019.

15. Leger, “Les Québécois et la santé – Sondage auprès des Québécois,” poll conducted on behalf of the MEI, August 30, 2018.