Ottawa Should Simplify the Income Tax Act

Taxpayers always meet the months of March and April with some apprehension, as they will have to devote precious hours of their time to completing their income tax returns, or pay someone else to do it for them. Is it possible to make life easier for taxpayers by simplifying the tax system?

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| Filing a tax return in less than a million words (National Post, April 10, 2019) | Interview (in French) with Kevin Brookes (Mario Dumont, LCN-TV, April 10, 2019) |

This Economic Note was prepared by Kevin Brookes, Associate Researcher at the MEI, in collaboration with Mathieu Bédard, Economist at the MEI. The MEI’s Taxation Series aims to shine a light on the fiscal policies of governments and to study their effect on economic growth and the standard of living of citizens.

Taxpayers always meet the months of March and April with some apprehension, as they will have to devote precious hours of their time to completing their income tax returns, or pay someone else to do it for them. Is it possible to make life easier for taxpayers by simplifying the tax system?

Simplicity is one of the recognized principles for judging the quality of a tax system. Such a system must among other things be comprehensible by all and provide certainty regarding the amounts to be collected.(1) Yet over the years, the government of Canada has gradually moved away from these guidelines. Its tax system has become more and more complicated and expensive to administer, and compliance has also become more difficult.(2)

Despite its considerable expansion since its creation, the Income Tax Act has not been subjected to a detailed examination for a little over half a century.(3) Numerous specialists, professional associations, and parliamentarians believe that the time has come to carry out this exercise.(4) The experience of the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand, three Commonwealth countries, can serve as inspiration for Canada and provide an overview of possible reforms that could be undertaken here.

The Problem of Tax Complexity

Tax complexity can be defined as the set of factors that make the tax system harder to understand for all the people it affects. It refers both to its design (number and kinds of taxes, of rates, and of tax credits) and to how easy compliance is (number of steps required to complete a tax return, inconsistencies in the system, frequency of changes, and simplicity of the language used).(5)

This tax complexity poses four major problems. First, it is unfair: People who earn the same income end up paying different amounts of income tax due to fiscal rules. This lack of fairness is the result of the intense activity of organized groups that lobby to obtain benefits, or of electoral calculations.(6) Second, it represents a substantial cost for taxpayers in time and money devoted to completing their tax returns, but also for the government since collecting taxes becomes more expensive. Third, it creates uncertainty for taxpayers, which makes it more difficult for them to plan their personal finances. Finally, it can encourage tax evasion.(7)

In contrast, a simple tax system means taxpayers are “more likely to understand how they are being taxed, to be able to comply with their obligations and to be in a better position to make economic decisions.”(8)

The Income Tax Act: Too Complex and Too Burdensome

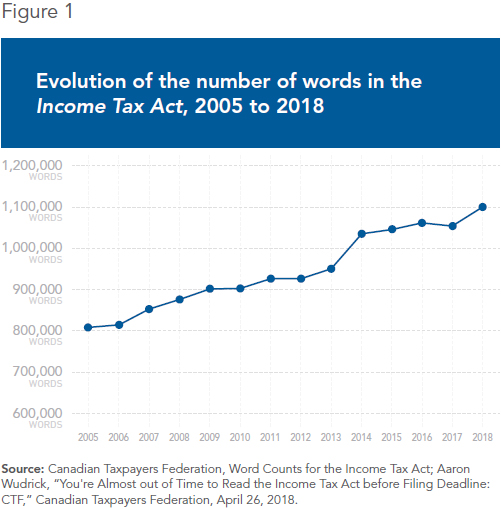

The Canadian tax system is very complex, and has become more so in recent years. Whereas the Income Tax Act was 4,000 words long when it was enacted in 1917, today it comprises over 1.1 million words, or the equivalent of the seven volumes of the Harry Potter series combined.(9) The law is 275 times longer today than when it was created.(10) Just since 2005, it has gotten 36% longer (see Figure 1). In addition to being massive, the Income Tax Act is not easy to understand, even for civil servants: Nearly one third of responses given to taxpayers by Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) call centre agents are wrong.(11)

Another aspect of the complexity of the Canadian system is the high number of personal tax credits, which represent exceptions that must be taken into account when completing a tax return. The number of these credits increased by 26% between 1991 and 2015, and their total value by 74%.(12) During this period, four times as many new tax credits were created as were eliminated.(13)

In addition to being largely unfamiliar to the general public, these deductions and exceptions have not always accomplished their goals efficiently. For example, the tax credit for children’s physical education and the tax credit for children’s artistic activities did not have an influence on the choices of parents to sign their children up for such activities or not.(14) Indeed, according to a poll, 71% of chartered professional accountants think that the system of tax deductions is too complicated.(15)

The federal General Income Tax and Benefit Guide should also be simplified. This guide, which was 74 pages long in 2017, still had 52 pages in 2018.(16) Despite the efforts made to reduce the number of pages and of instructions, and to simplify the language, the very existence of such a voluminous guide is itself evidence of the complexity of the task of completing one’s tax return.

A Doubly Expensive System

The length of the Income Tax Act, its inaccessible language, and its numerous exceptions increase the cost of complying for taxpayers. On average, this cost amounted to $501 per Canadian household in 2012.(17) This complexity hits low-income taxpayers even harder, as they devote a larger proportion of their income to complying with the law.(18)

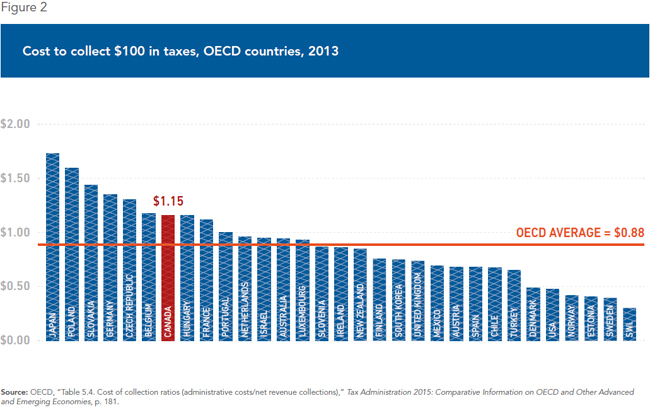

Tax complexity is also expensive for taxpayers because of the additional resources the government has to devote to managing its tax system. Figure 2 shows that Canada’s tax system is costlier to administer than the OECD country average. For every $100 of tax revenue collected, the Canadian government must spend $1.15, or around 50% more than in the United Kingdom, for instance. Moreover, Canada requires a large number of civil servants to apply its tax laws: There are around 40,000 CRA employees, fully half the number of people employed by the American IRS, despite the latter having to process the files of five times as many taxpayers.(19)

Finally, the number of legal disputes between taxpayers and the CRA is growing, as are the amounts concerned. Just having access to a civil servant is difficult, since the CRA answers only a little over one in three calls. Total outstanding federal tax dollars in dispute were multiplied by a factor of three between 2005-2006 and 2015-2016, and the number of files outstanding increased to a similar degree, from 63,384 to 171,744.(20)

Lessons from Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom

While Canada has made no major revisions of its Income Tax Act since the 1960s, New Zealand, Australia, and the United Kingdom have done so several times in the past 25 years. All of these countries have implemented measures to reduce the size and the complexity of their tax codes. Notably, ad hoc committees and even permanent agencies were created in order to simplify the tax system.

In the United Kingdom, between 1996 and 2010, the “Tax Law Rewrite” project rewrote 6,000 pages of laws regarding personal and corporate income taxes, in order to simplify them. The outcome was considered positive both by the government and by accountants.(21)

The “Office of Tax Simplification” was then created in 2010 to provide independent advice to the Finance Minister. In order to evaluate the efforts required by the government and to set objectives by sector, it established a tax complexity index. This index takes into account among other things the number of changes to the law over the years, the number of pages that make up the text of the law, the readability of the legislation, the cost borne by taxpayers, etc. The Office of Tax Simplification also carried out an examination of a sample of tax credits and proposed that certain of them be abolished or simplified.(22)

In New Zealand, the “Organisational Review of Inland Revenue” was created in 1994. Experts were mandated to rewrite, but also to reorganize, tax laws as well as the documents used to communicate with citizens. This rewriting process, carried out in a collaborative manner, made the law easier to read for taxpayers and for those who complete their tax returns.(23) Indeed, the New Zealand government has received awards for the clarity of the English used to communicate with taxpayers, whether through the use of websites, guides, or simplified tools (like a mobile application for taxpayers and business leaders).(24)

In 1993, the Australian government established a team to reorganize the tax code and rewrite it in modern English, in the context of a “Tax Law Improvement Project.” Eventually, 30% of the content of the law was eliminated.(25)

In all of these countries, the agencies charged with examining the tax code drew on the expertise of academics and of professionals.(26) Civil servants were thus not alone in examining the tax system, since such an exercise requires much more freedom of speech than what government employees are generally allowed.(27) This also avoids putting them in the position of being both the judges and the judged.

Conclusion

A detailed examination of Canada’s tax system is needed, and its goal should be simplification. However, it would be against the interest of taxpayers—and frankly absurd—for the elimination of tax credits to lead to a net increase in effective income tax rates. The trade-off to the elimination of tax credits of all sorts should thus be an equivalent lowering of income tax rates. This would lower the cost of tax collection both for the government and for taxpayers without affecting government tax revenues, all while making the system easier to understand.

Besides the elimination of tax credits, foreign experience shows us other avenues, like simplifying the language of the law, reducing its size, using a tax complexity index, and improving communication with taxpayers. A significant effort to simplify the tax system would, through the increased transparency of the system, end up refocusing the debate on more crucial questions in our democracies, such as the share of incomes that the government collects from citizens compared to the benefits they receive.

References

1. OECD, Chapter 2: Fundamental principles of taxation, Addressing the Tax Challenges of the Digital Economy, 2014, p. 30.

2. François Vaillancourt and Charles Lammam, “Compliance Costs and Complexity in Canada’s Personal Income Tax,” in William Watson and Jason Clemens (eds.), The History and Development of Canada’s Personal Income Tax, Fraser Institute, 2017, p. 33.

3. Alan Macnaughton and Kevin Milligan, “Policy Forum: Editors’ Introduction—Should Canada Have a Tax Commission?” Canadian Tax Journal, Vol. 66, No. 2, 2018, pp. 349-350.

4. Including the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance, the Standing Senate Committee on National Finance, the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada, the Advisory Council on Economic Growth, the Business Council of Canada, and the Canadian Chamber of Commerce.

5. David Ulph, “Chapter 4: Measuring Tax Complexity,” in Chris Evans, Richard Krever, and Peter Mellor (eds.), Tax Simplification, Wolters Kluwer, 2015, pp. 43-49.

6. Simon James, Arian Sawyer, and Ian Wallschutzky, “Tax simplification: A review of initiatives in Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom,” eJournal of Tax Research, 2015, Vol. 13, No. 1.

7. David Ulph, op. cit., endnote 5, pp. 48‑49.

8. Tamer Budak, Simon James, and Adrian Sawyer, “The Complexity of Tax Simplification: Experiences from Around the World,” in Simon James, Adrian Sawyer, and Tamer Budak (eds.), The Complexity of Tax Simplification: Experiences from Around the World, Palgrave MacMillan, 2016, p. 3.

9. Government of Canada, Justice Laws Website, Consolidated Acts, Income Tax Act (R.S.C., 1985, c. 1 (5th Supp.)), Act current to 2019-02-14; WordCounter, “How Many Words Are There in the Harry Potter Book Series?” blog, November 23, 2015.

10. François Vaillancourt and Charles Lammam, op. cit., endnote 2, p. 34.

11. Office of the Auditor General of Canada, Report 2—Call Centres—Canada Revenue Agency, Accuracy, Fall 2017. Period from March 2016 to March 2017.

12. Department of Finance Canada, Report on Federal Tax Expenditures – Concepts, Estimates and Evaluations, 2017, p. 285.

13. Ibid., pp. 300‑301.

14. Ibid., p. 317.

15. Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada, Canada’s Tax System: What’s so Wrong and Why it Matters, 2018.

16. Canada Revenue Agency, General Income Tax and Benefit Guide, 2017; Canada Revenue Agency, Federal Income Tax and Benefit Guide, 2018.

17. Sean Speer et al., “The Cost to Canadians of Complying with Personal Income Taxes,” Fraser Institute, April 2014, p. 31.

18. Government of Canada, Budget 2018, February 27, 2018, p. 275; Sean Speer et al., ibid., p. 27.

19. Canada Revenue Agency, 2017-18 Departmental Results Report, November 20, 2018, p. 60; Internal Revenue Service, Internal Revenue Service Data Book, 2017, p. 66; Canada Revenue Agency, Individual Tax Statistics by Tax Bracket 2018 Edition (2016 tax year), Table 1: Individual Taxfilers by Province or Territory and Tax Bracket; Erica York, “Summary of the Latest Federal Income Tax Data, 2017 Update,” Fiscal Fact, No. 570, Tax Foundation, January 2018, p. 2.

20. Office of the Auditor General of Canada, Report 2—Income Tax Objections—Canada Revenue Agency, Fall 2016; Office of the Auditor General of Canada, op. cit., endnote 11.

21. Tamer Budak and Simon James, “The Level of Tax Complexity: A Comparative Analysis between the U.K. and Turkey Based on the OTS Index,” International Tax Journal, January-February 2018, p. 30; Simon James, “The Complexity of Tax Simplification: The UK Experience,” Simon James, Adrian Sawyer, and Tamer Budak (eds.), The Complexity of Tax Simplification, 2016, pp. 235‑236.

22. Gareth Jones et al., “Developing a tax complexity index for the UK,” Office of Tax Simplification, 2014, pp. 2-3; Simon James, “The Complexity of Tax Simplification: The UK Experience,” ibid., pp. 240-242.

23. Adrian Sawyer, “Complexity of Tax Simplification: A New Zealand Perspective,” Simon James, Adrian Sawyer, and Tamer Budak (eds.), The Complexity of Tax Simplification: Experiences from Around the World, 2016, p. 119.

24. Simon James, “The Complexity of Tax Simplification: The UK Experience,” op. cit., endnote 21, pp. 120-122.

25. The group rewrote certain laws, but its mandate ended a few years later, leaving its work uncompleted. Binh Tran-Nam, “Tax Reform and Tax Simplification: Conceptual and Measurement Issues and Australian Experiences,” Simon James, Adrian Sawyer, and Tamer Budak (eds.), The Complexity of Tax Simplification: Experiences from Around the world, 2016, pp. 22-28.

26. Chris Evans, “Reviewing the Reviews: A Comparison of Recent Tax Reviews in Australia, the United Kingdom and New Zealand or ‘a Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum’,” Journal of Australian Taxation, Vol. 14, No. 2, 2012, pp. 149‑157.

27. Jennifer Robson, “Policy Forum: Building a Tax Review Body That Is Fit for Purpose—Reconciling the Tradeoffs Between Independence and Impact,” Canadian Tax Journal, Vol. 66, No. 2, 2018, pp. 379‑380.