How Innovation Benefits Forests

The accumulation of knowledge and technological change have led to a significant shift in forestry practices. As a result, forestry is now a sustainable activity supporting the economy in many parts of Canada. Despite this reality, various popular myths lead people to believe that wood harvests need to be reduced to ensure forest survival. On the contrary, the potential of Canadian forests is in fact underutilized, presenting opportunities for hundreds of forest-dependent towns and regions across the country.

Media release: Our forests are in good health: They are not overharvested

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| Combattre des mythes sur la récolte forestière (Le Quotidien, September 18, 2018) |

This Economic Note was prepared by Alexandre Moreau, Public Policy Analyst at the MEI. The MEI’s Environment Series aims to explore the economic aspects of policies designed to protect the natural world in order to encourage the most cost-effective responses to our environmental challenges.

The accumulation of knowledge and technological change have led to a significant shift in forestry practices. As a result, forestry is now a sustainable activity supporting the economy in many parts of Canada. Despite this reality, various popular myths lead people to believe that wood harvests need to be reduced to ensure forest survival.(1) On the contrary, the potential of Canadian forests is in fact underutilized, presenting opportunities for hundreds of forest-dependent towns and regions across the country.

No less than one-third of the Canadian population lives in or near forested areas.(2) In Quebec alone, the forestry sector accounts for 2% of GDP ($6.5 billion) and 1.6% of jobs, with nearly 59,000 workers.(3) In some parts of Quebec’s north, home to most of the forest harvest, its economic footprint is much greater. For example, in the Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean region, forests provides 10% of jobs, and in the Northern Quebec region, more than 40%.(4) Forestry is a major part of the economy for some 200 Quebec municipalities.(5)

Canada’s Forests Are Healthy

Despite ongoing activities, Canada’s forest cover has remained relatively stable since 1990. This trend should continue over the next 10 to 20 years.(6) Contrary to what some believe, forest harvesting is not synonymous with deforestation.

According to the definition used by the Government of Canada, the concept of deforestation refers to permanent change in land use due to human activity.(7) Others use a broader definition to include areas heavily disrupted by human activity and natural phenomena, such that regeneration becomes unlikely in the long term.(8)

Wood harvesting in managed forests is not regarded as deforestation since trees grow back naturally with the help of silviculture and can be harvested again in the future. In this case, it is permanent forest roads that can affect the use of forests and cause a reduction in forest cover. Moreover, the area deforested annually in this way has fallen by over half since 1990 and accounts for only a tiny portion of Canada’s forest land.(9)

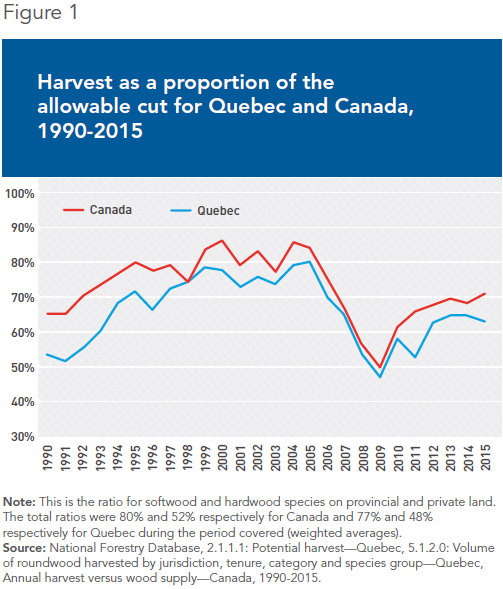

Historically, the harvest level has always been far less than what forests could produce. Indeed, wood harvest expressed as a percentage of the allowable cut, meaning the maximum volume that can be harvested without reducing the forest’s capacity to renew itself, is relatively low in Quebec and all across Canada. On average, during the period from 1990 to 2015, this amounted to only 66% and 73%, respectively, of the allowable cut (see Figure 1).(10) In other words, the quantity of wood harvested each year is less than the interest earned on the forest capital.

Even in absolute terms, the volumes of wood harvested annually are now substantially lower than the levels observed in the early 1990s, and lower by an even greater margin than the peaks reached in the early 2000s. Indeed, the softwood harvest, accounting for more than three-quarters of the total harvest, fell by 9% in Canada and by nearly 20% in Quebec.(11) These variations are due largely to changes in demand for forest products,(12) but also to innovation in the sector.

The Profit Motive Protects Our Forests

In the quest for profit, companies make substantial investments to reduce waste and thereby get the most out of each tree harvested, regardless of defects. In the sawmilling sub-sector, the use of new technologies enables increased production while using fewer and fewer trees.(13)

Between 1990 and 2017, the volume of softwood roundwood needed to produce 1,000 board feet fell by nearly a quarter.(14) Sawmills would have consumed more than 30 million m3 of roundwood in 2017 if they had recorded the same yield as in 1990, or some 7 million m3 more. This level of consumption would have been higher than what Quebec’s forests are currently able to sustain and might well have endangered them in the long term.(15)

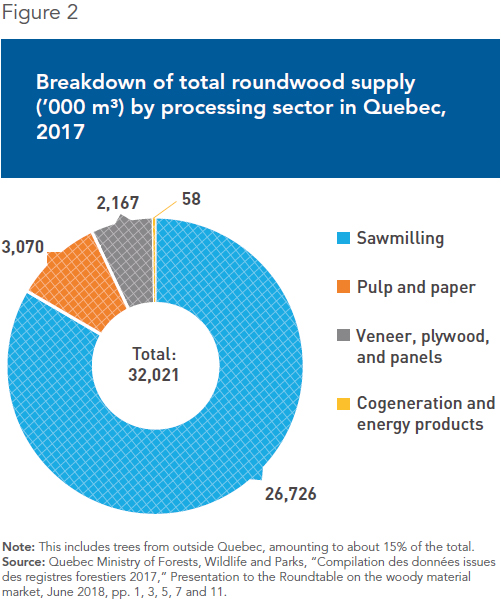

Increased yield from sawmills is critical since they consume more than 80% of the wood harvested, with nearly all of this coming from species of fir, spruce, jack pine and larch (FSPL).(16) Other trees are used primarily to supply pulp and paper mills or plants producing composite materials (see Figure 2).

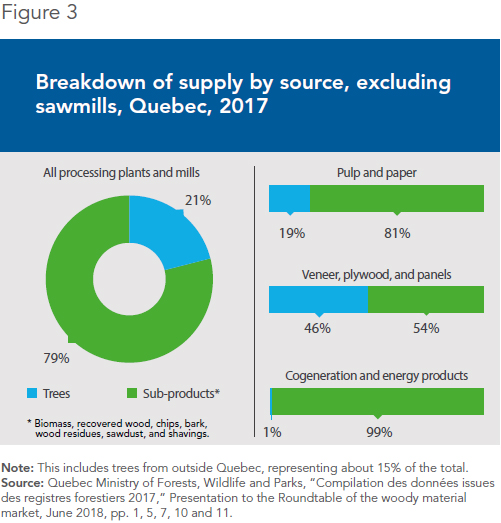

In the overall forest industry, only sawmills are supplied exclusively by trees. Sawmill residues are recovered by plants in other sectors; chips, bark, sawdust, shavings, and other recycled products account for nearly 80% of these plants’ supply (see Figure 3).

In the specific case of pulp and paper mills, the figure is 81%. This is an impressive gain, given that the comparable figure was about 60% in the early 1990s, and only 20% in the 1970s.(17) As in the case of sawmills, these efficiency gains allowed for greater production while cutting down fewer trees.

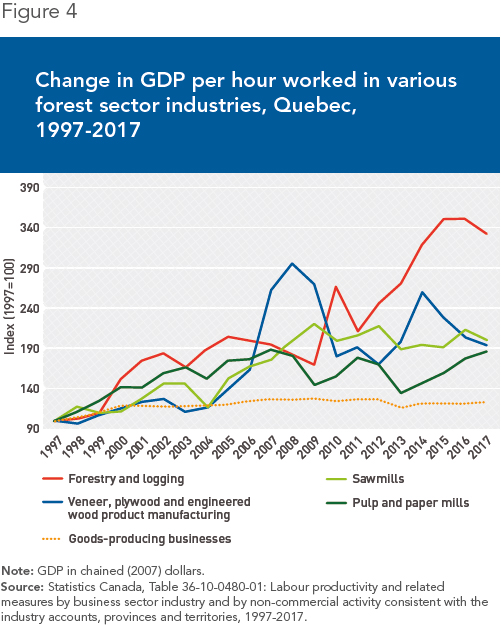

The value added to sawmilling sub-products has boosted productivity in the forest sector, with the wealth derived from each tree continuing to rise.(18) The same applies when measuring it according to the number of hours worked. In Quebec, GDP per hour worked has essentially doubled over the last 20 years in the various forest-related sectors. The comparable increase was only about 23% for goods-producing industries as a whole (see Figure 4). On a Canada-wide basis, productivity growth in forestry-related sectors has also been significantly higher than in goods-producing industries generally.(19)

The Impact of Forest Management Policies

Forest management policies affect the predictability and stability of supply and, ultimately, the ability of plants to invest in meeting consumers’ needs. Canada-wide, the vast majority of the harvest and of the allowable cut is in public forests, which account for more than 90% of all forests.(20) Management policies therefore have a major impact on the economic activity of the forest sector.

Indeed, the volumes of wood allocated for harvesting have fallen by nearly one-quarter since the early 2000s in Quebec, due in particular to the establishment of protected areas.(21) In the long term, this may lead to artificial scarcity and may push up procurement costs for processing plants. Moreover, lack of access to public forests may limit the ability of plants to meet growing global demand for certain products.(22)

To remedy this situation, Quebec’s Bureau du forestier en chef has urged the Minster of Forests, Wildlife and Parks to consider a strategy review, raising the allowable cut by 25% between now and 2038 and by 50% by 2063. Among other things, this would involve intensifying forest management activities with the use of silviculture to boost the regenerative capacity and, in the final analysis, the yield of public forests. This would ensure a predictable and stable supply level, conducive to investment and production planning for processing plants.(23) Once again, the application of new knowledge in forest management would thus help increase the volumes of wood available for harvesting, all while preserving the resource.

Conclusion

Thanks to innovation, forestry activity does not threaten the sustainability of our forests. Improved performance at mills and plants and increased upgrading of sub-products from processing have helped boost economic activity despite the government’s reduction of the volumes of wood available for harvesting. This latter trend is likely to continue, given the desire to expand protected areas and preserve species at risk.

No one contests the need to put in place conservation measures. Thankfully, today’s technology and methods allow the forest to be harvested in a way that respects the environment, meeting both social expectations with regard to respecting biodiversity and the economic needs of the workers and communities that depend on the forest. Recent history teaches us that the profit motive will be a great help in this regard.

References

1. Nicolas Mainville, “Vous ne croirez pas ces six statistiques sur la forêt québécoise,” Greenpeace, March 17, 2016.

2. Natural Resources Canada, The State of Canada’s Forests – Annual Report 2017, 2017, p. 47.

3. These numbers refer to jobs and direct GDP, expressed in chained (2007) dollars, for the year 2017. They cover the primary sector (NAICS 113 and 1153) and the direct manufacturing sector (NAICS 321 and 322). Statistics Canada, Table 14-10-0201-01: Employment by industry, monthly, unadjusted for seasonality, 2017; Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0402-01: Gross Domestic Product (GDP) at basic prices, by industry, provinces and territories, 2017.

4. Job data by region are from 2013, but nothing suggests the proportions have changed significantly. Given the increased forest harvest since then, these proportions are conservative. Alexandre Moreau, Quebec’s Forest Regimes: Lessons for a Return to Prosperity, Research Paper, MEI, October 2016, p. 35.

5. Bureau du forestier en chef, État de la forêt publique du Québec et de son aménagement durable : Bilan 2008-2013, 2015, p. 18.

6. Forest cover has fallen by only 0.34% and stood at 347.1 million hectares in 2015. Natural Resources Canada, op. cit., endnote 2, p. 27.

7. This Natural Resources Canada definition is based on the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Andrew Dyk et al., Canada’s National Deforestation Monitoring System: System Description, Natural Resources Canada, 2015, p. 2.

8. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Deforestation.

9. Deforestation caused by forest roads amounted to only 1,400 hectares in 2015. Natural Resources Canada, op. cit., endnote 2, p. 28.

10. The harvest level for softwood species was high in Quebec at the turn of the 2000s, but did not jeopardize the sustainability of the resource. Alexandre Moreau, op. cit., endnote 4, pp. 17-25.

11. These are the variations between the 1990-1994 and 2011-2015 periods, to offset annual volatility. National Forestry Database, 2.1.1.1: Potential harvest—Quebec, 5.1.2.0: Volume of roundwood harvested by jurisdiction, tenure, category and species group—Quebec, Annual harvest versus wood supply—Canada, 1990-2015.

12. Alexandre Moreau, op. cit., endnote 4, pp. 33-34; Natural Resources Canada, op. cit., endnote 2, p. 31.

13. The yield is 25% to 35% higher in plants using new technologies. Quebec Ministry of Natural Resources, Wildlife and Parks, “La technologie du sciage et le rendement en bois d’œuvre résineux,” March 2004, pp. 3-4.

14. From 5.02 m3 to 3.84 m3. This covers FSPL (fir, spruce, jack pine, and larch) species only. Quebec Ministry of Forests, Wildlife and Parks, “Compilation des données issues des registres forestiers 2017,” presentation to the Roundtable on the woody material market, June 2018, p. 18. The yield for 1990 comes from the 2004 edition of the statistical portrait from the Quebec Ministry of Natural Resources, Wildlife and Parks, “Ressources et industries forestières : portrait statistique—Édition 2004,” June 2004, Table 00.05.03.

15. Consumption of FSPL species by sawmills was 23.2 million m3 in 2017; it would have been 30.3 million m3 with the 1990 sawmill yield. The net allowable cut in public forests was about 27 million m3 as of December 31, 2017, with 20.3 million m3 in public forests and about 7 million in private forests. Quebec Ministry of Forests, Wildlife and Parks, “Compilation des données issues des registres forestiers 2017,” Presentation to the Roundtable on the woody material market, June 2018, p. 4; Quebec Ministry of Forests, Wildlife and Parks, Répertoire des bénéficiaires de droits forestiers sur les terres du domaine de l’État—Version du 31 décembre 2017, 2017.

16. Quebec Ministry of Forests, Wildlife and Parks, “Compilation des données issues des registres forestiers 2017,” Presentation to the Roundtable on the woody material market, July 2017, pp. 4 and 11.

17. Ibid., pp. 1-2; Quebec Ministry of Natural Resources, Ressources et industries forestières : portrait statistique—Édition 1994, 1994, p. 102; Pierre Desrochers and Jasmin Guénette, Concilier profits et environnement : le recyclage des déchets industriels dans une économie de marché, Research Paper, MEI, April 22, 2005, pp. 24-25.

18. Bureau du forestier en chef, op. cit., endnote 5, p. 214.

19. Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0480-01: Labour productivity and related measures by business sector industry and by non-commercial activity consistent with the industry accounts, provinces and territories, 1997-2017.

20. Alexandre Moreau, op. cit., endnote 4, pp. 29-32.

21. Bureau du forestier en chef, Prévisibilité, stabilité et augmentation des possibilités, Opinion of the chief forester submitted to Luc Blanchette, Minister of Forests, Wildlife and Parks, December 2017, p. 12.

22. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, State of the World’s Forests 2009. Part 2: Adapting for the Future, 2009, pp. 64-69.

23. Bureau du forestier en chef, op. cit., endnote 21, pp. 14-23.