Air Transport: High Taxes and Fees Penalize Travellers

The Canadian air transport sector has experienced significant expansion in recent years. Nonetheless, a multitude of taxes and fees are restricting its potential for growth. Given that favourable conditions are dissipating, especially when it comes to low fuel prices, what can governments do to reduce the fees imposed on transporters, and ultimately on travellers?

Media release: Air transport: High taxes and fees penalize travellers

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| How high taxes and fees punish air travellers (The Globe and Mail, June 25, 2018)

Transport aérien: les frais pénalisent les voyageurs (Le Droit, June 20, 2018) |

Interview with Alexandre Moreau (Afternoons with Rob Breakenridge, 770 CHQR, June 21, 2018) | Interview (in French) with Alexandre Moreau (Mario Dumont, LCN-TV, June 21, 2018) |

This Economic Note was prepared by Alexandre Moreau, Public Policy Analyst at the MEI. The MEI’s Taxation Series aims to shine a light on the fiscal policies of governments and to study their effect on economic growth and the standard of living of citizens.

The Canadian air transport sector has experienced significant expansion in recent years. Nonetheless, a multitude of taxes and fees are restricting its potential for growth. Given that favourable conditions are dissipating, especially when it comes to low fuel prices,(1) what can governments do to reduce the fees imposed on transporters, and ultimately on travellers?

Air transport is an important aspect of any industrialized economy. In Canada, it generates no less than 230,000 direct jobs, and 130,000 indirect ones. This represents economic activity totalling a little over $35 billion, or 1.8% of the country’s economy.(2) In 2016, 140 million passengers were registered passing through Canadian airports.(3)

The particularities of a country like Canada obviously have an effect on the price its residents have to pay for a domestic or international flight. The country has the second largest land mass in the world, whereas its population is relatively small. This low population density means that there is a less developed market than that of other comparable countries, and that prices are higher.(4) This phenomenon is even more pronounced for flights connecting remote regions.(5)

Despite this geographical disadvantage, the number of passengers has nonetheless grown steadily in recent years. Between 2010 and 2016, the number of registered passengers in Canadian airports increased by nearly 29%, which represents annual growth of 4.3%. For the year 2017, the preliminary data indicate that the number of passengers has grown by 6.3%, which is significantly higher than the average in recent years.(6) Although domestic flights represent the majority of passengers (see Figure 1), the largest growth was observed for international flights.

Several economic factors can explain the increase in the number of passengers. First, the purchasing power of consumers has a notable effect on the decision to fly or not, and Canadians’ disposable income increased steadily between 2010 and 2016.(7) Also, average ticket prices for domestic and international flights decreased by 17% and 20% respectively, in real terms, over the same period.(8) This is largely due to the significant drop in the price of fuel,(9) a line item that represented around one third of airlines’ expenses when prices were higher.(10)

Finally, we must note the effect of the recent reform announced by the federal government, which aims to facilitate foreign investment in Canadian airline companies.(11) The arrival of new players, mainly low-cost airlines, has already led established companies to lower their prices and to offer new routes in an effort to maintain market share.(12)

What Governments Can Do

Obviously, there is nothing governments can do about long distances and a sparsely populated country. However, the federal government is ultimately responsible for the main Canadian airports as well as the passenger safety program. In conjunction with the provinces, it is also responsible for fuel taxes and goods and services taxes. Considering the negative effect of high charges and taxes on the sector’s economic activity, it goes without saying that governments could give a helping hand to this strategic sector.

This should start with lightening its burden of fees and taxes, especially given that Canada is no model in this regard. In 2017, a World Economic Forum report ranked Canada 68th out of 136 in terms of ticket taxes and airport fees, and 65th in terms of fuel prices.(13) According to another index, produced by the International Air Transport Association, Canada is ranked 31st out of 32 OECD countries in terms of the competitiveness of airport fees and taxes.(14)

The effect of all of these taxes and fees places Canadian airports at a disadvantage. According to a study produced by Raymond James Ltd., usage fees paid to Canadian airports by airline companies average $40.99 per passenger. That’s 50% more than the average of the ten most expensive American airports, and nine times higher than the average of the ten least expensive.(15) Clearly, Canada has a long way to go to ensure the competitiveness of its air transport sector.

Airport rents

Since 1992, the federal government no longer manages airports, which it now rents long-term to private, not-for-profit corporations. The organizations responsible for running the largest airports of the National Airports System (NAS) no longer receive any subsidies.(16) However, since the federal government remains the owner of almost all NAS airports,(17) it requires these organizations to pay rent that can represent up to 12% of their gross revenues. For the 2016-2017 fiscal year, Transport Canada thus collected $349 million from these airports.(18)

Air travellers security charge

In addition to rent, the federal government requires payment of a fee to cover security, which is the responsibility of the Canadian Air Transport and Safety Agency (CATSA). This agency was created in reaction to the September 11, 2001 attacks and is focused primarily on pre-boarding and luggage control.

It is perfectly normal for airlines to pay their share for security measures. However, the compulsory levy becomes problematic when it exceeds the expenses required for the proper functioning of the agency. For the 2016-2017 fiscal year, the federal government collected $768 million for passenger safety, which was $43 million more than it needed to cover spending. Although these surpluses are falling, over the past five years, Ottawa nonetheless collected nearly $404 million more than it spent on security.(19)

Federal and provincial taxes

Among the main taxes that apply to the air transport sector are federal and provincial excise taxes, which allow governments to collect substantial revenues. The federal excise tax on aviation fuel was introduced in the 1985 budget and set at 2¢ per litre. As of 1987, it was doubled to 4¢. This rate is still in effect except for international flights, which are exempt thanks to a multilateral agreement.(20) In addition to federal taxes, there are also provincial fuel taxes, which range from 3¢ to 11.14¢ per litre.(21) Then there are provincial and federal sales taxes totalling nearly $300 million a year.

The total revenue collected by all levels of government in the form of taxes, fees, and rent, either from consumers, from airlines, or from airports, exceeds $1.5 billion a year.(22) For at least some of these fees, we are far indeed from the “user pays” principle; they are merely a source of revenue for the government.

Less Tax, More Revenue

While it may be counterintuitive, reducing the taxes, fees, and rent it collects from airports would not necessarily entail a substantial loss of revenues for governments. This is because the demand for flights is very sensitive to price variations, especially for those travelling for the purpose of tourism.(23)

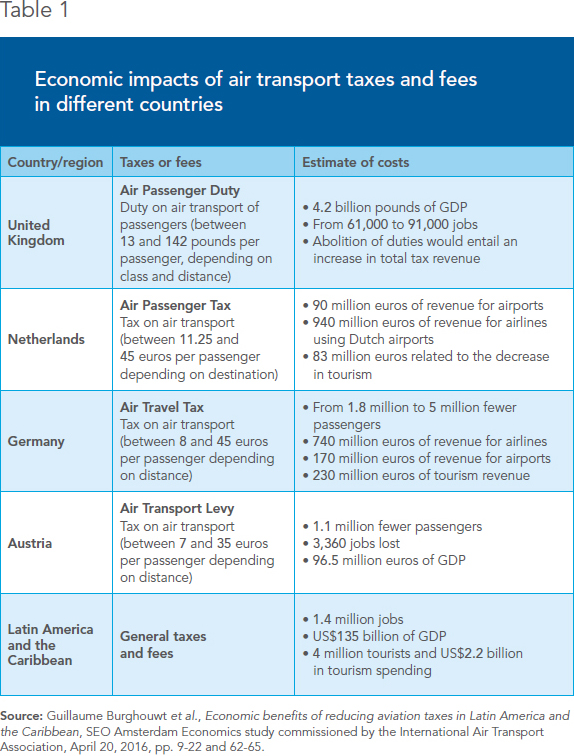

For short distances, higher prices inflated by taxes and fees that are applied only to air travel can lead users to choose another mode of transport that is less overtaxed. A 1% decrease in the price of tickets entails an increase in demand of 1.3% to 2% depending on the type of route.(24) Thus, if we reduced the burden of taxes and fees that weighs down the air transport sector, the resulting increase in economic activity and tax revenue would likely compensate for at least a portion of the lost government revenue. Indeed, one study concluded that in the United Kingdom, the abolition of fees on passenger transport would entail an increase in total tax revenue (see Table 1).

Moreover, when the value of the loonie approaches that of the American dollar, high taxes and fees can encourage Canadians to cross the border and take a flight from the United States.(25) The last time the two currencies were at parity, it was calculated that Canadian airports were losing five million passengers annually, mainly due to the price disparity from one country to the other. One third of this difference was due to higher fees and taxes in Canada.(26)

Finally, a high level of liberalization and competitive taxation in the air transport sector are strongly correlated with the level of trade around the world, and as a direct result of this, with downstream economic activity.(27) Several international examples illustrate the effect of taxes and fees on transportation and the growth of the air sector. As shown in Table 1, these fees do not need to be very high for a substantial impact to be felt.

Conclusion

Taken individually, none of these taxes and fees explains the high price of tickets in Canada, but their cumulative effect is clear. At the margin, they limit the growth of the air transport sector and the ensuing economic benefits. The tax burden that weighs on the air transport industry thus also weighs on the Canadian economy as a whole.

If they want to make the Canadian air transport industry more competitive and allow it to maintain its momentum, governments should reduce this burden, in parallel with the policy of opening up the sector to foreign investment. The industry is already at a disadvantage due to the particularities of this country. This is one more reason for governments to do everything they can not to hamper it. The government can’t bring Montreal and Vancouver closer, but it can certainly avoid making the trip more expensive than it needs to be.

References

1. Sabrina Bond, “Canadian Industrial Outlook: Air Transportation—Winter 2018,” Conference Board of Canada, April 10, 2018.

2. The data are for the year 2014. Oxford Economics, “The Importance of Air Transport to Canada,” Document prepared for the International Air Transport Association, December 2016, p. 1.

3. Statistics Canada, CANSIM Table 401-0044: Air passenger traffic at Canadian airports, 2010-2016.

4. Vivek Pai, “On the Factors That Affect Airline Flight Frequency and Aircraft Size,” Journal of Air Transport Management, Vol. 16, 2010, pp. 169-177.

5. Isabelle Dostaler, “Défis, enjeux, problématiques et pistes de solution du transport aérien régional,” Document d’amorce des discussions, Sommet sur le transport aérien régional au Québec, p. 2.

6. “Canadian airports report 6.3 per cent growth in 2017,” International Airport Review, February 9, 2018.

7. Statistics Canada, CANSIM Table 378-0153: Distributions of household economic accounts, income, consumption and savings, Canada, provinces and territories, 2010-2017.

8. Statistics Canada, CANSIM Table 401-0041: Domestic and international average air fares, by fare type group, 2010-2017; Statistics Canada, CANSIM Table 326-0020: Consumer Price Index, 2010-2017.

9. The drop has been 40% since 2013. Statistics Canada, CANSIM Table 329-0075: Industrial product price index, by North American Product Classification System (NAPCS), 2013-2016.

10. International Air Transport Association, “Airline Industry Economic Performance − 2018 Mid-year − Table,” June 4, 2018.

11. The lowering of restrictions to foreign investment favours the growth of the air transport sector, especially low-cost airlines. Christopher Findlay and David K. Round, “The ‘Three Pillars of Stagnation’: Challenges for Air Transport Reform,” World Trade Review, Vol. 5, No. 2, 2006, pp. 251-270; Jan Walulik, “At the Core of Airline Foreign Investment Restrictions: A Study of 121 Countries,” Transport Policy, Vol. 49, 2016, pp. 234-251.

12. Ross Marowits, “Ultra low-cost airline battle heats up as Canada Jetlines prepares to launch,” Financial Post, November 14, 2017; Greg Keenan, “Competition boosts WestJet CEO’s resolve to get Swoop off ground,” The Globe and Mail, April 16, 2018.

13. World Economic Forum, The Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report 2017: Paving the Way for a More Sustainable and Inclusive Future, April 2017, p. 121.

14. Index based on ticket taxes, airport fees, and value added taxes. International Air Transport Association, Publications, IATA Economics, Public Policy Issues, Value of Aviation − Country Reports, January 2017.

15. Cost per enplanement is defined as all landing fees, airside usage charges, fuel flowage fees, terminal rents and other airline payments to airports divided by enplaned passengers. Ben Cherniavsky and Mark Begert, The Scoop on Swoop: An Analysis of Canada’s ULCC Opportunity, Canada Research, Raymond James Ltd., January 15, 2018, p. 13.

16. Certain smaller airports nonetheless continue to receive subsidies. Transport Canada, Transportation in Canada 2016—Statistical Addendum, 2016, p. 66.

17. The NAS includes airports in Ottawa and in all provincial and territorial capitals, as well as airports with annual traffic of 200,000 passengers or more. See Transport Canada, National Airports Policy, The National Airports System, February 3, 2010.

18. Alexandre Moreau, “The Charges and Taxes That Undermine the Competitiveness of Canadian Airports,” Viewpoint, MEI, June 23, 2016; Government of Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2017: Volume II—Details of Expenses and Revenues, December 2017, p. 23.18.

19. This is the sum of the surpluses for the fiscal years from 2012-13 to 2016-17. Government of Canada, op. cit., endnote 18, Section 23 – Transport, Budgetary details by allotment, 2013-2014 to 2016-2017 editions.

20. Government of Canada, Excise Tax Act, Part II—Air Transportation Tax, Section 8 and Schedule I, Section 9.1, May 9, 2018.

21. The lower rate is for Quebec, while the higher is for British Columbia and includes the carbon tax. Excluding this carbon tax, Ontario has the highest rate. Revenue Québec, Fuel Taxes, Fuel Tax Rates; British Columbia Ministry of Finance, “Tax Rates on Fuels: Motor Fuel Tax Act and Carbon Tax Act,” Tax Bulletin, April 2018, p. 7; Ontario Ministry of Finance, Taxes and Charges, Gasoline Tax, January 12, 2018.

22. Transport Canada, op. cit., endnote 16, pp. 22 and 32-33.

23. Craig A. Gallet and Hristos Doucouliagos, “The Income Elasticity of Air Travel: A Meta-analysis,” Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 49, November 2014, pp. 141-155; Sarath Divisekera, “Interdependencies of Demand for International Air Transportation and International Tourism,” Tourism Economics, Vol. 22, No. 6, 2016, pp. 1191-1206.

24. Stacey Mumbower, Laurie A. Garrow, and Matthew J. Higgins, “Estimating Flight-level Price Elasticities Using Online Airline Data: A First Step toward Integrating Pricing, Demand, and Revenue Optimization,” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, Vol. 66, August 2014, pp. 196-212.

25. Michel Kelly-Gagnon, “Canada’s High Airfares and Passenger Leakage,” Viewpoint, MEI, March 2014.

26. Vijay Gill, Driven Away: Why More Canadians Are Choosing Cross Border Airports, Conference Board of Canada, October 2012, p. 24.

27. Jean-François Arvis and Ben Shepherd, “Measuring Connectivity in a Globally Networked Industry: The Case of Air Transport,” The World Economy, Vol. 39, No. 3, 2016, pp. 369-385.