Saint Göran: A Competitive Hospital in a Universal System

Quebec’s Health Minister recently gave an ultimatum to the province’s hospitals such that emergency room stays could no longer exceed 24 hours. While our health system has failed for years to significantly reduce wait times, the performance of a Swedish hospital (the Saint Göran, a Stockholm hospital funded by the government and run by Capio, a private multinational company) should inspire decision-makers within our health care system.

Media release: Emergency rooms: A Swedish hospital shows that long waits need not be the norm

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| Quebec can learn from Swedish hospital on wait times (Montreal Gazette, October 17, 2017)

Comment un hôpital suédois réduit le temps d’attente à l’urgence (The MEI’s Journal de Montréal blog, October 17, 2017) |

Interview (in French) with Patrick Déry (Sophie sans compromis, BLVD 102.1 FM) |

This Economic Note was prepared by Patrick Déry, Public Policy Analyst at the MEI, in collaboration with Jasmin Guénette, Vice President of Operations at the MEI. The MEI’s Health Care Series aims to examine the extent to which freedom of choice and private initiative lead to improvements in the quality and efficiency of health care services for all patients.

Quebec’s Health Minister recently gave an ultimatum to the province’s hospitals such that emergency room stays could no longer exceed 24 hours.(1) While our health system has failed for years to significantly reduce wait times, the performance of a Swedish hospital should inspire decision-makers within our health care system.

Saint Göran is a Stockholm hospital funded by the government and run by Capio, a private multinational company. It stands out from its peers on various performance indicators, including emergency room wait times and the satisfaction of its patients and staff, all while costing the government less than Stockholm’s public hospitals. What is the secret of its success, and what lessons can be drawn for Quebec?

The Swedish Recipe

In Sweden, as in Canada, the government finances the majority of care. When Swedish patients go to a health facility, they must provide their personal identification number, or personnummer, the equivalent of our social insurance number. The procedure is the same regardless of whether the facility is publicly or privately run.

Contrary to Quebec, a Swedish patient must pay a modest contribution from his or her pocket, capped at around $170 a year. This “copayment,” which is present in all health facilities financed by the government,(2) has no impact on the accessibility of care: The proportion of Swedish patients who had to forgo care for financial reasons is lower than for Quebec patients, according to the Commonwealth Fund.(3)

Indeed, the Swedish health care system distinguishes itself for its degree of equity and its health care outcomes. It also provides better access to care than Canada.(4) The case of Saint Göran thus shows how a privately run hospital can be integrated into a universal, single-payer system, whether in Sweden or, if we were willing to try it, in Canada.

The Capio Flavour

At the turn of the 21st century, the county of Stockholm decided to turn to private enterprise for the management of the Saint Göran hospital.(5) In addition to the significant latitude granted to all Swedish hospitals in terms of management,(6) Saint Göran has been infused with Capio’s culture. Its business model, essentially, is to provide patients with quality care and to do so efficiently in order to generate profits.

To achieve this objective, the company makes constant use of internal and external performance indicators, including those of the Stockholm County Council, the local authority responsible for funding health care in the Swedish capital region.

Capio’s obsession with care quality and optimization has led to substantial productivity gains at Saint Göran over the years. The company is so confident in its methods that in the last call for tenders, it offered its services to the county for 10% less remuneration compared to both its previous level and to the remuneration of comparable hospitals in Stockholm.(7)

This reduction of public funding has not led to any decrease in the number of patients treated. On the contrary, the Saint Göran emergency room, which saw some 35,000 patients pass through its doors fifteen years ago, treated more than 86,000 of them in 2016. The opening of a new, ultramodern emergency room is set to boost this figure to over 100,000.(8)

Along with its productivity gains, Saint Göran sets the pace for Stockholm’s other hospitals, and continues to raise the bar year after year on metrics that are key for patients: performance targets set by the local authority, treatment guarantees, and hospital-acquired infection rates, among others.(9) The publication of this data is a condition imposed by the Stockholm County Council, and it gives rise to some healthy competition among care providers, be they public or private.(10)

Real Emergencies

26 minutes to see a doctor

The Saint Göran emergency room is also significantly more efficient than that of other Stockholm hospitals. The median wait time to see a doctor there was 26 minutes in 2016. No Swedish hospital does better.(11)

In comparison, a patient admitted to a Quebec emergency room must wait over two hours and a quarter, on average, just to see a doctor.(12) Even accounting for the limitations of comparing a median with an average, Quebec remains light years away from Saint Göran’s level of efficiency.

Shorter hospital stays

At Saint Göran, the median duration of emergency room stays for all patients is 2.8 hours, which again is better than most of its peers in Stockholm. Just under a quarter of patients (23%) wait more than 4 hours in emergency.(13)

In Quebec, half of patients (51%) wait more than 4 hours, which corresponds approximately to the median.(14) However, there is an enormous gap be-tween the median duration of stays for ambulatory patients, namely those who are “able to walk” (3.2 hours), and stretcher patients, who represent a third of emergency room stays (9.5 hours). For the latter, the median wait can reach 15 or even 20 hours in Quebec’s large hospitals.(15)

8 hours at Saint Göran, 48 hours in Quebec

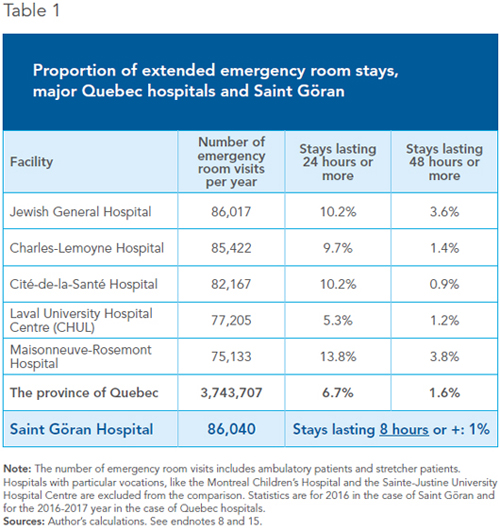

Interminable emergency room stays, which are frequent in Quebec and present to a certain degree elsewhere in Stockholm, are anecdotal at Saint Göran. Only 1% of its patients spend more than eight hours in emergency, versus from 7% to 14% in Stockholm’s main hospitals.(16) In Quebec, it is not uncommon for a patient to have to wait more than 24 hours—and sometimes more than 48 hours—on a stretcher before being admitted into a care unit.

The gap is even more striking when comparing Saint Göran with Quebec hospitals whose emergency rooms receive a similar volume of patients: The proportion of stays lasting more than 48 hours in Quebec is similar to that of stays lasting more than eight hours at Saint Göran (see Table 1).

One might think that Saint Göran enjoys conditions that are more favourable or that make any comparison with Quebec impossible. Yet the hospital receives its share of elderly clients: In 2016, one in six patients who visited the emergency room was over 80 years old.(17) Swedes also use their emergency rooms as much as Quebecers use theirs.(18)

Satisfied Patients, Happy Employees

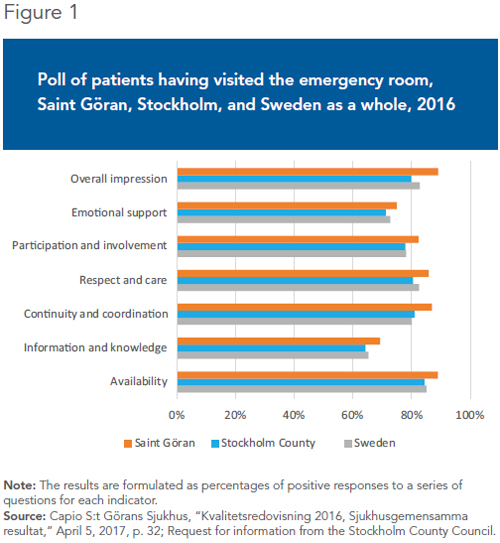

Saint Göran’s high degree of productivity has not been achieved at the expense of patients, since they judge that the quality of the care received is comparable or better than in Stockholm’s other hospitals(19) (see Figure 1). There is also less patient overcapacity, relative to what the emergency room can normally accommodate. As for Saint Göran’s employees, their degree of satisfaction is also higher than elsewhere in Stockholm, while the medical staff turnover rate and the number of sick days taken are lower.(20)

Staff involvement seems to contribute to this state of affairs. For example, triage is the responsibility of multidisciplinary teams, so that the patient’s condition can be evaluated quickly by experienced doctors and nurses. The method was put in place on the initiative of the employees themselves. Another factor that promotes efficiency is that emergency radiology is integrated into the emergency department. Finally, patients who are stable and whose diagnosis is clear can be admitted directly into dedicated care units, allowing them to be treated more quickly and “reducing the pressure on the emergency department.”(21)

It’s Not Magic, Just Economics

There is nothing magical or esoteric in Saint Göran’s results, merely the application of basic economic principles.

The first is that of decentralization. Instead of concentrating decisions within a central authority that is assumed to be omniscient, responsibility is entrusted to the administrators of different departments, and these in turn leave decisional latitude in the hands of those who are in contact with patients to manage and improve the daily operation of the hospital. Indeed, Capio makes it a point of pride to stipulate that the organization “is built from the bottom up and is organized around patient needs.”(22) In Quebec, many still believe that politicians and bureaucrats can micromanage an organization as complex as an entire health care system.(23)

The second principle is that everything is measured. In addition to the numerous indicators that come from the publication of hospital data, an annual poll conducted by the Stockholm County Council measures the degree of satisfaction of patients. This data, like much other data, is public. At Saint Göran, an annual poll was considered insufficient. A pilot project was thus put in place in a few departments to systematically collect the opinion of every patient at the moment of departure, the goal being to extend it to the entire hospital eventually.(24) In comparison, in Quebec, less than a quarter of hospitals poll their patients at least once a year.(25)

The third principle is the introduction of competition into the system. This encourages continual improvement by allowing different regions to implement different funding and care provision strategies, and allowing hospitals to compare themselves.(26)

The fourth is to have confidence in the initiative of private entrepreneurs who, motivated by profit, do not cut corners when it comes to patient care, but on the contrary, devote their efforts to treating them better and faster. This practice is good both for the profitability of the facility and for patients, who are back on their feet sooner and spend less time in the hospital.

According to a tenacious myth in Quebec that is maintained by many commentators, politicians and, unfortunately, too many doctors, making more room for private enterprise in the provision of care would threaten access and quality, and would happen at the expense of patients. The experience of Saint Göran shows that this is simply not the case.

From Monopoly to Competition

Saint Göran hospital is not a miracle solution, nor is it the only model. Besides Sweden, the health care systems of countries like Australia, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, just to name a few, have two things in common: They all rely on competition, and when it comes to access to care and equity, they all outperform Canada.(27)

There is no good reason to forgo the contribution of the competitive sector in the provision of hospital care, since this contribution in no way threatens the accessibility of care. It would in fact benefit the government, which could save money, as much as patients, who would be treated more quickly, and still without having to pay. The provincial governments could then decide, as the Stockholm County Council did, to entrust the administration of a hospital to a private operator, all while maintaining public funding as we know it.

The substantial decentralization of the management of the public system would also be welcome. Com-bined with the publication of performance indicators by facilities, this would undoubtedly lead to the spread of best practices and the general improvement of our health care system, which compares poorly with other industrialized countries in terms of access.

References

1. Aaron Derfel, “Barrette wields legal ultimatum to ER doctors to reduce overcrowding,” Montreal Gazette, August 23, 2017.

2. This contribution varies from 100 to 400 krona ($15 to $61) per consultation, and cannot exceed a total of 1,100 krona (around $167) per year. Sweden.se, Health Care in Sweden; 1177 Vårdguiden, Patientavgifter i Stockholms län; Bank of Canada, Currency Converter, 2017.

3. Health and Welfare Commissioner, Perceptions et expériences de la population : le Québec comparé—Résultats de l’enquête internationale sur les politiques de santé du Commonwealth Fund de 2016, 2017, p. 25.

4. Eric C. Schneider, Dana O. Sarnak, David Squires, Arnav Shah, and Michelle M. Doty, Mirror, Mirror 2017: International Comparison Reflects Flaws and Opportunities for Better U.S. Health Care, The Commonwealth Fund, July 2017, p. 5.

5. The mandate, granted in 1999, has since been renewed, and extended until 2021. Capio, Capio Annual Report 2016—The best achievable quality of life for every patient, 2017, p. 154.

6. The Swedish system is very decentralized, which allows local authorities to choose the funding method and the care providers in their region. This autonomy extends to hospitals, which are fully responsible for the management of care and staff, including doctors, whom they can hire and fire. See Jasmin Guénette, Johan Hjertqvist, and Germain Belzile, “Health Care in Sweden: Decentralized, Autonomous, Competitive, and Universal,” Viewpoint, MEI, June 2017.

7. Capio, Capio Annual Review 2013, 2014, pp. 3 and 32.

8. Capio S:t Görans Sjukhus, “Kvalitetsredovisning 2016, Sjukhusgemensamma resultat,” April 5, 2017, p. 20; Randeep Ramesh, “Private healthcare: the lessons from Sweden,” The Guardian, December 18, 2012; Capio, Capio Annual Report 2016, 2017, p. 54.

9. Capio, Capio Annual Report 2016, 2017, p. 57; Capio, Capio Annual Report 2015, 2016, pp. 38-39. Data confirmed by the Stockholm County Council.

10. LIR France, France Santé 2017 – Imaginons la santé, interview (in French) with Daniel Forslung of the Stockholm County Council, shared on YouTube, November 24, 2016. See especially between MIN 2 and MIN 5.

11. Socialstyrelsen, Väntetider och patientflöden på akutmottagningar – Rapport februari 2017, Stockholm läns landsting, February 2017, p. 74; Johan Ingero, Den förskräckliga succén – Historien om akutsjukhuset S:t Göran, Timbro, March 13, 2017.

12. Committee on Health and Social Services, L’étude des crédits 2017-2018 : Réponses aux questions particulières – Opposition officielle – volume 2, Quebec Department of Health and Social Services, Answer No. 179.

13. Socialstyrelsen, op. cit., endnote 11, pp. 65 and 72; Capio, Capio Annual Report 2016, 2017, p. 57; Stockholm County Council, request for information.

14. Canadian Institute for Health Information, Commonwealth Fund Survey 2016, Data Tables.

15. Request for access to information, September 2017. Ambulatory patients represent 67.78% of emergency room stays, and those on stretchers, 32.22%. Committee on Health and Social Services, L’étude des crédits 2017-2018 : Réponses aux questions particulières – Opposition officielle – volume 2, Quebec Department of Health and Social Services, Answer No. 178.

16. Capio S:t Görans Sjukhus, op. cit., endnote 8, p. 22.

17. Capio S:t Görans Sjukhus, op. cit., endnote 8, p. 21; Health and Welfare Commissioner, Apprendre des meilleurs : étude comparative des urgences du Québec, Government of Quebec, p. 5.

18. In 2016, in Sweden, 37% of patients had visited an emergency room over the past two years, versus 38% for Quebec. Health and Welfare Commissioner, op. cit., endnote 3, pp. 40 and 42.

19. Capio S:t Görans Sjukhus, op. cit., endnote 8, p. 32; Nationell Patientenkät, Akutmottagningar 2016; Request for information from the Stockholm County Council.

20. Hälso- och sjukvårdsförvaltningen, Benchmarking av akutsjukhusens effektivitet – Kärnverksamheterna på Danderyds sjukhus, Capio S:t Görans sjukhus och Södersjukhuset, Stockholm läns landsting, March 31, 2015, pp. 8, 31, and 32; Capio, Capio Annual Report 2016, 2017, p. 57; Capio, Capio Annual Report 2015, 2016, pp. 38-39. Data confirmed by the Stockholm County Council.

21. Capio, Capio Annual Review 2013, 2014, p. 33; Capio, Capio Annual Report 2016, 2017, p. 54.

22. Capio, Capio Annual Report 2015, 2016, pp. 10, 74, and 133; Capio, Capio Annual Report 2016, 2017, pp. 4, 14, 75, and 139.

23. Germain Belzile and Jasmin Guénette, “Centralized Health Care: A Recipe That’s Doomed to Fail,“ Viewpoint, MEI, July 13, 2017.

24. Capio, Capio Annual Report 2015, 2016, p. 36; LIR France, France Santé 2017 – Imaginons la santé, interview (in French) with Britta Wallgren, shared on YouTube, November 24, 2016.

25. Health and Welfare Commissioner, op. cit., endnote 17, p. 41.

26. Jasmin Guénette, Johan Hjertqvist, Germain Belzile, op. cit., endnote 6.

27. Eric C. Schneider, Dana O. Sarnak, David Squires, Arnav Shah, and Michelle M. Doty, op. cit., endnote 4, p. 5.