Viewpoint – To Stay Competitive, Canada Needs a Low, Proportional Corporate Tax Rate

U.S. President Donald Trump has just reiterated his intention to reduce the top federal corporate tax rate, aiming to lower it from 35% down to 20%. Such an abrupt reduction, or even a more modest one, would have serious consequences for the Canadian economy. Ottawa therefore has an interest in reforming its own corporate tax system without delay and in introducing proportional taxation based on the 10.5% rate that currently applies to small businesses, so that one single federal rate remains for all Canadian businesses.

Media release: Trump’s tax proposal: Ottawa should adopt a proportional tax rate of 10.5% to stay competitive

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| Pourquoi attendre la réforme fiscale de Trump? (La Presse+, September 28, 2017)

When it comes to corporate taxes, why wait for Trump? (The Globe and Mail, October 2, 2017) |

Interview with Mathieu Bédard (CTV News Montreal, CFCF-TV, October 2, 2017) |

This Viewpoint was prepared by Mathieu Bédard, Economist at the MEI. The MEI’s Taxation Series aims to shine a light on the fiscal policies of governments and to study their effect on economic growth and the standard of living of citizens.

U.S. President Donald Trump has just reiterated his intention to reduce the top federal corporate tax rate, aiming to lower it from 35% down to 20%.(1) Such an abrupt reduction, or even a more modest one, would have serious consequences for the Canadian economy. Ottawa therefore has an interest in reforming its own corporate tax system without delay and in introducing proportional taxation based on the 10.5% rate that currently applies to small businesses, so that one single federal rate remains for all Canadian businesses.

Canada’s Fiscal Competitiveness

In terms of how easy it is to conduct business, Canada tends to fare poorly compared to the United States. According to the World Bank, Canada is currently ranked 22nd worldwide, while the United States is ranked 8th. However, Canada outshines the United States in one key subcomponent of that index: Paying Taxes (17th versus 36th).(2)

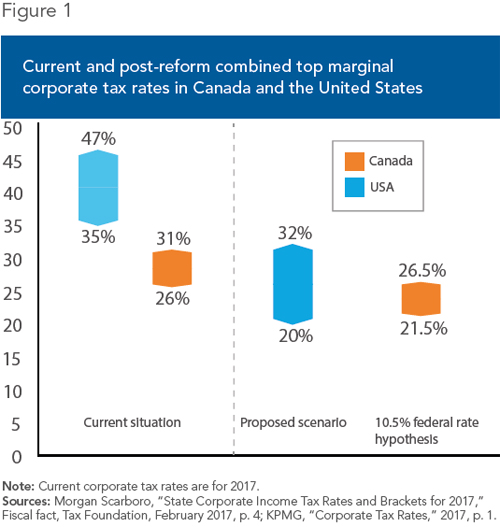

This advantage has been important in attracting investment to Canada in recent years. Presently, the federal corporate income tax rate is 15%. For those that request the small business deduction, a lower rate of 10.5% is applied to the first $500,000 of income.(3) Including the taxes levied by the provinces, the highest combined marginal corporate tax rate in Canada stands at 31%, which is below the lowest combined top rate (federal and state) for the United States at 35% (and well below the upper threshold of 47%).

However, as can be seen in Figure 1, the proposed U.S. reform would make Canada much less competitive in terms of taxation. Indeed, the new maximum rates that would apply to economically important states like Texas (20%) and Ohio (20%) would be well below the lowest marginal combined rate in Canada, currently at 26%, while in Michigan (26%) and New York (26.5%), for example, Canada’s advantage would disappear.(4)

Who Bears the Cost of High Tax Rates?

If such a reform were to be adopted in the United States, Canada’s fiscal competitiveness would be seriously undermined. The consequences would be borne in large part by workers. This is because workers are less mobile than capital, a difference that has become even more significant in recent decades as the mobility of capital has increased.(5)

A reduction in corporate tax rates in the United States would attract more capital there in search of higher relative returns. This means two things for workers. The first is that since capital is a complement to labour, there would be a reduction in the demand for labour in Canada, which in turn would depress wage growth. The second is that lower levels of investment reduce productivity growth, which would once again restrict wage growth.(6) As such, workers would bear a large share of the effects of Canada’s relatively higher corporate taxes.(7)

It is possible that the American President will not achieve all of his objectives in terms of reducing the tax burden. However, even a more modest reduction in tax rates in the United States would generate an effect similar to an increase in tax rates in Canada, since it would increase our relative tax burden. Canadian workers would therefore likely be the first to suffer the consequences of American tax cuts, were Ottawa to leave Canadian rates unchanged.

Benefits, With or Without American Reform

Indeed, even if American tax cuts do not materialize, the Canadian economy would still benefit from the adoption of a proportional corporate tax rate. This would have the effect of, among other things, encouraging business growth, since the existence of multiple (i.e., progressive) rates of taxation on corporate incomes represents a disincentive for firms to grow. Firms are also encouraged to legally divide their activities in order to reduce their tax burden, a bureaucratic waste of time and energy that could be put to productive use.(8)

In 2000, when the federal rate was much higher (28%),(9) 15% of companies filing as a “small business” limited their incomes to under $200,000 in order to be able to remain in this tax category. In 2009, after the federal rate had been reduced and the income threshold raised to $500,000, only 8.5% of companies limited their growth in this way.(10)

Of course, provincial governments account for a larger share of corporate taxes in Canada than state governments do in the United States. If combined with the federal measure described above, provincial efforts to lower their own rates would go even further toward preserving, and even increasing, Canada’s tax competitiveness.

It goes without saying that several elements of this proposal could bear further study, such as the sensitivity of investment to corporate taxes, especially in the case of small businesses, the effect of tax optimization strategies already put in place by many companies, or the effect of reduced tax revenue for the Canadian government.

But none of these nuances would change our central observation, which is that the maintenance of the current tax system, in the event of an American reform, would entail a loss of tax revenue when business investments—and the resulting earnings—cross the border.

By acting now, the Canadian government would be sending an unequivocal signal to companies that Canada is a good place to do business, and will continue to be a good place to do business, regardless of American reforms. This would maintain our tax competitiveness, in addition to being a great help to workers.

References

1. Sahil Kapur, “Trump planning on cuts for top earners: report,” Bloomberg, Financial Post, September 26, 2017.

2. The ranking is based on Toronto for Canada and New York City and Los Angeles for the United States. The Paying Taxes subcomponent “records the taxes and mandatory contributions that a medium-size company must pay in a given year as well as the administrative burden of paying taxes and contributions and complying with postfiling procedures.” The World Bank, Doing Business, Methodology.

3. Canada Revenue Agency, Corporation tax rates, February 7, 2017.

4. Tax Foundation, State Corporate Income Tax Rates and Brackets for 2017, February 27, 2017.

5. Won Yong Kim and Bang Nam Jeon, “Has International Capital Mobility Increased in Asia? Evidence from the Post-1997 Financial Crisis Period,” Contemporary Economic Policy, Vol. 31, No. 2, pp. 345-365; Julien Bengui, Enrique G. Mendoza, and Vincenzo Quadrini, “Capital Mobility and International Sharing of Cyclical Risk,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 60, No. 1, p. 42.

6. An American study covering the period from 1969 to 2012 found that each one-point increase in the corporate income tax rate reduces employment by 0.3%-0.5%, and income by 0.3%-0.6%. Alexander Ljungqvist and Michael Smolyansky, To Cut or Not to Cut? On the Impact of Corporate Taxes on Employment and Income, Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2016-006, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, December 11, 2015, p. 2.

7. Workers, who are often homeowners, would bear an additional burden, since a reduction in investments in Canada would exert downward pressure on real estate prices. This is a well-known phenomenon, documented notably in three exhaustive studies that looked into the cases of Europe, Germany, and the United States. These studies concluded that from 30% to 50% of a company’s fiscal burden was borne by workers, the rest being shared by firm owners and landowners. Wiji Arulampalam, Michael P. Devereux, and Giorgia Maffini, “The Direct Incidence of Corporate Income Tax on Wages,” European Economic Review, Vol. 56, No. 6, August 2012, pp. 1038-1054; Clemens Fuest, Andreas Peichl and Sebastian Siegloch, “Do Higher Corporate Taxes Reduce Wages? Micro Evidence from Germany,” American Economic Review, forthcoming; Juan Carlos Suárez Serrato and Owen Zidar, “Who Benefits from State Corporate Tax Cuts? A Local Labor Markets Approach with Heterogeneous Firms,” American Economic Review, Vol. 106, No. 9, September 2016, pp. 2582-2624.

8. Benjamin Dachis and John Lester, Small Business Preferences as a Barrier to Growth: Not So Tall After All, Commentary No. 426, C.D. Howe Institute, May 2015, pp. 12-13.

9. Brett Stuckey and Adriane Yong, “A Primer on Federal Corporate Taxes,” Library of Parliament Research Publications, International Affairs, Trade and Finance Division, June 16, 2011, pp. 1-9.

10. Benjamin Dachis and John Lester, op. cit., endnote 8; Kenneth Hendricks, Raphael Amit, and Diana Whistler, Business Taxation of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Canada, Technical Committee on Business Taxation, Working Paper No. 97-11, October 1997; Ajay Agrawal, Carlos Rosell, and Timothy S. Simcoe, Do Tax Credits Affect R&D Expenditures by Small Firms? Evidence from Canada, NBER, Working Paper No. 20615, October 2014.