Viewpoint – Housing Prices: Before Taxing Foreign Buyers, Scrap Rent Control

The government of Ontario has recently announced new policies intended to cool off its real estate market, imposing a 15% tax on foreign home buyers like the one enacted in 2016 in British Columbia, and also extending its rent control regulations. In Montreal, the opposition is asking the City to follow the example set by these two provinces. Quebec Finance Minister Carlos Leitão has said he is not interested in interfering with the market, and with good reason: This is precisely the kind of policy that contributes to the problem.

Media release: Taxing foreign buyers: British Columbia and Ontario should reconsider

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| Housing is best governed by the market (Montreal Gazette, June 6, 2017)

Le problème, c’est le contrôle des loyers (The MEI’s Journal de Montréal blog, June 6, 2017) |

Interview with Mathieu Bédard (Business in Vancouver, Roundhouse 98.3FM, June 7, 2017)

Interview with Mathieu Bédard (Tasha Kheiriddin, AM 640, June 7, 2017) |

Debate with Mathieu Bédard (Breakfast Television 7:30 am, CJNT, July 28, 2017) |

Viewpoint – Housing Prices: Before Taxing Foreign Buyers, Scrap Rent Control

The government of Ontario has recently announced new policies intended to cool off its real estate market, imposing a 15% tax on foreign home buyers like the one enacted in 2016 in British Columbia, and also extending its rent control regulations. In Montreal, the opposition is asking the City to follow the example set by these two provinces.(1) Quebec Finance Minister Carlos Leitão has said he is not interested in interfering with the market,(2) and with good reason: This is precisely the kind of policy that contributes to the problem.

In the Beginning, There Was Zoning

Housing prices have been high in cities like Toronto and Vancouver since long before current worries about foreign buyers.(3) In both places, zoning and land-use policies have been driving up real estate prices for more than fifty years.(4)

Economists and urbanists are well aware of the effects of zoning, land-use, and smart-growth policies, which have all been shown to restrict the availability of housing. When these policies become too restrictive, housing prices skyrocket and the burden falls disproportionately on the poorest, with fewer affordable housing units being built in favour of more luxurious housing units.(5) This gentrification phenomenon has been happening in Toronto, Vancouver, and Montreal for some time now.(6)

As for rent control, imposing limits on rent increases helps some people, to be sure, but it makes rental units less profitable for owners. Consequently, fewer are constructed, thus leading to higher rents for many other renters. Those who keep the same apartment for a long period of time can benefit, but for those who move into new apartments just being made available, prices are increasing faster than they otherwise would due to the artificially limited supply. Rent control thus actually exacerbates the underlying problem.

How to Destroy a City

Policies affecting housing can have an effect that’s far greater than most people would suspect. In a survey of economists of all backgrounds, 93% agreed that “a ceiling on rents reduces the quantity and quality of housing available.”(7) As Swedish economist Assar Lindbeck put it, “Next to bombing, rent control seems in many cases to be the most efficient technique so far known for destroying cities.”(8)

While actual “destruction” is hyperbolic, empirical research about the consequences that misguided housing policies can have is unequivocal. Metropolitan cities like New York are huge economic centres of activity, but much of the growth coming from these cities has been swallowed up by the high wages required to pay for the high rents caused in part by such policies. For instance, 12% of U.S. GDP growth is attributable to New York’s GDP growth. After housing costs are taken into account, however, this figure falls to less than 5%.(9)

It is not much of a stretch to imagine that a large portion of the productivity gains made in the Toronto and Vancouver areas (accounting for 18.6% and 7% of Canada’s GDP, respectively) must also have been siphoned off to fuel rising housing prices.(10)

Although Montreal has had its share of misguided housing policies, its housing market is by no means comparable to that of Toronto or Vancouver. While it’s arguable that foreign buying has had an impact on prices in the Vancouver area, the evidence is far less conclusive in Toronto. In Montreal’s case, that scapegoat cannot even be invoked, as such purchases represent less than 1% of transactions.(11) At any rate, a tax on foreign buyers is not a solution to our bad public policies.

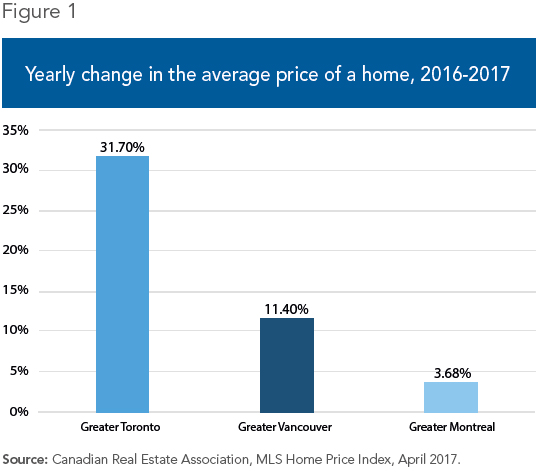

Montreal’s vacancy rate is also high and stable at 3.9%, compared to Toronto’s 1.3% and Vancouver’s 0.7%.(12) The year-over-year change in the price of a home reached 31.7% in the Greater Toronto Area and 11.4% in Greater Vancouver in April 2017 (see Figure 1). In the Greater Montreal Area, the corresponding figure was 3.7%.(13) If there’s a problem in Montreal, it’s the lack of investment in affordable housing which, again, is partly due to rent control.

Conclusion

Cities like Vancouver and Toronto would be expensive places to live even without misguided policies. Lots of people want to live in a big city, because these places tend to be economic juggernauts, full of opportunity. Yesterday’s distortionary policies have not only failed to address the matter; they have made things worse. Extending and expanding these measures will only pave the way for the same harmful consequences in the future.

Rather than letting artificially limited supply drive prices up and drive the poor away from cities, governments should allow the price mechanism to work, incentivizing developers to build more when prices go up. It would be better to target support for those who truly need it than to distort the market with well-intentioned but counterproductive measures.

This Viewpoint was prepared by Mathieu Bédard, Economist at the MEI. The MEI’s Regulation Series seeks to examine the often unintended consequences for individuals and businesses of various laws and rules, in contrast with their stated goals.

References

1. Pierre-André Normandin, “Immobilier : une taxe pour les acheteurs étrangers à Montréal?” La Presse, May 3, 2017; Opposition officielle à la Ville de Montréal, “Projet Montréal veut se doter d’outils pour lutter contre la spéculation immobilière étrangère,” News Wire, May 3, 2017.

2. La Presse canadienne, “Québec ne prévoit pas instaurer une taxe pour les acheteurs étrangers,” La Presse, June 2, 2017.

3. Felicity Stone, “Vancouver Real Estate Has Always Been Expensive—and We Have Proof,” BC Business, September 27, 2016.

4. In Vancouver, for example, zoning was introduced to Point Grey in 1922, and applied to the rest of the city when it merged in 1927, while zoning was introduced in Toronto in 1952. Robert L. Bish and Eric G. Clemens, Local Government in British Columbia, Union of British Columbia Municipalities, 4th edition, 2008; Joe D’Abramo, “Toronto Comprehensive Zoning By-law: The Art of Transition,” Ontario Planning Journal, Vol. 28, No. 2, March/April 2013, p. 7. For a description of the way zoning and land-use regulation has been distorting the housing market in Vancouver since the 1930s, see Jill Wade, Houses for All: The Struggle for Social Housing in Vancouver, 1919-50, University of British Columbia Press, January 1st, 1994, pp. 31-54.

5. Raven E. Saks, “Job Creation and Housing Construction: Constraints on Metropolitan Area Employment Growth,” Journal of Urban Economics, Vol. 64, No. 1, 2008, pp. 178-195; John M. Quigley and Steven Raphael, “Regulation and the High Cost of Housing in California,” American Economic Review, Vol. 95, No. 2, 2005, pp. 323-328; Edward L. Glaeser and Bryce A. Ward, “The Causes and Consequences of Land Use Regulation: Evidence from Greater Boston,” Journal of Urban Economics, Vol. 65, No. 3, 2009, pp. 265-278; Christopher J. Mayer and C. Tsuriel Somerville, “Land Use Regulation and New Construction,” Regional Science and Urban Economics, Vol. 30, No. 6, 2000, pp. 639-662; Edward L. Glaeser, Joseph Gyourko, and Raven E. Saks, “Why Is Manhattan So Expensive? Regulation and the Rise in Housing Prices,” Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 48, No. 2, 2005, pp. 331-369.

6. In fact, spontaneously occurring gentrification yields largely beneficial outcomes for everyone, including the poorest members of society; it is the artificial restriction of affordable housing that is harmful. See Vincent Geloso and Jasmin Guénette, “The Widespread Benefits of Gentrification,” Viewpoint, MEI, July 28, 2016.

7. Richard M. Alston, James R. Kearl, and Michael B. Vaughan, “Is There a Consensus among Economists in the 1990s?” The American Economic Review, Vol. 82, No. 2, February 1992, pp. 203-209.

8. Dan Selig, “Keeping Up,” Fortune, February 27, 1989, as quoted in United Nations and World Bank, “Natural Hazards, Unnatural Disasters: The Economics of Effective Prevention,” November 10, 2010, p. 213.

9. Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti, “Why Do Cities Matter? Local Growth and Aggregate Growth,” NBER, Working Paper No. 21154, May 2015, p. 2; Richard Florida, “The Urban Housing Crunch Costs the U.S. Economy about $1.6 Trillion a Year,” Citylab, May 18, 2015.

10. Mark Brown and Luke Rispoli, “Metropolitan Gross Domestic Product: Experimental Estimates, 2001 to 2009,” Statistics Canada, Economic Insights No. 42, November 10, 2014, p. 2.

11. Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, “Housing Market Insight, Montreal CMA,” July 2016.

12. Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, “Rental Market Report, Montreal CMA,” 2016; Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, “Rental Market Report, Greater Toronto Area,” 2016; Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, “Rental Market Report, Vancouver CMA,” 2016.

13. Canadian Real Estate Association, MLS Home Price Index, April 2017.