How Should Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability Be Defined?

Corporate social responsibility and sustainability are two widely used concepts. Corporate and government actions are partly judged according to them. Activists, politicians, and corporate leaders use them. But what exactly do they mean? Are they compatible with efficient management in a free society? To what extent are they even useful? This Economic Note will shed some light on these questions.

Media release: Corporate social responsibility and sustainability go hand in hand with the profit motive

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

|

Devrait-on limiter la recherche du profit des entreprises? (Le Devoir, January 30, 2017)

Right-sizing corporate social responsibility (National Post, February 3, 2017) |

How Should Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability Be Defined?

Corporate social responsibility and sustainability are two widely used concepts. Corporate and government actions are partly judged according to them. Activists, politicians, and corporate leaders use them. But what exactly do they mean? Are they compatible with efficient management in a free society? To what extent are they even useful? This Economic Note will shed some light on these questions.

Corporate Social Responsibility

The concept of corporate social responsibility has been defined in various ways. The first modern mention that launched the contemporary literature on this topic was in a book published by American economist Howard R. Bowen in 1953, Social Responsibilities of the Businessman. He defined it as “the obligations of businessmen to pursue those policies, to make those decisions, or to follow those lines of action which are desirable in terms of the objectives and values of our society.”

A more expansive definition would include further actions to promote socially desirable outcomes such as protecting the environment, above and beyond what is expected in the more neutral definition. If the main goal of a firm is still to maximize profits, then taking further steps toward the “social good” can improve the bottom line insofar as they lead to increased sales through a better image and reputation, reduced costs through decreased resource use, better employee engagement through intra-firm “green” activities, more social licence coming from a better perception of the firm, etc.

Such definitions of corporate social responsibility do not lead to harmful consequences and can be embraced by corporations without creating any problems.

Some people wish to go even further, however, by imposing on firms a definition of social responsibility that extends beyond the constraints already found in laws and regulations. This implies maximizing the welfare of all “stakeholders,” including workers, consumers, the wider community, and future generations. This more extreme definition is much more problematic for shareholders, and for society in general.

Milton Friedman, the 1976 economics Nobel laureate, famously argued against a more expansive kind of social responsibility, writing that “there is one and only one social responsibility of business—to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition, without deception or fraud.”(1) As we have known since Adam Smith, this will lead to a general increase in society’s welfare, without it being a direct goal of the profitable activity. The danger of diverting business from its pursuit of profit is the slowing, or even the reversal, of this increasing welfare.

Is corporate social responsibility profitable or costly for a business? Can a firm “do well while doing good”? The answer depends on the sorts of activities being considered.

Corporations, in order to survive and thrive, must respond to their clients’ preferences. If certain forms of social responsibility are profitable for the businesses that implement them (leading to more engaged employees, better risk management, more satisfied clients), these practices will tend to spread by themselves thanks to the profit motive. On the other hand, if a firm cheats its clients, it won’t stay in business very long, as they will soon look for an alternative supplier.

But what about the sorts of practices that reduce efficiency, and that well-intentioned social responsibility agents often try to push within their companies? If they are implemented, shareholders, consumers, or employees will have to pay the cost in terms of reduced profits, higher prices, or lower wages.

Trying to regulate firms internally through aggressive social responsibility is much less efficient than having a government regulate activities (or simply allowing the market to do so). Think of the concrete example of working conditions. Trying to push companies to increase wages and other worker benefits (such as more vacation time or free daycare) above what is already determined by government regulations and market conditions will increase costs and have adverse effects on the competitiveness of the firm, and might even endanger its existence.

Why, then, do some push for an aggressive form of corporate social responsibility? Probably because they are unable to get their way in the political arena, either because their goals are unpopular in themselves, or because they are just too costly.

In short, corporate social responsibility, if interpreted narrowly, is neither a threat nor a panacea. If it is taken to extremes, it can distract companies from what they do best, which is to produce the goods and services that customers want at the lowest cost. It cannot and should not replace market discipline and government regulations.

Sustainability

Another widely used but loosely defined term is the concept of sustainability, which dates back to the 1960s and early 1970s.(2) Several books published around that time warned of impending disasters if humanity did not mend its ways. In her influential 1962 book, Rachel Carson(3) predicted that very soon, spring would be silent, with no birds chirping nor insects buzzing. In 1968, the famous environmentalist Paul Ehrlich(4) predicted widespread famines in the near future, including in Europe and in North America. The Club of Rome(5) announced in 1972 a coming worldwide depletion of basic resources, including metals and energy, as well as a global economic collapse.

These environmental scares did not materialize, but they did create movements dedicated to sustainability.

The basic idea behind sustainability deals with an important notion: that the multitude of individual choices must take into account the scarcity of resources. In other words, sustainability must be feasible from an economic viewpoint.(6)

Like corporate social responsibility, sustainability makes sense if we define it in a narrow way. In 1986, for instance, the Brundtland Report defined sustainable development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”(7)

More recently, however, the United Nations produced a list of 17 Sustainable Development Goals, adopted in 2015, that have stretched the concept far beyond the intents of the original environmentalist thinkers. These include practically any proposal deemed good, such as to “[e]nsure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages” (goal 3). The UN resolution states that “[s]port is also an important enabler of sustainable development.”(8)

UNESCO, itself a part of the UN, views culture as part of sustainable development.(9) And such a broad conception of “sustainability” is inevitably accompanied by calls for all sorts of government intervention. It is even used to argue for a guaranteed minimum income.(10)

Yet if sustainability means “whatever is good in terms of humanity’s and our planet’s future welfare,” it is not a very useful concept. Not everything can be done and not all goals can be attained. Trade-offs must be made. One cannot at the same time restrict growth, help the poor, and maintain the productive incentives of the non-poor.

If we adopt a narrower definition, then making sure pollution is limited and that we don’t run out of resources can remain the focus of sustainability. And in fact, markets are an ideal institution for ensuring sustainability thus defined.

First of all, they signal problems with resource scarcity, through higher prices. Whenever increased scarcity drives prices up, everyone adjusts by using less, substituting more abundant alternatives.

Second, a scarcer and costlier resource creates an incentive to find more. Copper is a good example, as reserves soared and prices plummeted over the past 200 years.(11) Just from 1995 to 2015, world conventional copper reserves more than doubled, from 310 Mt to 720 Mt.(12)

Third, since innovation to replace scarce resources can be very profitable, a free enterprise system usually takes care of shortages before they ever happen. Copper is again a good example, as the need for this metal in telephone lines more or less melted away with the invention of optic fibre and cell phones. In fact, the world has never run out of a resource critical for growth. Using regulation to restrict current growth for the purpose of ensuring that resources can be used by future generations is therefore unnecessary.

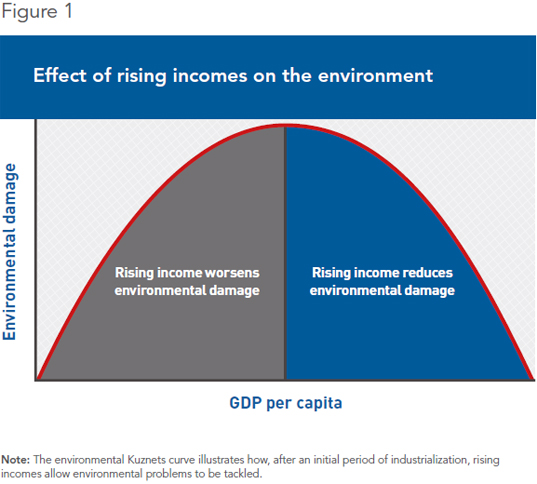

Finally, a free-market system promotes growth, rising living standards, and a cleaner environment.(13) Almost all the richest countries (in real GDP per capita) are ones in which economic freedom is high, and a richer society is one that can take the environment seriously and tackle any problems that arise, as illustrated in Figure 1.(14) According to the Environmental Performance Index from Yale University’s Center for Environmental Law and Policy, rich countries’ environments are in much better shape than those of developing countries.(15)

Conclusion

Corporate social responsibility and sustainability are important concepts. However, understood too expansively, they can cause significant harm to businesses and our economy. Giving them a very concrete and operational meaning is essential. Corporate social responsibility should mean running a firm in a legal and responsible way. Sustainability should mean making sure our society does not run out of resources and that pollution is controlled.

Properly understood, these two operational concepts complement rather than oppose the profit motive, within a context of respect for society’s laws and regulations and reliance on the market price mechanism. They can help firms and society achieve a goal that everyone shares: a better life, now and in the future. (Table 1)

This Economic Note was prepared by Germain Belzile, Senior Associate Researcher at the MEI, in collaboration with Michel Kelly-Gagnon, President and CEO of the MEI.

References

1. Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom, University of Chicago Press, 1982, p. 112.

2. Edward B. Barbier, “The Concept of Sustainable Economic Development,” Environmental Conservation, Vol. 14, No. 2, July 1987, p. 102.

3. Rachel Carson, Silent Spring, Houghton Mifflin Company, Anniversary edition, 2002.

4. Paul R. Ehrlich, The Population Bomb, Sierra Club, 1968; Pierre Lemieux, “Running Out of Everything,” Library of Law and Liberty, June 3, 2014.

5. Donella H. Meadows et al., The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind, Universe Books, 1972.

6. Lawrence Reed Watson, “Enviropreneurship in Action,” in Terry L. Anderson and Donald R. Leal, Free Market Environmentalism for the Next Generation, Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

7. World Commission on Environment and Development, Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future, Transmitted to the General Assembly of the United Nations, 1987, p. 41.

8. United Nations General Assembly, Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, October 21, 2015, pp. 10 and 16.

9. UNESCO, Culture for Sustainable Development.

10. Wouter Achterberg, “From Sustainability to Basic Income,” in Michael Kenny and James Meadowcroft (eds.), Planning Sustainability, Routledge, 1999, pp. 128-147.

11. Bjorn Lomborg, The Skeptical Environmentalist: Measuring the Real State of the World, Cambridge University Press, 2001, Figure 79.

12. USGS, National Minerals Information Center, Copper, Statistics and Information, 2016.

13. Johan Norberg, In Defense of Global Capitalism, Cato Institute, 2003, pp. 63-104.

14. Tom Murphy, “Air pollution is deadly and hurts the world’s poor the most,” Humanosphere, May 16, 2016. To learn more about the environmental Kuznets curve, shown in Figure 1, see Matt Welch, “Capitalism Makes You Cleaner,” Reason, October 2015.

15. Environmental Performance Index, Global Metrics for the Environment: The Environmental Performance Index Ranks Countries’ Performance on High-Priority Environmental Issues—2016 Report, Yale University, 2016, pp. 18-19.