Which Is the Greater Threat to Privacy, Business or Government?

In the debate over the collection, sharing, and use of personal information, there exists a widespread prejudice according to which companies are less respectful of citizens’ privacy than governments are. Yet companies universally operate by means of mutual consent, whereas governments very rarely ask those concerned for permission to access their information. With the Office of the Privacy Commissioner calling for the modernization of the laws governing the practices of the federal government and of companies, it is important to highlight the fundamental differences between the two, as well as the real source of danger.

Media release: How far does secret government surveillance go?

Links of interest

Links of interest

|

|

|

|

Surveillance et menace réelle à nos droits (Le Soleil, November 14, 2016)

Big brother sleeps easy (National Post, November 23, 2016) |

Interview (in French) with Mathieu Bédard (Duhaime-Drainville le midi, FM93, November 8, 2016)

Interview (in French) with Mathieu Bédard (Martineau-Trudeau, CHOI-FM, November 8, 2016) |

Interview (in French) with Mathieu Bédard (Mario Dumont, LCN, November 8, 2016)

Interview with Mathieu Bédard (CTV News Montreal, CFCF-TV, November 24, 2016) |

Which Is the Greater Threat to Privacy, Business or Government?

In the debate over the collection, sharing, and use of personal information, there exists a widespread prejudice according to which companies are less respectful of citizens’ privacy than governments are. Yet companies universally operate by means of mutual consent, whereas governments very rarely ask those concerned for permission to access their information. With the Office of the Privacy Commissioner calling for the modernization of the laws governing the practices of the federal government and of companies,(1) it is important to highlight the fundamental differences between the two, as well as the real source of danger.

The Collection of Public Information

It is not easy to delineate the boundaries of privacy, since they vary enormously from person to person. For example, many people refuse to share their medical information with anyone other than their doctor and immediate family, while others will appear on television to discuss their illness and thereby help those who are in the same situation. Respect for privacy must therefore be seen not as an absolute and uniform level of secrecy, but rather as a level of control that individuals have over information that concerns them.(2)

Appropriate public policies help maintain this control by forcing companies and governments to be transparent and to respect their commitments regarding the use of personal information. Not all methods of collecting personal information have the same consequences for privacy, however.

When information is already public, the principle of consent very often does not apply. For example, private companies collect information about us without our prior approval from archives and other public sources like search engines.

This practice can have numerous beneficial and legitimate uses. This information allows the media to investigate and denounce certain reprehensible acts, for instance. A chance Internet search led a French woman to discover that her spouse was infected with AIDS and had been convicted of having knowingly infected several women.(3) Preventing the collection of such information, for example through the creation of a “right to be forgotten” as exists in Europe, would make it easier for ill-intentioned people to shirk their responsibilities and for criminals to reoffend.

Similarly, credit reporting agencies use public archives and search engines to complete the data that their clients already consent to divulge through their financial institutions. This allows them to preserve the good credit ratings of many people, all while protecting lenders and landlords.

As long as organizations that engage in these practices are transparent and allow those concerned to have access to the information compiled and allow them the chance to correct errors, this is compatible with respect for privacy.(4) The government, unlike companies, usually does not respect these conditions.

A Vast System of Privacy Violation

According to the Office of the Privacy Commissioner, “the federal appetite for our information has grown in direct proportion to the ease with which that information can be collected.”(5)

Indeed, just as new technologies were taking off, a privacy violation system was being set up, unbeknownst to the public, of a magnitude that no one could suspect, which was revealed in June 2013 by the whistleblower Edward Snowden. Telephone calls, emails, video conferences, social networks… practically all online communications are now intercepted by governments.(6)

Even though Edward Snowden’s revelations concern the American government in particular, Canadians are also targeted by this system. For one thing, the Internet and telecommunications know no borders, and Canadians also use these means of communication. For another, most governments around the world, including Canada, have similar surveillance programs or collaborate with the American program.(7) Even at the provincial level, the Sûreté du Québec recently announced the creation of such a program.(8)

Journalists have thus discovered that the Royal Canadian Mounted Police had access to the private, encrypted communications of most BlackBerry smartphones, and had decrypted approximately a million private messages.(9)

We do not know the scope of these surveillance programs. We do know that the number of calls and communications intercepted was multiplied by 26 in 2015, however, without the authorities revealing any reasons for this.(10) Several experts strongly suspect that the Canadian government uses instruments that capture the calls and messages of all mobile devices in an area, and not only those of people under surveillance.(11) These suspicions come up against the government’s lack of transparency.

Furthermore, governments force companies to spy for them. Many companies have been pressured by the authorities, in Canada and in the United States, to share private information and data. The responsibility for this privacy violation rests squarely on the government, since it leaves them no choice.(12)

These programs represent a threat to individual privacy, but this is not the only type of threat. As shown by the recent revelations concerning the police surveillance of journalists in Quebec, the threat also extends to the media.(13) Moreover, industrial espionage, practised by governments but also by hackers having gotten their hands on governments’ espionage tools, represents a real risk for companies.(14)

The Fundamental Differences between Governments and Companies

The approaches of companies and of government agencies when it comes to respect for privacy are totally different. In the American system, as in the Canadian and European systems, companies must inform the people they have dealings with of the ways in which their information will be used, and ask for their explicit consent.(15) Governments, on the contrary, use collection methods and other practices that ignore the principle of consent and are often secret.

Another important difference is that individuals’ interactions with companies can be avoided relatively easily. It is always possible not to use a smartphone, not to join social networks, or to use cash rather than a credit card in order to avoid sharing personal data, even if in doing so we forego numerous benefits and advantages associated with modernity.

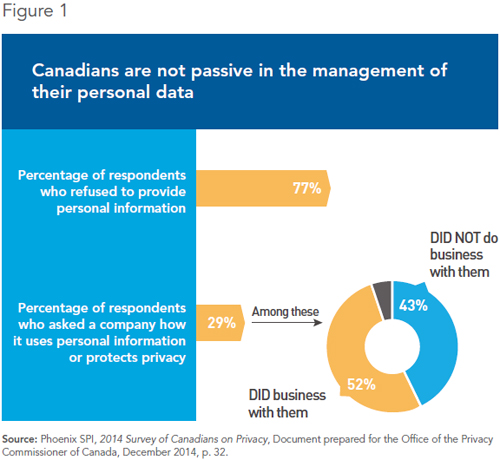

Polls show that Canadians are not passive in managing their personal information. They inform themselves regarding the use of their data by companies, and when the answers are not to their liking, they refuse to do business with them (see Figure 1).

Governments do not give citizens the same level of control over their personal information as companies give them. This is first of all because in many cases, the sharing of information is mandatory, often for obvious reasons. This is the case for income tax returns, land registries, driver’s licences, criminal records, historical use of various social programs, etc. But it is also because they do not have the same safeguards against abuses that companies have.

The first safeguard stems from the fact that companies are in competition with one another, and as a result, they must give customers what they want. Changes due to consumer pressure are frequent. One need only think of the cancellation of Facebook Beacon and Google Buzz, or of the changes made to the way in which geolocation is stored on Apple devices.(16)

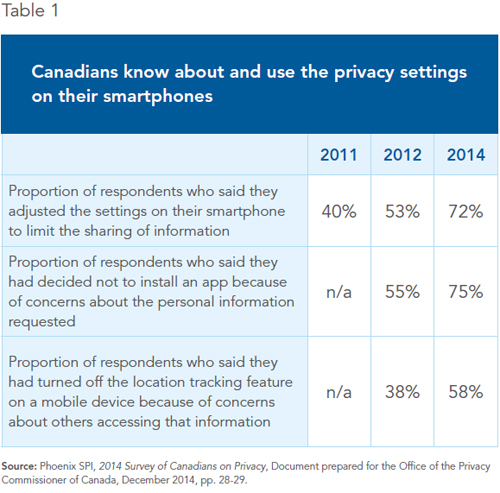

Moreover, with each new version of their operating systems, the two main types of smartphones have privacy settings that are more and more fine-grained and adaptable to individual users’ personal limits. The results of a poll commissioned by the Office of the Privacy Commissioner shows that Canadians are aware of the existence of these parameters and use them (see Table 1).

Another safeguard exists in the case of the private sector: the fact that the personal data collected by big Internet companies is too precious to be sold.(17) Indeed, the targeted advertising made possible by this information represents a value of up to US$1,200 per user, versus as little as half a cent per user if the information was sold. Preserving exclusive access to this information in order to target advertising is thus much more profitable than selling it.

In the case of governments, there are few safeguards. Even the revelations of Edward Snowden and the indignation of the international community have not led to any substantial changes in the data collection policy of the United States. Just recently again, it was revealed that the American government was asking Yahoo to intercept all incoming emails, a measure that President Obama and an NSA oversight board had sworn that the government was not using.(18)

Modernizing the Laws

The prevention of terrorism and criminality are obviously legitimate objectives. The government has armed itself with tough laws to fight terrorism, and as a result spies on private communications in collaboration with foreign governments to thwart attempted attacks. However, it must be recognized that these are exceptional circumstances. These powers must be properly regulated, limited to these objectives, and not trivialized.

This is unfortunately not what is happening. It is alarming to see that the limits imposed on these surveillance agencies by the Canadian government are unclear, especially when it comes to sharing databases between government agencies and with foreign governments.(19) A recent Federal Court ruling revealed that the Canadian Security Intelligence Service had acted illegally by conserving personal data for 10 years.(20) Ottawa imposes much stricter rules on the private sector than it imposes on itself regarding the collection, use, communication, and conserving of personal information, as recognized by the Office of the Privacy Commissioner and other observers.(21)

If the government were to modernize privacy protection laws, it should first of all target the two main threats to privacy in Canada: government practices that limit individuals’ control over their own sharing of information, and the lack of transparency that characterizes the collection and sharing of data by government agencies. The “Big Brother” threatening privacy in Canada is not a company, but the government itself.

This Economic Note was prepared by Mathieu Bédard, Economist at the MEI. He holds a PhD in economics from Aix-Marseille University, and a master’s degree in economic analysis of institutions from Paul Cézanne University.

References

1. Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, 2015-2016 Annual Report to Parliament: Time to Modernize 20th Century Tools, 2015-2016 Annual Report to Parliament on the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act and the Privacy Act, September 27, 2016.

2. Jim Harper, Understanding Privacy—and the Real Threats to It, Policy Analysis, Cato Institute, August 4, 2004.

3. Marine Messina, “Douze ans de prison pour avoir transmis le virus du sida à sa compagne,” Le Monde, October 2, 2014.

4. Data brokers, which are companies that collect personal information on consumers from various public and non-public sources and resell it to other companies, sometimes disregard the consent and transparency that are required to respect privacy. The nature and magnitude of this phenomenon remain unclear, however. For more details, see Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, Data Brokers: A Look at the Canadian and American Landscape, Report prepared by the Research Group of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, September 2014.

5. Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, op. cit., endnote 1, p. 11.

6. Glenn Greenwald, “NSA collecting phone records of millions of Verizon customers daily,” The Guardian, June 6, 2013; Glenn Greenwald, “XKeyscore: NSA tool collects ‘nearly everything a user does on the internet’,” The Guardian, July 31, 2013.

7. Colin Freeze, “Data-collection program got green light from MacKay in 2011,” The Globe and Mail, June 10, 2013; Greg Weston, Glenn Greenwald, and Ryan Gallagher, “Snowden Document Shows Canada Set up Spy Posts for NSA,” CBC News, December 9, 2013.

8. Vincent Larouche, “La SQ met sur pied un grand centre de ‘cybersurveillance’,” La Presse, November 1st, 2016.

9. Justin Ling and Jordan Pearson, “Exclusive: Canadian Police Obtained BlackBerry’s Global Decryption Key,” Vice News, April 14, 2016.

10. Ian MacLeod, “Federal spies suddenly intercepting 26 times more Canadian phone calls and communications,” National Post, August 24, 2016.

11. Matthew Braga, “Why Canada isn’t having a policy debate over encryption,” The Globe and Mail, February 23, 2016; Matthew Braga, “The covert cellphone tracking tech the RCMP and CSIS won’t talk about,” The Globe and Mail, September 15, 2014.

12. In the United States, the process for forcing a company to cooperate includes the sending of a National Security Letter. This is a letter which the recipient cannot talk about with anyone and which is very difficult to contest in court, as shown by the story of the founder of the encrypted email service Lavabit, Ladar Levison, in which the courts ensured through controversial legal proceedings that his case would never be heard. To give a sense of the number of such letters, Google receives between one and 999 each half-year. Canada is even less transparent since we do not even know the directives that govern this kind of surveillance. Ladar Levison, “Secrets, lies and Snowden’s email: why I was forced to shut down Lavabit,” The Guardian, May 20, 2014; Google, Transparency Report, United States.

13. Philippe Teisceira-Lessard, “Patrick Lagacé visé par 24 mandats de surveillance policière,” La Presse, October 31, 2016; Vincent Larouche and Philippe Teisceira-Lessard, “Six journalistes épiés par la Sûreté du Québec,” La Presse, November 2, 2016.

14. Such a scenario took place this past August, when hacking software belonging to the National Security Agency was stolen and leaked. Hackers then almost immediately used this leak to infiltrate companies’ computer systems. This risk also exists in Canada, endangering privacy and trade secrets. Lily Hay Newman, “Of course everyone’s already using the leaked NSA exploits,” Wired, August 24, 2016.

15. The Law Library of Congress, Online Privacy Law: the European Union, Global Legal Research Center, June 2012 (updated in May 2014); Government of Canada, Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act, June 2015; Practical Law, Data protection in United States: Overview.

16. Louise Story and Brad Stone, “Facebook Retreats on Online Tracking,” The New York Times, November 30, 2007; Joseph Tartakoff, “Google fixes privacy issues in Buzz,” The Guardian, February 15, 2010; Marguerite Reardon, “Apple: We’ll fix iPhone tracking ‘bug’,” Cnet, April 27, 2011.

17. Alexis C. Madrigal, “How Much Is Your Data Worth? Mmm, Somewhere Between Half a Cent and $1,200,” The Atlantic, March 19, 2012.

18. Joseph Menn, “Exclusive: Yahoo secretly scanned customer emails for U.S. intelligence – sources,” Reuters, October 4, 2016; Kate Connolly, “Barack Obama: NSA is not rifling through ordinary people’s emails,” The Guardian, June 19, 2013; Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board, Report on the Surveillance Program Operated Pursuant to Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, Government of the United States, July 2, 2014, pp. 1 and 8.

19. Justin Ling, “Secret Documents Reveal Canada’s Spy Agencies Got Extremely Cozy With Each Other,” Vice News, May 20, 2015.

20. Colin Freeze, “In scathing ruling, Federal Court says CSIS bulk data collection illegal,” The Globe and Mail, November 3, 2016.

21. Daniel Therrien, “Bringing Privacy Protection into the 21st Century,” Policy Options, October 5, 2016; Jennifer Stoddart, Appearance before the Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics on Privacy Act Reform; David H. Flaherty, Reflections on Reform of the Federal Privacy Act, June 2008; Colin Freeze, “Watchdog warned of CSIS data access,” The Globe and Mail, June 19, 2013.