Viewpoint – Do Low Interest Rates Justify Deeper Deficits?

The federal deficit is rising, far beyond the $10 billion projected in the Liberal platform. It is widely repeated that now is a good time to borrow since interest rates are very low. Those who use this argument to justify borrowing forget that interest charges are not the only cost associated with deficits. This Viewpoint presents five alternative ways of thinking about the cost of deficits and infrastructure spending.

Links of interest

Media release: Money doesn’t grow on trees, even for the federal government

* * *

Viewpoint – Do Low Interest Rates Justify Deeper Deficits?

The federal deficit is rising, far beyond the $10 billion projected in the Liberal platform. The 2016-2017 budget fixed it at $29.4 billion, and it is expected that the November 1st budget update will raise it again substantially. The stated purpose is to stimulate the Canadian economy, whose prospects for growth are deteriorating.(1)

It is widely repeated that now is a good time to borrow since interest rates are very low. Those who use this argument to justify borrowing forget that interest charges are not the only cost associated with deficits. This Viewpoint presents five alternative ways of thinking about the cost of deficits and infrastructure spending.

1. Future Interest Rates

Public debts are rarely reimbursed. A substantial portion must be refinanced each year at the new interest rates. This year, for example, the government will not just borrow the equivalent of its deficit, but a total of $278 billion.(2)

When thinking about the cost of borrowing, one must therefore take into account not only current interest rates, but also future interest rates. There is no guarantee that they will stay at this extremely low level for very long, and a sudden hike could raise public debt charges.

2. The Cost of Taxes

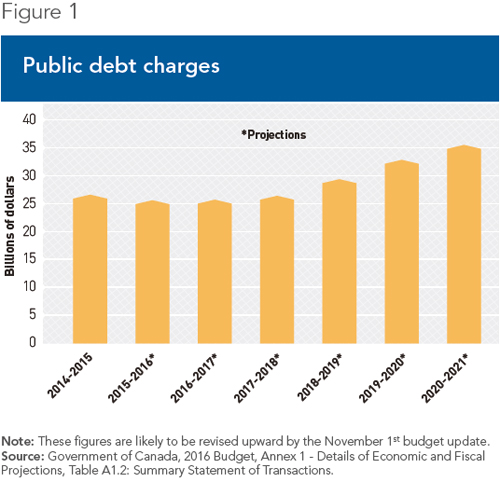

Public debt charges represent $25.7 billion this year, or 8.7% of the federal government’s budget.(3) Figure 1 projects the evolution of these charges up until 2020-2021. Even when interest rates are low and capital is not reimbursed, these charges must be paid with taxes.

These taxes have an adverse effect on the economy since they create distortions in the private sector, reduce purchasing power, and discourage productive activities. This is what is referred to as the deadweight loss of taxation, which is to say that beyond a certain level, tax increases entail a loss of economic well-being that outweighs the increase in well-being financed by the government’s additional revenues.

Recent studies vary, estimating that each dollar of taxes collected costs society more than $1.10, and up to $5.00 in certain cases.(4) Since the weight of taxation must be added to public debt charges, public debt ends up being quite expensive, even when interest rates are very low.

3. The Cost of Infrastructure Maintenance

Those who are calling for massive investments in new infrastructure often forget to specify that once this infrastructure is built, it must be maintained. According to a House of Commons report, “a significant and predictable proportion—up to 80% for some projects—of the overall costs over the life cycle of an infrastructure project is O&M [i.e., operations and maintenance].”(5)

4. The Opportunity Cost(6)

When certain resources in a society are redirected toward government projects, this necessarily means that fewer resources are available for private investments. This is referred to as the opportunity cost: that which must be forgone so that this spending can occur.

In order to quantify the opportunity cost of this infrastructure spending, we use the average rate of return on capital, which indicates the profitability of private projects. In Canada, the average over the past 15 years is 7.1%.(7)

In order to be valid as a measure of the cost of government borrowing, this opportunity cost must also take into account the investment’s associated risk, as well as its irreversibility. Indeed, contrary to many private investments, what the government owns generally cannot be resold.

It can be estimated that these factors push the opportunity cost of government spending on infrastructure to around 10% even if interest rates are zero. This is a very prudent estimate.(8)

5. More expensive public sector pensions

Low interest rates also have the effect of making the performance objectives of public sector pension programs more difficult to attain. A recent analysis based on data from the Finance Department notes that currently low interest rates entail additional costs of $3 billion a year, erasing a large part of the savings registered by the government thanks to lower public debt charges.(9) With such increases in pension plan liabilities, the government is already further in debt, before even borrowing an extra dime.

Conclusion

All of these arguments challenge the popular belief that when interest rates are low, the government should take advantage of the opportunity to borrow. There is a crucial distinction that must be understood between the interest rate at which the government borrows and the cost for society as a whole. As Ottawa prepares to depart even more drastically from its initial projections in its budget update, it should be remembered that money does not grow on trees, even for the government.

This Viewpoint was prepared by Mathieu Bédard, Economist at the MEI. He holds a PhD in economics from Aix-Marseille University, and a master’s degree in economic analysis of institutions from Paul Cézanne University. The MEI’s Taxation Series aims to shine a light on the fiscal policies of governments and to study their effect on economic growth and the standard of living of citizens.

References

1. The Bank of Canada, for example, has lowered its growth forecast for Canadian GDP for 2016, from 1.3% in July to 1.1% in October. Bank of Canada, Monetary Policy Report, October 2016, p. 7.

2. In addition to the government’s financial requirements, which amount to $37 billion, this year, the Finance Department of Canada will refinance $241 billion of bonds and Treasury bills coming due on a gross debt of approximately $932 billion. Government of Canada, 2016 Budget, Annex 3 – Debt Management Strategy for 2016–17, Sources of Borrowings.

3. Government of Canada, 2016 Budget, Annex 1 – Details of Economic and Fiscal Projections, Table A1.2: Summary Statement of Transactions.

4. Mathieu Bédard, “The Federal Government’s Deficits Will Not Stimulate the Canadian Economy,” Viewpoint, MEI, March 10, 2016.

5. House of Commons, Updating Infrastructure in Canada: An Examination of Needs and Investments, Report of the Standing Committee on Transport, Infrastructure and Communities, June 2015, p. 9.

6. This methodology is inspired by Tyler Cowen, “What is the opportunity cost of additional government borrowing?” Marginal Revolution, August 12, 2016.

7. Statistics Canada, CANSIM Table 180-0003: Financial and taxation statistics for enterprises, by North American Industry Classification System (NAICS), Return on capital employed, 2000 to 2014.

8. For example, one estimate sets the irreversibility premium for projects with limited resale potential at between 1.1% and 5.1%. This premium, as well as a risk premium, is added to the rate of return on capital. At the other extreme, for projects with limited resale potential, a low depreciation rate, and a context of economic crisis, an estimate of the irreversibility premium of investment amounts to 17.4%, which would mean an opportunity cost of 24.6%, even before adding on a risk premium. Robert S. Chirinko and Huntley Schaller, “The Irreversibility Premium,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 56, No. 3, April 2009, pp. 399 and 402.

9. TD Economics, Soft Economy Set the Stage for Wider Federal Deficits, Observation, October 13, 2016, p. 2.