Tax Increases Don’t Always Mean More Money for the Government – Even on Cigarettes

Tax increases do not in each and every case lead to increases in government revenues. The "Laffer curve," named after economist Arthur Laffer, suggests that things are more complex because taxes affect the behaviour of taxpayers. When taxes on the consumption of a good are too high, you can get to a point where taxable consumption decreases and government revenues diminish rather than increase. Or at any rate, they don't increase as much as what would be expected given the tax increase. This phenomenon constrains government's ability to levy taxes.

Tobacco taxes are an interesting case in point to which Laffer just dedicated a new book, The Handbook of Tobacco Taxation: Theory and Practice, available online for free.

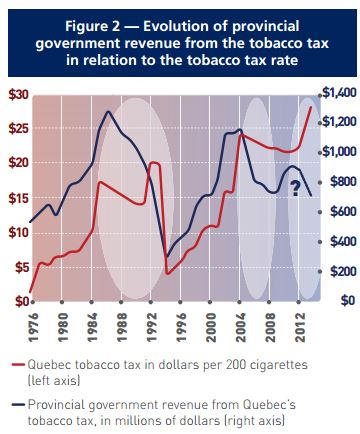

There have been numerous examples in Canada of excessive taxes having a negative impact on government revenues. As shown by my colleagues Jean-François Minardi and Francis Pouliot in a study published last January ., there's been three "Laffer moments" when it comes to tobacco tax revenues in Quebec since 1976. Whenever the level of taxation exceeded $15 per carton, the proceeds of the tobacco taxes eventually diminished.

These are no isolated incidents. Laffer shows that the theory is confirmed by the experience of Cyprus, Denmark, Germany, Great Britain, Greece, Ireland, Latvia, Portugal, and Sweden. In fact, after one federal and two provincial tax increases on tobacco products over the last two years, it would not be surprising to see another "Laffer moment" in Quebec in the near future.

It is true that smoking is a major public health concern, and one might be tempted to say that the change in behaviour is desirable, whatever the effect on government revenue. Again, Laffer tells us that things are more complicated than it seems.

While it is true that some people are deterred from smoking by tax increases, this is not the case of all smokers. Some avoid taxes by buying contraband cigarettes. Tax increases have no effect on the health of these smokers.

Smokers can also alter their behaviour by using another tobacco product. Laffer cites two studies showing that after tobacco tax increases, smokers switched to another brand of cigarettes yielding more nicotine and tar. This suggests that some Canadian smokers might offset price increases by moving from lighter kinds of cigarettes, like some slims, or menthol and mellow blends, to more potent but equally taxed equivalents. Tax increases are detrimental to these smokers' health.

Laffer's conclusion about the effectiveness of tobacco taxes at meeting public health goals is that, in an ideal world where there would be no smuggling and contraband, price increases would have a beneficial effect on the quantity of tobacco consumed, but not necessarily on the quantity of harm to smokers. In practice, where contraband does exist and plays a substantial role (27% of the Canadian tobacco market in 2008 according to a study from the Fraser Institute ), the effects on public health could be harmful.

Laffer's insights applied to the Canadian situation make it evident that taxes have already reached a level where their growth will likely bring down tax revenues, and will lead to uncertain consequences on public health. They might be very popular among politicians, but research clearly indicates that the positive effects of tobacco taxes are not as obvious, and automatic, as they may seem at first glance.

Michel Kelly-Gagnon is President and CEO of the Montreal Economic Institute. The views reflected in this column are his own.