Viewpoint – Avoiding the Aeronautics Subsidy Race Canada Is Sure to Lose

While all countries subsidize their aircraft industries at different levels, the Canadian sector has been making headlines recently. The massive help Bombardier has received sets a precedent, which other countries could exploit to justify heavily assisting their aerospace industries too, potentially creating a beggar-thy-neighbour dynamic. The scenario of a subsidy race in the aerospace industries of all countries is now a real possibility, unless there is a credible signal that such government intervention will be limited in the future.

Media release: Aeronautics: Canada must avoid a subsidy race

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| Why we need a global non-aggression pact among airliners (The Globe and Mail, August 10, 2017)

Aéronautique: un pacte de non-agression nécessaire (www.lesaffaires.com, August 3, 2017) |

Interview (in French) with Mathieu Bédard (Duhaime le midi, FM93, August 3, 2017) |

This Viewpoint was prepared by Mathieu Bédard, Economist at the MEI, in collaboration with Michel Kelly-Gagnon, President and CEO of the MEI. The MEI’s Taxation Series aims to shine a light on the fiscal policies of governments and to study their effect on economic growth and the standard of living of citizens.

While all countries subsidize their aircraft industries at different levels, the Canadian sector has been making headlines recently. The massive help Bombardier has received(1) sets a precedent, which other countries could exploit to justify heavily assisting their aerospace industries too, potentially creating a beggar-thy-neighbour dynamic.

The scenario of a subsidy race in the aerospace industries of all countries is now a real possibility, unless there is a credible signal that such government intervention will be limited in the future. Such a signal could take the form of a new international agreement, which Canada has a strong interest in initiating.

The Danger of a Subsidy Race

From an economic point of view, there are many reasons to oppose subsidies. For one thing, they represent resources that are being invested by governments based on political considerations, rather than on economic or financial ones. This means that these funds would likely be put toward more valuable uses if invested elsewhere in the economy.

Furthermore, the process of granting state aid creates a demand, whereby companies invest in their lobbying capacity rather than in their aircrafts and services. Meanwhile, taxpayers—including other companies—are forced to gamble on the success of subsidized aircrafts.

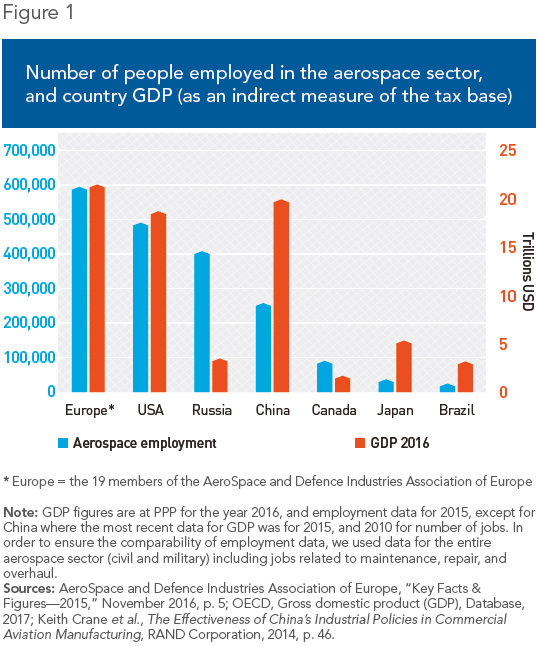

But these drawbacks pale in comparison with the ills of a subsidy race. Politicians in countries like China could take inspiration from recent Canadian government support to its industry, and use their much larger tax base to assist their aircraft sector in becoming a world leader. In a country like Russia, with a much larger workforce in the sector, and a less diversified economy as well, the stakes are higher than they are in Canada (see Figure 1).

A smaller country like Canada would never be able to hold its own in a subsidy race with such countries. The Canadian industry would wither, losing significant market share. A very large portion of the 55,724 jobs in the aerospace manufacturing industry would thus be put in danger.(2) Of course, even the “winners” of such a conflict would pay a heavy price—or at least, their taxpayers would.

The Remedy

While state aid is never a desirable thing from an economic point of view, it is a political reality. But although it may be unrealistic to call for the immediate and permanent elimination of such aid—and no other country would likely follow suit—it can nevertheless be circumscribed by international agreements.

There have been other such agreements in the past. For example, there is the Aircraft Sector Understanding (ASU), its first version signed in 1986 (then known as the LASU – Large Aircraft Sector Understanding), and updated a few times since then, with its latest major revision in 2011.(3) The ASU has been relatively effective in limiting the expansion of state aid through export credits, but governments have been creative in finding other ways to directly and indirectly subsidize their national champions.

This support can take the form of synergies between military and commercial work, funding of R&D, direct subsidies for specific aircraft projects, equity infusions, debt relief, taxation rules favouring domestic manufacturers, tax breaks, export guarantees, exchange rate guarantees, and many others.(4)

Nor would it be the first time the Canadian aeronautic sector provokes negotiations and the adoption of a new international treaty. The 2011 version of the ASU, negotiated through the OECD, was largely a response to the need to classify new Bombardier C Series planes, still in development back then, in one of the three categories of airplanes (large, regional, and business).(5)

A new version of this treaty, a kind of “ASU plus,” could provide guidelines for other types of support that governments routinely, and “exceptionally,” provide to their countries’ aircraft manufacturers. While it is beyond the scope of the present publication to detail specific clauses that such a treaty should include, it would obviously define what kind of government support is acceptable. It would also specify the maximum amount that such assistance could represent in the total cost of producing a plane without threatening the fragile international equilibrium. Finally, such an agreement should reaffirm WTO principles with regard to international trade: stability, respect for the rules, the absence of discrimination, gradually freer trade through negotiation, as well as economic development throughout the world.(6)

The benefits of such an agreement would extend beyond the participating countries. The promise that all the countries involved in the current ASU would respect it would likely be enough of a credible commitment to dissuade ASU non-signatories like Russia and China from engaging in a harmful subsidy race.

Conclusion

A new agreement between aircraft manufacturing countries could act as a non-aggression pact, and prevent a subsidy race which would have devastating effects on Canadian aircraft companies and workers. Competition, in order to be as widely beneficial as possible, should not be based on which government has the deepest pockets, but on the merits of the competing products themselves, and of the companies that provide them.

References

1. The financial assistance paid directly or indirectly to Bombardier by the Quebec and Canadian governments over the past two years totals over C$3 billion. Bombardier, “Bombardier Announces Financial Results for the Third Quarter Ended September 30, 2015 – Government of Québec Partners with Bombardier for $1 billion in C Series as Certification Nears,” Press release, October 29, 2015; Bombardier, “Bombardier and CDPQ enter into definitive agreement: CDPQ to acquire 30% of newly-created BT Holdco for $1.5 billion,” Press release, November 19, 2015; Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, “Government of Canada and Bombardier announce significant investment to strengthen leadership in aerospace,” Press release, February 7, 2017.

2. The employment figure includes the space and aeronautic sector in both civil and defence activities, but does not include jobs related to maintenance, repair, and overhaul. Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada and Aerospace Industries Association of Canada, “State of Canada’s Aerospace Industry: 2017 Report,” June 13, 2017, p. 18.

3. Jane M. Cavanaugh, “In Search of a Level Playing Field: The 2011 Aircraft Sector Understanding,” International Law Office, April 27, 2011.

4. Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung, Centre for Energy Conservation and Environmental Technology and Economic Research for the Public Sector, Financial Support to the Aviation Sector, Document prepared on behalf of Germany’s Federal Environmental Agency, June 2003, p. 21.

5. Jane M. Cavanaugh, op. cit., endnote 3. In short, the 2011 treaty eliminated the distinction between the subsidy rules for large and small planes, as there were disagreements about which category the C Series planes belonged to.

6. World Trade Organization, Understanding the WTO: Basics, Principles of the trading system.