Viewpoint – The Economic Costs of Protectionism: The Case of Softwood Lumber

Despite multiple legal setbacks before WTO and NAFTA tribunals, American softwood lumber producers are still calling for the imposition of limits and tariffs on Canadian imports, arguing that they represent unfair competition because they are subsidized. If no agreement is ratified before October 12, 2016, imports from Canada could be subject to tariffs of up to 25%. The case of softwood lumber is a good illustration of how protectionism provides benefits for a limited group, all while harming a majority.

Canadian media release: Softwood lumber dispute: Canadian producers are still losing out

American media release: Softwood lumber dispute: American consumers have lost nearly $6 billion since 2006

Links of interest

Links of interest

|

|

|

|

La crise du 2 X 4 coûte cher (Le Quotidien, September 16, 2016)

Canadian wood producers face 25 per-cent tariff in border fight (The Vancouver Sun, September 16, 2016) Bois d'œuvre : une crise qui coûte cher (Le Soleil, September 20, 2016) |

Interview (in French) with Alexandre Moreau (Au coeur du monde, Radio-Canada, September 15, 2016) |

Viewpoint – The Economic Costs of Protectionism: The Case of Softwood Lumber

Despite multiple legal setbacks before WTO and NAFTA tribunals, American softwood lumber producers are still calling for the imposition of limits and tariffs on Canadian imports, arguing that they represent unfair competition because they are subsidized.(1) If no agreement is ratified before October 12, 2016, imports from Canada could be subject to tariffs of up to 25%.(2) The case of softwood lumber is a good illustration of how protectionism provides benefits for a limited group, all while harming a majority.

Is Canadian Lumber Subsidized?

The absence of a market mechanism that is deemed appropriate for determining the level of royalties charged by the provinces is one of the main elements of the softwood lumber dispute, which has lasted for over 30 years.(3) In Canada, nearly all wood is harvested from public forests, whereas 90% of American softwood lumber comes from private forests. A NAFTA ruling indeed confirmed the existence of a subsidy for Canadian softwood lumber. However, it was below the threshold required to justify sanctions according to American law.(4) The existence of harm or the threat of harm caused to the industry has therefore never been demonstrated beyond all doubt by the American government.

Given this situation, negotiations had led to the ratification of the latest Agreement between the two countries, stretching from 2006 to 2015, which proposed two options to the provinces concerned.(5) The first was based on export charges going from 5% to 15%, while the second involved lower charges, but combined with a volume limit. The two kicked in whenever the price of softwood lumber was at or below US$355 per thousand board feet.(6) For the period covered by the Agreement, the tariffs were applied 77% of the time.(7)

The Canadian wood product manufacturing sector is highly dependent on the American market. Manufacturing sales for this sector totalled $26 billion and supported 91,781 jobs in 2015. If we take the specific case of softwood lumber targeted by the Canada-United States Agreement, the value of exports fell from $7.1 billion in 2006 to $5.6 billion in 2015. Hence, 23% of this sector’s total sales and over 21,400 jobs were directly connected to American market conditions and to the terms of the latest deal on Canadian softwood lumber.(8)

The Winners and Losers

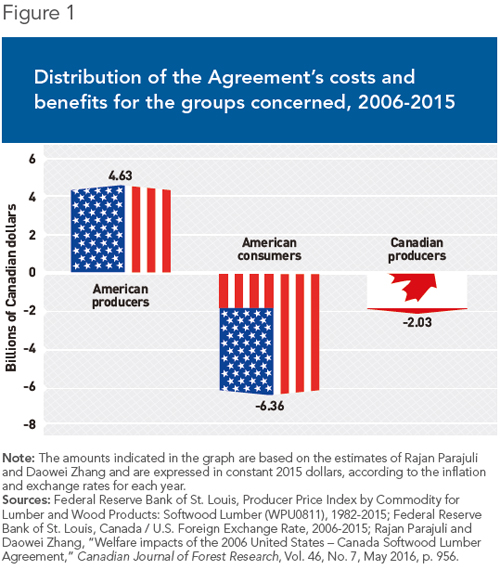

By isolating the different factors that can influence the demand for Canadian softwood lumber on the American market, it is possible to estimate the impact of the charges established in the Agreement when prices were below the defined threshold. These charges reduced Canadian exports by 7.78%,(9) which cost the Canadian forestry sector over $2 billion (see Figure 1).

Although their point of view is rarely mentioned when discussing this issue, American softwood lumber consumers are also victims of the protectionist measures put in place by the Agreement. Indeed, the lumber targeted by it is used primarily for residential construction on the American market. American consumers therefore had to get their wood from an alternative and more expensive source when the tariff barriers led to reduced Canadian imports.(10) Hence, between 2006 and 2015, they had to spend an additional C$6.36 billion.

American producers, for their part, made substantial profits thanks to the tariff barriers. Whereas the market share occupied by Canadian imports of softwood lumber fluctuated around 33% toward the end of the 1990s, it had fallen to an average of just 28% between 2006 and 2013. At the same time, the share occupied by American production increased considerably, taking up nearly all of the slack that was due to the drop in Canadian imports.(11) American producers thus registered additional net earnings of C$4.63 billion because of the restrictions imposed as a result of the 2006-2015 Agreement.

Conclusion

The softwood lumber dispute highlights a fundamental aspect of protectionism: it concentrates benefits within a limited group, whereas costs are spread over a large number of economic actors. In the case of softwood lumber, American producers have gotten richer since the start of the dispute, whereas Canadian companies and American consumers continue to pay the price.

This Viewpoint was prepared by Alexandre Moreau, Public Policy Analyst at the MEI. The MEI’s Regulation Series seeks to examine the often unintended consequences for individuals and businesses of various laws and rules, in contrast with their stated goals.

References

1. Troy Brynelson “Timber execs, Wyden call for new deal as lumber prices nosedive and industry frets,” The News-Review, August 3, 2016.

2. Christian Noël, “Vers une 5e guerre commerciale sur le bois d’œuvre?” Radio-Canada, June 6, 2016.

3. British Columbia and Quebec more recently have implemented timber auction mechanisms which allow royalty levels to be determined. BC Timber Sales, Welcome to BC Timber Sales; Bureau de mise en marché des bois, À propos du bureau de mise en marché des bois; Peter Berg, “The Canada-U.S. Softwood Lumber Dispute,” Topical Information for Parliamentarians, Library of Parliament of Canada, June 10, 2004.

4. NAFTA panel decision, November 2005. See U.S. Lumber Coalition, “U.S. – Canada Lumber Trade Dispute: A Brief History,” October 2015, p. 3.

5. Excluding the Atlantic Provinces and a few sawmills. See the Technical Annex on the MEI’s website.

6. Global Affairs Canada, The Canada-United States Softwood Lumber Agreement, July 26, 2013.

7. Rajan Parajuli and Daowei Zhang, “Welfare Impacts of the 2006 United States – Canada Softwood Lumber Agreement,” Canadian Journal of Forest Research, Vol. 46, No. 7, May 2016, p. 956.

8. This is an average for the 2006-2015 period that excludes jobs related to logging. See the Technical Annex on the MEI’s website.

9. Rajan Parajuli and Daowei Zhang, op. cit., endnote 7, p. 952.

10. Katie Hoover and Ian F. Fergusson, Softwood Lumber Imports from Canada: Current Issues, Congressional Research Service, August 27, 2015, p. 4.

11. Ibid., pp. 4 and 19.