Viewpoint – The Federal Government’s Deficits Will Not Stimulate the Canadian Economy

A number of Bay Street economists are urging the federal government to loosen its purse strings even more and run larger deficits than announced during the election campaign in order to “stimulate” the Canadian economy. This short-term perspective, however, fails to take into account several important considerations.

Media release: Deficits won’t stimulate the economy

Links of interest

Links of interest

|

|

|

| Deficit will not stimulate the economy (Toronto Sun, March 10, 2016) |

Viewpoint – The Federal Government’s Deficits Will Not Stimulate the Canadian Economy

A number of Bay Street economists are urging the federal government to loosen its purse strings even more and run larger deficits than announced during the election campaign in order to “stimulate” the Canadian economy. This short-term perspective, however, fails to take into account several important considerations.

How to Stimulate an Economy

First of all, the Keynesian macroeconomic theory upon which these economists base their recommendations suggests boosting the economy through public spending only during periods of recession. But Canada is not in a recession, nor was it in a recession in 2015, and according to the Bank of Canada’s latest forecasts, it will not be in one in 2016 either, regardless of the size of the federal deficit. In fact, the economy should experience slow but gradually accelerating growth.(1)

Second, even if we were to experience an economic downturn, it is not obvious that additional government spending would be the solution. Several Nobel Prize-winning economists believe that even in periods of recession, the government cannot boost the economy by substantially increasing its spending in such a way as to create a large deficit.(2)

Indeed, in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, it is the OECD countries that reduced both their public spending and their revenues that succeeded in achieving the fastest average annual growth. Conversely, countries that chose to increase both their spending and their tax burdens experienced very slow growth, and even economic contraction if Greece is included in the calculation.(3)

Economist Valerie A. Ramey of the University of California in San Diego reviewed the recent literature on this question. She shows that an increase in public spending does not stimulate private spending, and even has the effect of substantially reducing it in the majority of cases.(4) According to Ramey, public spending can only create jobs in the public sector, and no sustainable employment in the private sector.

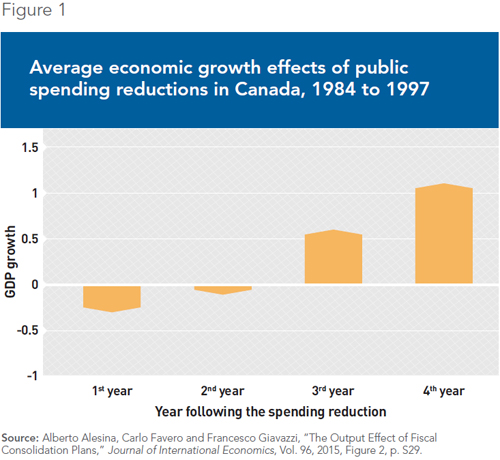

Similarly, the research recently published by António Afonso and João Tovar Jalles, respectively from the European Central Bank and the OECD, shows that when the government competes less with the private sector in the recruitment of workers and the use of capital, private investment takes over.(5) In the short term, public spending cuts have a modest negative effect on economic activity, since there is a short delay before private spending can take up the slack.(6) In the longer term, though, the positive effects on economic growth become overwhelmingly dominant.

This is also what Harvard economist Alberto Alesina and two of his colleagues found by analyzing the evolution of federal budgets from 1984 to 1997 and isolating the economic growth effects of public spending reductions as a proportion of GDP over the four years that followed(7) (see Figure 1).

Larger Deficits Mean More Taxes Sooner or Later

To all of this, supporters of a large deficit invariably reply that we need to take advantage of the fact that interest rates are currently very low. Even at low rates, however, loans have to be paid back sooner or later—and when the government is the one doing the borrowing, they have to be paid back with future taxes.

A universal result in economics, described in every introductory textbook, is that collecting a dollar of taxes costs society more than a dollar, as a general rule. Raising taxes has the effect of creating distortions in the private sector of the economy, of reducing purchasing power, and of discouraging productive activities. This is called the deadweight loss of taxation, which is to say that above a certain level, increasing taxes entails a loss of economic well-being that is larger than the growth of well-being funded by the government’s additional revenues.

Recent studies vary, with estimates of how much each tax dollar collected costs society ranging between $1.10 in the research carried out by Robert J. Barro and Chuck Redlick of Harvard,(8) and up to $5.00 in some cases according to a study by Andrew Mountford and Harald Uhlig of the Universities of London and Chicago.(9) Given that the burden of taxation on the economy must be added to the cost of reimbursing loans, these therefore end up costing our economy quite a lot, even when interest rates are very low.

Conclusion

The difficult choices which the Couillard government in Quebec has had to face in order to return to a balanced budget should serve as a warning to the federal government. Indeed, eliminating the deficit, even in periods of growth, is always a difficult exercise that invariably provokes an outcry. In other words, after a stimulus package, getting back to a balanced budget is not simply a matter of issuing a decree.

The best way to stimulate growth is to remove the obstacles keeping entrepreneurs from launching new projects and companies from putting labour and capital to work. Some good candidates include tax cuts, reducing the regulatory burden, and allowing easier access to capital markets. Increasing government spending, however, will just pull resources out of the private sector and postpone a sustainable recovery.

This Viewpoint was prepared by Mathieu Bédard, Economist at the MEI. He holds a PhD in economics from Aix-Marseille University, and a master’s degree in economic analysis of institutions from Paul Cézanne University. The MEI’s Taxation Series aims to shine a light on the fiscal policies of governments and to study their effect on economic growth and the standard of living of citizens.

References

1. Bank of Canada, Monetary Policy Report, January 2016, p. 14.

2. See “The Stimulus Rush,” Chicago Tribune, January 13, 2009; Robert E. Lucas Jr., “The death of Keynesian economics,” Issues and Ideas, Vol. 2, 1980; Eugene F. Fama, “Bailouts and Stimulus Plans,” University of Chicago, Booth School of Business, January 13, 2009; Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom, University of Chicago Press, 40th anniversary edition, 2002.

3. Mathieu Bédard, Vincent Geloso, and Youcef Msaid, “Cutting Public Spending Promotes Economic Growth,” Economic Note, MEI, October 8, 2015.

4. Valerie A. Ramey, “Government Spending and Private Activity,” in Alberto Alesina and Francesco Giavazzi (eds.), Fiscal Policy after the Financial Crisis, University of Chicago Press, June 2013, pp. 19-55.

5. Antonio Afonso and João Tovar Jalles, “Assessing Fiscal Episodes,” Economic Modelling, Vol. 37, February 2014, pp. 255-270.

6. Robert J. Barro and Charles J. Redlick, “Macroeconomic Effects from Government Purchases and Taxes,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 126, No. 1, January 2011, pp. 51-102; Lawrence Christiano, Martin Eichenbaum and Sergio Rebelo, “When Is the Government Spending Multiplier Large?” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 119, No. 1, February 2011, pp. 78-121; Price Fishback and Valentina Kachanovskaya, “The Multiplier for Federal Spending in the States During the Great Depression,” Journal of Economic History, Vol. 75, No. 1, 2015, pp. 125-162.

7. Alberto Alesina, Carlo Favero and Francesco Giavazzi, “The Output Effect of Fiscal Consolidation Plans,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 96, 2015, Figure 2, pp. S19-S42.

8. Robert J. Barro and Charles J. Redlick, “Macroeconomic Effects from Government Purchases and Taxes,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 126, No. 1, January 2011, pp. 51-102.

9. Andrew Mountford and Harald Uhlig, “What Are the Effects of Fiscal Policy Shocks?” Journal of Applied Econometrics, Vol. 24, No. 6, September 2009, pp. 960-992.